ReaderKenka

Let's be realistic.

Huievest

Instead, you get a movie that's enjoyable enough, but leaves you feeling like it could have been much, much more.

Allison Davies

The film never slows down or bores, plunging from one harrowing sequence to the next.

Quiet Muffin

This movie tries so hard to be funny, yet it falls flat every time. Just another example of recycled ideas repackaged with women in an attempt to appeal to a certain audience.

theskulI42

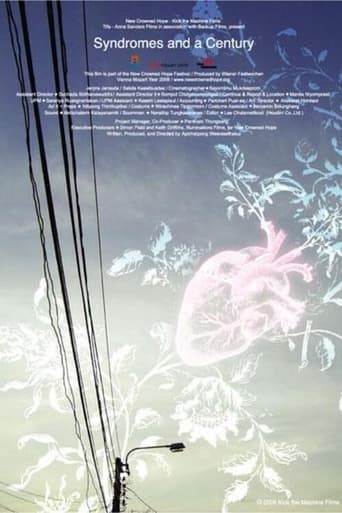

"Normally I sing about teeth and gums, but this album is all love songs" With Syndromes & a Century, Apichatpong Weeresethakul sorta-makes his own version of Tarkovsky's Mirror: a fractured, beautiful, cyclical autobiography in cinema. But Tarkovsky's film was concerned with the whole: inward-facing, but dealing with lost innocence, a desperate search for God and the scope of human existence. Early in on his film, Weeresethakul seems much more interested in the part, the details, the specifics, the ground-level, the things you won't notice unless you stop, look and listen.From the very first shot, the warm, sensual atmosphere present throughout Tropical Malady is all around us again: the weather is impossibly pristine, the sun is shining, the trees are blowing in the breeze, and everyone is speaking in rich, hushed tones. The fact that this section of the film is mined from the mind of the director's childhood at his parents' practice jibes perfectly with what we see on screen: there's a gentle, nostalgic perfection to these scenes; I'm sure this is how every day is when he thinks back, and the camera, like a child, has a tangible presence in the frequent "adult" discussions, but is generally ignored by the subjects of the gaze as a non-entity. It's as if the young Apichatpong had a camera, and now he's looking part at the conversations he witnessed but didn't understand at the time, filtered through the sweet vibe he gets when he looks back.The other unexpected thing apparent right off the bat is how amusing the film is. Weeresethakul is secretly, quite possibly, the most approachable "arthouse" director out there, and one of the initial scenes involves the ostensible lead actress Dr. Toey (Nantarat Sawaddikul) meeting with a chatty monk who relates to her his fear that he has bad chicken-based karma because it comprises a large part of his diet and dreams of breaking chicken's legs, and then tries to hustle her for pain pills. Additionally, the ostensible male lead, Dr. Ple (Arkanae Cherkam) is a dentist-cum-amateur-country-singer, and one of the monks confesses during a cleaning that he once had aspirations to be a DJ and/or comic book store owner (Ple provides the quote at the top) The second half of the film shifts to the present day, transposing the same characters to a stifling, antiseptic modern hospital, and showing the same interactions from a contemporary standpoint: the opening interview between Toey and cheerful medic Dr. Nohng (Jaruchai Iamaram) is much more curt and nitpicky. The monk is advised to cut back on the chicken not because of bad karma, but bad cholesterol, and the brusque doctor immediately attempts to prescribe medication for the monk's "panic disorder". Meanwhile, the dentist and the younger monk's friendly interaction with the sun shining out the window has been replaced by rows of gleaming plastic machinery and absolute silence (to the point that most of the monk's face is covered in an almost-Cronenbergian hood), with the only conversation involved being instructions to open or close the mouth.It becomes quickly apparently that Weeresethakul's picture steers much closer to Tarkovsky than previously anticipated. Drifting into peer Tsai Ming-Liang's wheelhouse, his topic of conversation has become urban alienation; the subsequent loss of spirituality comes a loss of humanity. The key sequence comes around here, when the film cuts between achingly lonesome pans of religious statues neglected in small patches of urban foliage, and Dr. Nohng, on his lunch break, walking with a colleague discussing ringtones and leering at co-eds. The rest of the film runs in this vein: an older female doctor pulls liquor out of a prosthetic leg in preparation for an upcoming television appearance; a chakra healing attempt is angrily swatted away by a young patient who has a large tattoo on his neck and no desire to go to school; an intimate moment between Nohng and his significant other turns into a request for him to move with her to an ugly, high-tech "modern" area of town, and a vulgar gawk at his erection; culminating in a breathtaking sensory overload in the final sequence, wrapping up with a gloriously audacious, discordant series of shots that puts his theme in vivid focus.Social impatience, emotional disconnect, moral malfeasance, all are present in Weeresethakul's view of the present world, but he has done more than scream at the kids to get off his lawn, he's created a treatise on the state of the world: caring is in decline, kindness is in decline, focus is in decline, soul is in decline. I usually roll my eyes when a pundit begins rambling about the "good ol' days", but as a filmmaker, Weeresethakul is tasked with creating his own world, letting us share it, and making us believe it, and with Syndromes & a Century, he's presented us with the trappings of a very familiar modern world, and a hope, a wish, a prayer that maybe, just maybe, by journeying back to his childhood, if not our own, we could carve out a blueprint for how to be a little closer, a little kinder, a little wiser, towards our fellow man.--Grade: 9.5/10 (A)--

