YouHeart

I gave it a 7.5 out of 10

Calum Hutton

It's a good bad... and worth a popcorn matinée. While it's easy to lament what could have been...

Matylda Swan

It is a whirlwind of delight --- attractive actors, stunning couture, spectacular sets and outrageous parties.

Beulah Bram

A film of deceptively outspoken contemporary relevance, this is cinema at its most alert, alarming and alive.

OttoVonB

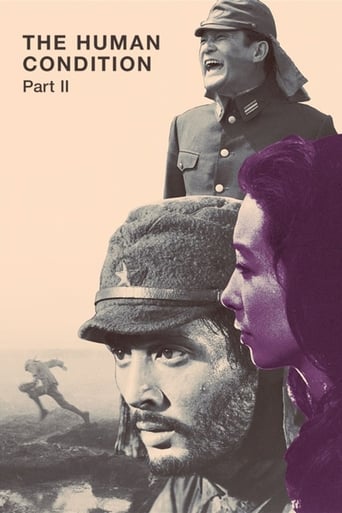

Part II of Masaki Kobayashi's "Human Condition" follows the noble Kaji (Tatsuya Nakadai), now forced into military service, as he tries to hold on to his conscience despite increasingly absurd circumstances.If Part I was a POW drama with a love story sub-plot, influencing many that followed it, then Part II is one of the best and rawest of the original boot-camp films, planting seeds for, in particular, "Full Metal Jacket". In fact, Kaji's training with the Imperial Army makes US Boot Camp look like daycare, uninclined as director Kobayashi is to pull punches when it comes to the ritual sadism of the Japanese military, which he personally endured in real life. The film bravely confronts Kaji's attitude, an almost holier-than-thou morality than annoys bullying veterans. This forces Kaji to deeply transform as a character and as a human being, from preppy moralist to actual, worn hero, a transition Nakadai pulls off with tremendous effect and efficiency.But back to the bigger picture. Like Kubrick's similar – and, one should point out, lesser – film of the same genre, this is two pictures in one: a boot-camp film about the dehumanization of the military, and a war film. The first two thirds are all intensive training, with bullying veterans and hapless recruits. Here Kaji faces an interesting contradiction: he rejects the war with all his heart, yet he has it in him to be a perfect warrior. There is the inevitable inept recruit pushed to the brink subplot, but it is handled with more humanity and sense of absurdity than most other similar films could dream of.Finally, the film takes us to the front, where all the bluster and empty honor fades in front of a line of charging enemy tanks, a startlingly effective battle scene that separates the men from the boys, though not in ways they had anticipated. Kobayashi's film rejects the traditional "bridge syndrome" typical of middle installments in film trilogies, and gives us the perfect Part II: a self-contained enough story with enough substance and depth to stand on its own, while drawing from its predecessor and opening up interesting possibilities for the finale.Roll on part III.

MartinHafer

This is the second of three films that make up "The Human Condition" trilogy. The extremely long films are based on an extremely long set of novels (in six volumes) by Jumpei Gomikawa. The books are about the journey of a man named Kaji who is simply born at the wrong time and place. His ideas about the worth of the individual and the humanity of mankind fly in opposition to the militarism of WWII-era Japan. And, not surprisingly they get him in lots of trouble. In the first film, he's assigned to be the production manager at a mine that is worked by prisoners--and the people in charge couldn't care less about how many of them they kill in the process. But Kaji's humanistic ideals are put into action instead and at first they are very successful. But the military men hate him and when he stumbles, they attack him like wolves.Here in part II, Kaji's been drafted and sent to basic training. He's seen as a trouble-maker because of his experience at the labor camp, but Kaji is a great soldier. And, unlike the average soldier in the company, he cares about the individual. So, when recruit Obara is beaten and humiliated, Kaji is the only one who sticks up for the guy--although with only one man supporting him and the rest tormenting him, what happens next isn't at all surprising--Obara kills himself. The soldiers in the unit are actually pretty happy about this--Obara was a weakling. But Kaji refuses to back down and fights his superiors, as he is fighting for what is right--and brutalizing and disregarding a weak individual is wrong.Later, Kaji manages to be promoted and he's placed in charge of a group of older recruits (as the war is going badly, they began bringing up less and less fit men to serve). He refuses to brutalize his men and the leaders of the older veterans beat Kaji up regularly. He refuses to fight back--sort of like Gandhi. Again and again he's beaten and again and again he does nothing. And, he tries to protect his men as much as he can.Later, when the war is all but over, Kaji is sent along with other ill-prepared men to meet the Russian army and their tanks. And, after this slaughter occurs, the movie ends...and Kaji is left alive on the battlefield.Much of the film seemed to be a criticism on the pointlessly brutal system where underlings were beaten for no reason whatsoever by their immediate superiors. The officers did nothing to change this and Kaji still refuses to bend to this insane situation. Instead of training focusing on teamwork and camaraderie, it's based on destroying the weak and empowering the amoral. All in all, a depressing but well made indictment on the Japanese militaristic mentality of the day. If you are looking for a similar sort of film, try finding "Fire on the Plains" (also 1959) or "The Burmese Harp" (1956). Well worth seeing.

