Plustown

A lot of perfectly good film show their cards early, establish a unique premise and let the audience explore a topic at a leisurely pace, without much in terms of surprise. this film is not one of those films.

Melanie Bouvet

The movie's not perfect, but it sticks the landing of its message. It was engaging - thrilling at times - and I personally thought it was a great time.

Neive Bellamy

Excellent and certainly provocative... If nothing else, the film is a real conversation starter.

Phillipa

Strong acting helps the film overcome an uncertain premise and create characters that hold our attention absolutely.

Marcin Kukuczka

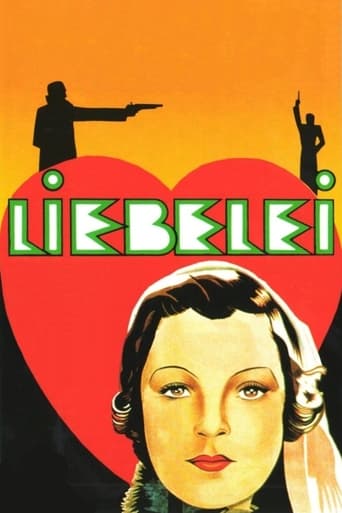

At the beginning, let me refer to my school memories. I remember discussions with my teacher of literature about the core of romanticism: its Utopian ideals and its Human perceptions. I had considered it as a purely literary abstraction until I saw this classical representative of romanticism in European cinema.The noteworthy story by Arthur Schnitzler could not see a better moment for its screen adaptation than the early 1930s, the period which saw the emergence of sound. Moreover, films could still avoid the propaganda mechanisms and requirements of censorship that were slowly approaching. No doubt this time saw some unforgettable movie productions of sensitively handled romance with exceptional artistry. Meanwhile, truly great talents had a chance to emerge. All seemed to be new, young, inexperienced, genuine and captivating...something that the storyline so nicely executes here. In fact, isn't that 'freshness' what the romantic content is all about?However, the content of LIEBELEI may occur to us quite predictable nowadays and surely does not, in itself, contribute to the top strengths of the movie. Duality of feelings, short happiness and inevitable sorrow, dramatic decisions, harshness of duels, 'misplaced honor' (as many reviewers put it) occur quite a prefabricated stuff that may as well fail to appeal to many viewers now. What requires particular attention in LIEBELEI is the manner everything is executed.Scenes of exceptional charm contribute to the movie's vital representation of 'artistic collaboration' between producers' creativity and viewers' perceptions. Although the entire movie is filled with beautiful visual imagery, these few that need a special mention are: Christine/Fritz's idyllic sleigh ride when their love seems to be as white as snow; opera sequence with no 'coincidence' of falling binoculars; Christine/Fritz's walk through the streets of Vienna; the waltz Fritz dances FIRST with Christine and THEN ... with the Baroness. The use of mirrors nicely highlights the undertone of duality. However, the film no longer resembles many 'silent' features and, we can say proudly: It has stood a test of time because it is PURELY a developed talkie. Why? Max Ophuels, as a rather unknown director at that time (LIEBELEI was his fifth feature) does not imply any characteristic style pursued but occurs to be fresh in the medium experimenting with directorial possibilities and methods at hand in 1933. This 'rich simplicity,' as well as 'emotional puzzle' and 'expressive use of the dialog' (with reference to Jesus Cortes's review) seem to take over at multiple levels and, consequently, appeal to us in a powerful manner. The cameraman Franz Planer proves his skills in some technically flawless camera movements, just to note a significant shot of Fritz and the Baron while the former one leaves the mansion in secret and the latter one comes there with suspicion. Among other crew, Theo Mackeben nicely contributes to the film's atmosphere. Thanks to music, both the tunes of waltzes and the classical pieces by Mozart and Beethoven, we may feel the charm of the early 20th century Vienna when the monarchy was still in its pinnacle. The use of classical music: some doubts may arise with Beethoven's 5th symphony in the emotionally climactic moment as a bit disturbing. Depends on how you perceive it. But where the truly memorable impact of this movie lies is in the acting.Two couples in the lead, seemingly, but only one person who stands out and steals the attention. That is MAGDA SCHNEIDER, Romy's mother in her youth (mind you it is 1933 when she was still not married to Wolf Albach-Retty). Many viewers know her from her mature age on the screen in the color 'Heimatfilme.' Also for them, her role in LIEBELEI will be extremely surprising. If someone sees the film entirely for the sake of Magda Schneider, she/he will not be disappointed. The whole spectrum of her abilities lies in portraying the rather naive but very genuine and honest character whose ideal state of life is love (a purely romantic character). In the beautiful scene, she says to her beloved Fritz about being content with whatever happens - she found love and that makes for all happiness. In the extraordinary finale sequence with the over-long close-up, Ms Schneider proves an extraordinary talent depicting all feelings, from confusion, shock, disbelief, fear to unimaginable grief. The camera is placed in such a way that we see her like the people who come with bad tidings. The moment is a masterpiece. But Miss Schneider does not only act in LIEBELEI…she also sings a folk song "Schwesterlein" which expresses enthusiasm with nostalgia hidden in the inner life? OTHER CAST: Wolfgang Liebeneiner is adequate but not outstanding as Fritz…his duality is constantly highlighted, he is not very believable in the scenes with Christine because there is another reality that exists in his life… Mr Liebeneiner is most memorable when he visits Christine's house to say 'goodbye' and she is not there. What emerges from his acting is realizing a sad fact. He really opens his eyes to what situation he has found himself in, he has placed himself in. Luise Ullrich and Carl Esmond depict the contrary couple with less romantic feelings, perhaps, but more stable future. This is particularly visible in Mizzi's character (Ullrich) contrasted to Christine's: romantic versus rational. Among the supporting cast, a mention must be made of Paul Hoerbiger, Gustaf Gruendgens and Olga Tschechowa who supply the movie with the feeling of promising days in Austrian cinema. An outstanding production and unique in its medium is clearly more Magda Schneider's artistic victory than Max Ophuels's. Much later, remade as CHRISTINE with Romy Schneider, the story proved its popularity among audiences. The classical LIEBELEI, as a supreme production accordingly, is truly a milestone that stands on its own. Following Christine's thoughts in the movie, viewers are deeply influenced by its romantic mood and its concept of 'eternity.' What is 'endless?' Longer than one lives...perhaps...but not longer than one loves.