Cliff Sloane

I have now seen three of Apichatpong's films (Mysterious Objects, Blissfully Yours and now this). It finally occurred to me what is going on and why so many people, already enamored of offbeat, experimental and artsy films, still find his work difficult.I really got into "Mysterious Objects" at first, the "exquisite corpse" method and the way a simple story got embellished as he went along. But Apichatpong seemed to lose interest in the narrative, so the film became a static slide show of his travels, losing all of its narrative energy."Sud Saneha" (Blissfully Yours) never got me engaged. It was an agonizing experience in lost opportunity and self-indulgent amateurism.So now, I can say that "Syndromes and a Century" is by far the best of the three. I gave it 6 out of 10.I finally understood that Apichatpong is an artist of still images. He has no idea what to do with emotions or the people who feel them. He just allows them to populate his canvas, and pays no attention to what they do. In fact, if they do nothing and stay still, that's even better.The camera moves from time to time, but that is clearly just giving better depth to his still images. He has no skills in using images that move, other than to take them in in a decidedly passive way. There are times in this movie when it is effective (the steam entering the pipe, for example), but most of the time, it underscores his discomfort with the moving image.I really want to like his films, mostly because here in Thailand, popular culture is so crushing and stifling, anything artistic is like drops of water in a desert. But I can only cut so much slack.

Howard Schumann

Funded by the city of Vienna as part of the celebration marking the 250th anniversary of Mozart's birth, Syndromes and a Century by Thai director Apichatpong Weerasethakul (Blissfully Yours, Tropical Malady), is a visionary masterpiece that blurs the boundaries of past and present and, like the plays of Harold Pinter, explores the subjectivity of memory. It is an abstract but a very warm and often very funny film about the director's recollections of his parents, both doctors, before they fell in love. According to Apichatpong, however, it is not about biography but about emotion. "It's a film about heart", he says, "about feelings that have been forever etched in the heart." Structured in two parts similar to Tropical Malady, the opening sequence takes place in a rural hospital surrounded by lush vegetation. A woman doctor, Dr. Toey (Nantarat Sawaddikul) interviews Dr. Nohng (Jaruchai Iamaram), an ex-army medic who wants to work in the hospital, the two characters reflecting the director's parents. The questions, quite playfully, are not only about his knowledge and experience but also about his hobbies, his pets, and whether he prefers circles, squares or triangles. When asked what DDT (Dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane) stands for, he replies, "Destroy Dirty Things".Like the fragmented recollection of a dream, the film is composed of snippets of memory that start suddenly then end abruptly without resolution. A dentist wants to become a singer and takes an interest in one of his patients, a Buddhist monk whose dream is to become a disc jockey. A fellow doctor awkwardly proclaims his desperate love for Dr. Toey who relates to him a story about an infatuation that she had with an orchid expert who invited her to his farm. A woman doctor hides a pint of liquor inside a prosthetic limb. A monk tells the doctor of some bad dreams he has been having about chickens. A young patient with carbon monoxide poisoning bats tennis balls down a long hospital corridor.Syndromes and a Century does not yield to immediate deciphering as it moves swiftly from the real to the surreal and back again. Halfway through the film, the same characters repeat the opening sequence but this time it is in a modern high-tech facility and the mood is changed as well as the camera focus. The second variation is less intimate than the first, but there are no overarching judgments about past or present, rural or urban, ancient or modern. Things are exactly the way that they are and the way they are not, and we are left to embrace it all. Towards the end, a funnel inhales smoke for several minutes as if memories are being sucked into a vortex to be stored forever or forgotten. Like this serenely magical film, it casts a spell that is both hypnotic and enigmatic.

