morrison-dylan-fan

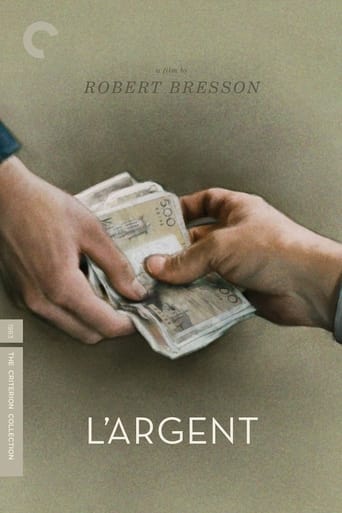

After watching a great double bill,I decided to check François Truffaut's other credits. Looking at this time for 1983 titles to view for an upcoming ICM poll,I was saddened to find that '83 was the year Truffaut made his final production. Searching for other French films from the year to view,I was surprised to find that along with Truffaut, Robert Bresson had also made his final film in 1983,which led to me paying tribute to both auteurs. View on the film:Struggling to fund the movie since he began writing the adaptation in 1977, writer/directing auteur Robert Bresson proves that it was worth the effort with a highly distinctive,minimalist appearance. Updating Leo Tolstoy's short story to the present, Bresson spirals down with Yvon Targe in icy, neural mode shots of inanimate objects and stilted glances towards the corners of rooms feeling the screen with eerie, muffled sounds, and the pushing of falling objects into frame drawing a sketch of Targe's latest unfortunate incident. While following Bresson's method of the actors being models, Christian Patey brilliantly takes advantage of this in his performance of Targe, who becomes increasingly passive to every bad turn set off from the fake note,to the point where Patey ends Targe looking off with hollow eyes. Updating Leo Tolstoy's short story, the screenplay by Bresson makes each drop Targe takes into this merciless world be turned from Targe's first fold of money.

tieman64

"They are not intrinsically evil, but their behaviour has evil consequences." - Bresson Economist Frederic Bastiat once wrote "the parable of the broken window", in which he examined the economic implications of a boy breaking a shopkeeper's window in a fictional town. After the window's destruction, so the parable goes, the townspeople then observe that the shopkeeper will need to pay a local glass-maker to fix his window, that the glass-maker might in turn spend these earnings at a bakery, that the baker would then spend this profit elsewhere, and so on. Therefore, the townspeople conclude, the broken window turns out to be not a loss, but rather a stimulus that starts an unending ripple effect of new economic activity. Rather than a problem, the boy's act of destruction seems to be a way to give the economy of the fictional town a boost.Bastiat's point, however, is that whilst this "stimulus" is easily observed, there is a corresponding absence of spending, along with motions elsewhere within the system which go on unseen. For example, forced to spend his savings on a replacement window, the hapless shopkeeper is now unable to pay for other things, like a new display case or shelves. The expense of buying a window is thereby a silent, unseen loss of potential business expansion. So while the glass-maker may benefit from the increased business in the short term, it has come at the expense of others. Overall, the total wealth in the economy has been decreased by the cost of a window.Indeed, if wealth could somehow be increased by breaking windows, why not break every window in sight? If a glass-maker's increased business constitutes economic gain, why not destroy the entire town so that the whole population could be put to work rebuilding everything? Despite the resulting "full employment", this scenario would represent an enormous and senseless destruction of wealth. Though of course such wanton destruction is sometimes the aim; war loves profiting off destruction, and destructive cycles are often precisely what keeps our economic systems afloat.Regardless, Bastiat's parable relates to our current economic crisis (the late 2000 financial crisis and subsequent measures, bailouts and tax breaks) in other ways. If governments can benefit economies by paying off the debts of a few, why not pay off the debts of all? Why not take on the mortgages and credit card debts of entire countries? Bastiat's answer (which even basic physics told us centuries ago): spending money creates no wealth and aggregate debt must perpetually increase. The "economic activity" we see as a result of government spending is but the transfer of wealth from here to there. Indeed, when the overhead of government bureaucracy is taken into account (and the fact that the government lends its money at zero and is then forced to buy it back at 3 or 4 percent, along with the contradictions of interest-based/issued money) it actually results in a long term loss; an entropy effect if you will. Today governments are unveiling a slew of stimulus packages which are based on the premise, or wager, that the economy can be renewed and led to wealth creation. But while such "stimulated" financial health may seem obvious or desired in the short term, it always comes at a higher cost down the road; deeper holes to fall into and future bondage.Robert Bresson's final two films, "The Devil Probably" and "Money", are implicitly about hidden costs and the invisible currents of our economy, though Bresson is more concerned with how such things intersect with issues of spirituality, personal autonomy and existentialism. In this regard, "the Devil" of "The Devil Probably" alluded to "invisible market forces" which "influence everything". Struggling to concoct a means of ethically living within such an all-pervasive system, our hero thus opts to commit suicide, Bresson finding a certain spirituality in his hero's revocation of the material. "Money", however, presents the flip-side of "Devil": the grotesque toll living within the system has on the soul, spirit and body. Note that by this point Bresson was fully atheist. His conceptions of "soul" and "spirituality" are here more akin to a code of ethics.The plot: the son of wealthy parents is in debt. He counterfeits 500 dollars - think of him as a central bank, printing money when it suits him - and knowingly passes this money onto a photography shop, who just as knowingly passes the money to Yvon, an oil delivery man. Yvon attempts to use this counterfeit money at a restaurant, but is arrested because the proprietors have no faith in him and his money. The word credit itself comes from the Latin word "credere", "to believe", the system as a whole fuelled by a kind of irrational faith.Yvon then quickly descends into life of crime, before meeting a woman who offers him redemption. He murders her for cash instead and then guiltily turns himself over to the police. Like "The Devil Probably", money, labelled the new divine by everyone in the film, is seen to have a life of its own, controlling everyone and everything in society. As it circulates, humans impassively disadvantaged fellow humans, whilst the wealthy use their power to escape both the law and such "trickle down" disadvantages. In the impersonal detachment of contemporary society, money serves as the surrogate for human emotions, which are frivolously expressed through its casual exchange. But money also exhibits a near biological behaviour: virulent and infectious, the notes contaminate everyone who comes into contact with them, sins escalating, snowballing and slowly destroying souls. Yvon himself struggles to summon the will necessary to escape money's grip and the futures it foreordains. He is forever held in its sway. The film's narrative trajectory is literally from a ATM machine's mouth to perpetual confinement. It's a reverse of "Probably's" suicide: slow, pitiful and ignoble.7.9/10 – Multiple viewings required.

kai ringler

when i seen this the other nite on IFC i wasn't quite sure what to make of it, it's definitely a little confusing, but in another sort of way very complicated and interesting. no big stars in this being it's independent which i feel is good because it would have taken away from the movie in general i feel, to the movie it's about what happens when a fake 500 french franc is passed from one person to another.. instead of just eating the note and writing it off, a man proceeds to try to pass it off to the next person setting off a chain of events that sends our main character into a tailspin of events to come. he spins out of control and doing some things that he probably wouldn't normally do,, but since he felt that he was wronged in having the bill passed to him, he figured , well let me get rid of it, overall i think that this is a tigh film worth watching.