MisterWhiplash

The Human Condition isn't an easy trilogy; it offers up tons of questions that even today have extreme relevance, particularly about man's duty to himself, to love and family, to country, to affiliation by an Emperor or Dictator, and what it is that's so insane about men in the staggering pit of hell known as war. As one can see in the second installment, The Road to Eternity, even what should be simple in a conventional war movie is turned just a bit to see the ugliness underneath. The first half of the film is Kaji, the trilogy's protagonist, in basic training and witness to more brutality towards the weak Obara (very well cast Kunie Tanaka) who commits suicide following a string of humiliations that are like Private Pyle squared Japan WW2, and how Kaji comes to grips with being a very good, disciplined soldier- the likes of which the army wants to control as they promote him- and, crucially, his last night spent with his wife Machiko (very tender performance from Aratama).The second half is Kaji off on the front lines, leading up to a big, climactic battle between Soviet and Japanese forces, which is a total horror. Although Kobayashi only goes so far to make these battle scenes dynamic (that is compared to today's battle scenes, which have far more money and just a smidgen more gore to work with), it's overall another incredible accomplishment, as story and character matter always more-so than grandiose visuals or pomposity. We see Kaji going through another level of change, as he's stripped of his "exemption" status and is now just another grunt in this rigidly regimented military, and where, as is expected but no less mortifying, the Japanese see no sign of victory despite all signs pointing otherwise.As in the first film, Kobayashi delivers moments of beauty, almost at times without trying. I absolutely was floored when the prairie fire scene turned into a desperate chase between Kaji and an escaping Shinjo, where what could have been a basic chase incorporated the fire and smoke and mud-piles into something else entirely. Or, indeed, little moments that suddenly make one's mouth agape, such as the freak-out from a soldier in the midst of the battle foaming at the mouth. If a few scenes might appear to be of the conventional sort (at least as much as Kobayashi would ever allow in this iconoclast approach), they're off-set by the wonderful performances, not least of which by Nakadai. Again he gives it his all, and matures just a little more, and displays a kind of bridge that Kaji is on between the kind-hearted but firm ways of No Greater Love and the, dare I say it, near bad-ass persona in Soldier's Prayer.It's another great entry in an impeccable trilogy, if maybe not quite as awe-inspiring as the final film.

ekeby

I've commented on parts I and III, so will comment again here, even though having just seen all three it is hard for me to separate one from the other. All three are superb, essentially telling the beginning, middle, and end of a story.I'll repeat a caution here: don't read the DVD box or too many (if any) reviews for fear of spoilers. This is one cinema experience you don't want to spoil.The movies must be seen in order, but not necessarily at one sitting. I split my viewing into different weeks and I don't think doing so diluted my experience.What you need to know is this trilogy is one of the greatest achievements in cinema of all time. Every aspect of it, almost relentlessly, is as perfect as film gets. The storyline--if such an ordinary word can be applied here--cannot be called anything other than tragic. I'll repeat what I said in my review of part III; while there are some moments of great tenderness, there is no humor at all. It is a drama in every sense of the word. Knowing something of the subject, I was somewhat reluctant to watch the series, fearing it would be too much of a downer. It's a depressing subject, yes, but it's great art. Great art is uplifting.