Chris Knipp

More for the strictly art-house audience than his previous Tropical Malady, the young Thai auteur's latest is an impressionistic and disorienting series of scenes centering around several different hospitals, and focused on couples, romance, job interviews, and patients. There's a singing dentist who serenades a young Buddhist monk in saffron robe whose teeth he's working on. Later the dentist-songwriter is seen performing for an audience on a fairground stage. A sequence where a potential employee or medical school candidate and an older Buddhist monk are both interviewed by a young woman doctor is repeated in the film's second half, with different camera angles and variations in the dialogue and the tone of the scenes. The film is split down the middle, though not as distinctly as in Weerasethakul's two earlier films. The gentle dental work scene where doctor and patient share their dreams and passions is repeated, only this time the leafy trees and sunshine outside are replaced by a chilling white environment, a woman assistant is present, and no one speaks. Outdoor shots focus on wide country and city spaces, and on leafy trees seen from below with sky beyond. A young man who may have brain damage from carbon monoxide poisoning swats a tennis ball down a hospital corridor. The young man who wants to become a doctor now is one, in white coat, and stares sadly into space in a long static shot. An older woman doctor hides a bottle of whisky in a prosthetic leg and drinks to relax before her weekly appearance on public television. People talk inconclusively of reincarnation. There's a visit to an orchid grower, who buys an orchid from a hospital grounds, and is visited by a woman doctor in his study after he's hung the orchid outside. All this would be annoying and disquieting were the scenes not so gentle, subtle, and evocative. Weerasethakul is an original, no doubt about that. His weddings of image and sound are sometimes numbing, sometimes subtle and enchanting, and always cryptic.Very good -- as my Beowulf teacher, who happened to be Jean Renoir's son, used to say after a passage of Old English was read -- and what does it mean? There's no simple answer to that. These are reminiscences, we're told (though not in the film itself), of the director's parents, both of them doctors; of their courtship; and of what it was like for him to grow up in the environs of a hospital. Weerasetahakul says that the first half, with its warmer, gentler mood, is for his mother, and the second, where scenes are repeated in brisker and cooler variations and the hospital is an antiseptic urban one, is for his father. Weerasethakul is a bold stylist and a confident setter of moods. But there's not a lot to put together into a narrative, just a scattered set of observations. It's a little bit as if you were watching Koyaanisqatsi, Powaqqatsi and Naqoyqatsi with tiny dialogue scenes.The film lingers on long shots of exteriors, and glides back and forth in front of a large white Buddha. It returns to a room where prostheses are made and fitted to patients and finds the room filled with smoke (could it be the carbon dioxide the young man suffers from?) which is slowly sucked out by a large funneled pipe, while ominous mechanical music throbs in the background. Don't worry about spoilers here. The ending, a large outdoor aerobics class, concludes and reveals nothing. Syndromes and a Century never unlocks its mysteries, it just casts its spell and departs with a blacked-out screen.