dbdumonteil

This is the second version of a well known tale;the first was made in the silent era;the third,"Christine" ,a Pierre-Gaspard Huit effort ,was made to capitalize on Romy Schneider's huge success in the late fifties:she took on her mother Magda's most famous part.Max Ophuls 'work is much superior:more than the 1958 Christine ,it shows the difference between the two lovers's milieus:the dashing officer in his aristocratic world and the young girl's working class ;the scene at the opera theater with its cheap seats is revealing.For the boy,the girl is only a liebelei :hadn't Franz been killed,it's not sure that His love would have lasted.Christine's love is sincere ,she loves the officer with all her heart ,but her lover's world is not the same as hers ,his friend's relationship with Mizzi makes love a figure of fun (the scene when the husband unexpectedly enters the apartment) The final scenes climax the movie:the song which Christine performs on stage looks like a dirge and sounds like an omen ;the duel-which predates another Ophuls movie "Madame De..." and the heroine's suicide .Most of Ophuls works deal with woman's plight :his heroines are born to suffer : "la signora di tutti" "letters from an unknown woman" " Sans Lendemain" "Madame De " "Yoshiwara"...even when he chose real characters (Sophie Chotek in "De Mayerling A Sarajevo" or "Lola Montes") ,he made them the victims of a male society.In his canon,only the Courtezanes (Mizzi) or the whores ("Le Plaisir") who accept the rules of the game of the macho society can get away.

zolaaar

The camera of Franz Planer follows the protagonists in long tracking shots, observes precisely the development of an affection and later deep love between Fritz (Wolfgang Liebeneiner) and Christine (Magda Schneider) during the nightly walk through the sleeping city and their endless swings of waltzing through the empty coffee bar. It is also great how Ophüls exemplarily trusts in the viewer's imagination to make things visible. The couple has forgotten the world around them, being only close together, overwhelmed by the feelings, which suddenly arise in them. The slow waltz resembles a soft hug, but the melancholy in this dance is perceptible and especially Fritz, who has a secret tête-à-tête with a bored baroness, seems to fear, that the love for Christine might not have a happy ending.And last but not least some words about Gustaf Gründgens who plays the cheated baron: In the scenes, he is acting mainly only with looks, with stringent, frigid looks, that whoosh across the room like bullets. The precision of his performance is masterful and probably the best in this film.

