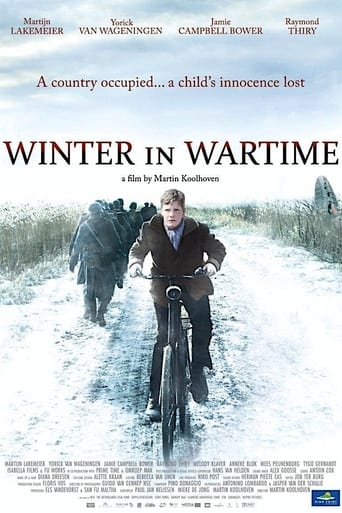

jandesimpson

What to do during a week of long evenings when my DVD player was on the blink? Fortunately a judicious bit of web surfing provided quite a rewarding answer - a channel offering free viewing of several hundred films. Many looked pretty dire so I whittled it down to the "World Cinema" genre. What rapture! De Sica's "Shoeshine", which I had not seen since I was a teenager, was there. For a second choice I thought I would try something completely unknown. I suppose it was the title "Winter in Wartime" that made this my next selection. It just sounded so evocative and atmospheric. As far as expectations of time and place were concerned the film certainly did not disappoint. The Netherlands under German occupation during the last winter of the second world war was deep in snow. We were viewing icy landscapes full of danger and unease through the eyes of a young teenage boy who was about to have his natural instincts of right and wrong severely tested by being in that place and time. Perhaps what I most liked about the film was that, is spite of being so realistic in its depiction of a particularly ugly period of history, it had those very elements of a good "Boys' Own" yarn that reminded me of stories I had not read for years - youngster and shot-down British airman playing a sort of scouts' "wide game" with the Nazis in frozen woodlands. Towards the end it became a real page turner. And then just when you thought you knew how it would all turn out, there was a real volte-face when a supposed goodie turned out to be the arch baddie of the piece. Never mind that the film often strained credulity, particularly when the airman with such a gammy leg performed acts of gymnastic dexterity. It was all such fun, except that it wasn't really. How could it when we had just witnessed an act of Nazi reprisal of such savage barbarity? Those old "Boys' Own" yarns were never as hard edged as this, making for a mixture of genres that instilled a real sense of unease.

JackCerf

The Dutch had an ambivalent World War II experience, and movies like this one, Black Book, and Soldier of Orange reflect it. The Germans considered them junior Aryans and behaved "correctly" for the most part. There were a fair number of Dutch collaborators. The bureaucracy cooperated, and a much higher percentage of Jews got rounded up in Holland than in Belgium or France. If you weren't a Jew, weren't drafted to work in Germany, and kept your mouth shut, life went on pretty much normally until the Hunger Winter of 44-45, when food and fuel supplies dried up and things got very hard. The Dutch resistance movement was a fiasco; German military intelligence infiltrated, captured and doubled the agents the British parachuted in, and sent a steady stream of false messages to London. Because Holland was off the main Allied route into Germany, most of it wasn't liberated until weeks or days before the end of the war. Their movies tend to present the Dutch experience as mostly civilized middle class people trying to get by, making moral compromises, and not being very good at anything more belligerent or heroic. The center of Winter in Wartime is Mikiel, a 13 year old in rural Overijssel province. His village is a backwater where the German checkpoint at the ferry marches off for a tea break at 3 p.m. every day, allowing people without papers to sneak across. The garrison commander is a fat, overage Captain, and his troops are boys barely out of high school. Mikiel's family are well to do, and his father is the mayor. One of their neighbors is apparently member of the NSB, the Dutch Nazi party. Mikiel is a typical boy of his age: active, curious, and just at the point where his interest is beginning to shift from model airplanes to girls. He zips around on his bike, dodges chores, teases his older sister the nurse, loves the family's riding horse, is fascinated by anything to do with the war and loathes the Germans. With all the moral certainty of a 13 year old, he detests his father, who must deal with them every day. He idolizes his cool bachelor Uncle Ben, who has a beard, a twinkle in his eye, no apparent occupation and something to do with the resistance. We meet Mikiel when he gets into some minor trouble; he's caught when he and his friend try to loot souvenirs from a newly crashed British bomber in the woods, and the German garrison commander releases him to his father. Because he's a boy and the mayor's son, he moves around untouched and unsuspected, so his best friend's older brother, who is involved in the resistance, gives him a message to carry. When the brother is captured and the intended recipient is killed resisting arrest, Mikiel opens the letter, follows it, and finds a British airman from the bomber being hidden in a dugout in the woods with a wounded leg. Jack, the airman, needs to get to a town where he's been told he'll find an escape contact.Mikiel decides that he's going to take care of this all by himself; he'll bring two bikes and some civilian clothes, and when Jack is ready to travel in a few days they'll cross the ferry during the guards' tea break. In the meantime, he'll bring Jack food, hang out, do a little hero worshiping, enjoy his adventure, and feel like he's helping to win the war. But what can go wrong does. The wound gets infected, Jack is too feverish to travel, and Mikiel has to bring his sister out to the woods and let her in on the secret. Within a few days, he finds himself in a very different movie than the one playing in his head -- he's now the Kid Brother in the picture about the Gallant British Pilot and the Pretty Dutch Nurse. He doesn't fully grasp what's going on, but he knows he's got a rival for Jack's attention, and he doesn't like it one bit. So he redoubles his efforts to make himself indispensable. Then things go even more wrong. There's a dead German out in the woods -- Jack had to shoot him to escape capture. The Germans find the body and take civilian hostages to shoot in retaliation for what they think is resistance activity. Mikiel finally realizes he's in over is head and calls in Uncle Ben.There are plenty of exciting narrow scrapes and close calls, not all of which end well. Without giving anything away, I can say that Mikiel's father, his uncle, the pro-Nazi neighbor and the boy himself all turn out to have various qualities that he hasn't imagined. He loses a great deal, including his boyhood illusions, and when the day of liberation arrives he knows a lot more about life but doesn't feel much like celebrating. The peculiarly Dutch irony is that none of it was necessary. The war was almost over, Jack would have been a POW under the Geneva Convention, the liberators would get there sooner or later, and there was no reason for anyone to have stuck their neck out.Every scene is from Mikiel's viewpoint. We see and hear only what he does, although we know a great deal more, both from historical hindsight and from adulthood. Unlike the similarly constructed Boy In Striped Pajamas, though, the script doesn't bludgeon us over the head. It sticks (with a few glitches) to the probable, and it trusts the audience to fill in what Mikiel is thinking and feeling from our own knowledge of life and of history. An American audience unfamiliar with the Dutch World War II experience will miss a good deal, and I'm sure I don't even know what fine points I might have missed. Definitely worth the two hours, though.