Michael Pichlmair

Concerning Spaces, Ophuls' film is mainly focused upon camera movement. Some of the longer shots are especially remarkable. For example, in the scene when the Baron comes home for the first time and the lieutenant has great luck that he had left and hides behind a column from the Baron, who suspiciously and hesitatingly walks up the stairways, a circular shot is used. This same circular shot is repeated again in a later scene when the Baron runs up the stairway when he wants to condemn his wife. Shots like this always have significance in Ophuls' films. The reason for the Baron's special movement on his way upstairs, and the fact that his wife was deceiving him, was the same in both scenes, although he did not yet know the truth in the first scene. In the second scene, he knows for certain and is therefore running with all of his might, fueled with hate and anger.Ophuls films contain a myriad of details that one would not recognize when seeing the film just once. In the first scene, the opera scene, one might find the film-technique of 'enunciation.' Before the performance starts, one can see an eye-pair hiding behind a mask in the wall, followed by long shots over the auditorium. This makes the spectator feel that this masked figure, which is actually the opera director, is the camera and the enunciator, and therefore is identified with him. A remarkable long shot is also present in the gorgeous love scene of Christl and Fritz, as they glide in a sleigh through the snow-covered wood in the winter-landscape. As they talk about eternity, variation is created with some full shots of the couple. The same feeling is transmitted in the last scene, after Christl's death, where one can only see the marvelous picture of the snow-covered trees and only hear the off text saying: 'I swear that I love you. for all eternity', on that place where happiness once seemed to be assured. It makes the spectator re-live the first scene and be aware of the dramatic fact, that all of these beautiful feelings are gone, and in addition, Christl passed away believing that Fritz had cheated her the entire time. On the surface, Liebelei seems to be a really nice love story about two people meeting and fancying each other, but due to circumstances outside of their relationship, the love story ends in tragedy. But the main idea of the film is about something deeper. Arthur Schnitzler, who wrote 'Liebelei,' enjoyed great success with this theatre-play. Schnitzler's work was sometimes seen as another 'bourgeois sorry affair' (ger. Bürgerliches Trauerspiel), which always has the main theme of a love affair between people of different social classes. Although Vienna had very rigid rules in 1900 and Fritz is obviously from a higher class than Christl, this was not the main focus of the story. The actual theme is timeless and universal: misplaced male honor. The duel in the end was just the tip of the iceberg. It was a common occurrence, especially among officers, to fight a duel whenever this 'honor' was damaged, even though it has always been illegal, of course. Theo, the victim's best friend tries to change the course of destiny as he goes to his superior, the colonel. This is the scene where you see the conflict between two worlds colliding. On the one hand you have the militarily strict world, but on the other hand, there exists a humane world. In the humane perspective, humans can err, can love, and also forgive. The Baron's position is clear. Everyone expects him to act in a certain way in this situation. Despite this, the Baron is the evilest in having misplaced honor. Theo is the one caught in the middle, the only one who understands this madness, and this position is the reason for his desperation.Gestures are often seen in Ophuls' film as well, where he tries to replace words by body movement, gestures, faces, camera movement, lightning, etc. For example, there was never a cigarette smoked as by Gustav Gründgens (the Baron), concentrating all his hate and anger in his smoking.One of the obviously greatest sequences is the final one, where Theo (Eichberger), Mizzi (Ullrich) and Christl's father (Hörbiger) sit opposite of Christl (Schneider) at the entrance of her chamber and try to tell her about her lover's (Liebeneiner) death. The Camera is mainly on Christl showing in a long extreme close up her realization about what has happened. She doubts that Fritz ever loved her since he lost his life on a duel over another woman. Her face shows pure desolation and desperation as she stammers out her thoughts. One must have a heart of stone to not shed some tears or at least have a lump in the throat when seeing this scene, which wouldn't have had half of this effect if it were filmed from a medium long shot perspective.See synopsis above as well