Teyss

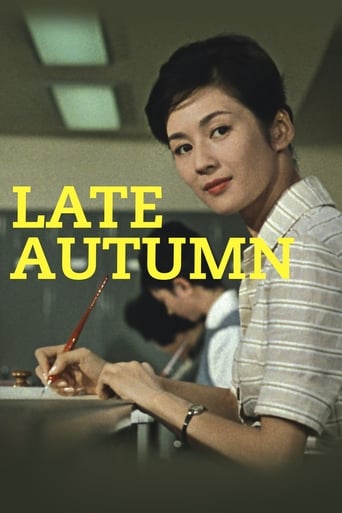

The qualities of Yasujiro Ozu's movies are complex to demonstrate: simple stories of simple people, everyday dialogues, slow pace, fixed cameras, images with plain beauty. Also, they probably have more meaning for a Japanese audience who better understands their cultural, visual and historical references.On the surface, many of Ozu's films seem similar: the plots look familiar and the style is recognisable among many. Yet he always introduces variations and progresses in his form with perfectionist care. He is a craftsman of cinema and as such, even subtle differences create an altogether new piece of art, like a painter representing different versions of resembling subjects.Ozu was somewhat resistant to change. When he directed silent movies and the industry moved to talkies, he was unwilling to follow: he did so when he had no choice in 1936, nine years after the introduction of sound. He continued directing black and white movies until 1957 as he did not want to switch to colour. When he finally reluctantly did so, he liked it so much he only directed colour movies… However because he died in 1963, there are only six of these, in a carrier of more than 50 films. It is unfortunate, because his use of colour is masterly, as notably shows in "Late Autumn".His masterpiece is considered to be "Tokyo Story" (1953). Nevertheless, despite all its qualities, I still prefer "Late Autumn" (original title "Quiet Autumn Day"). Its story is close to "Late Spring" (1949), but notably differs by the style (of which colour is only an element) and the humour.*** WARNING: CONTAINS SPOILERS ***It is the story of two middle-aged men, Mamiya and Taguchi, who want to find a husband for the young Ayako, daughter of their late friend. However Ayako lives with her mother Akiko and does not want to leave her alone, so the ploy is to marry Akiko to their widowed friend Hirayama. As we see, the movie is about arranged marriages: the two women are tools of the male manoeuvre. But this will partly backfire, tactically and emotionally.The movie shows a traditional society turning into a new one. On the one hand: arranged marriages, etiquette, dominant males working in top positions while their wives stay home. When Taguchi comes back home, he drops his clothes on the floor for his wife to pick up. His daughter prepares a bath for him. They think everything will happen according to their plans. Hirayama, however, is on the side: less dominant, more passive.They believe they can be allowed anything. Mamiya arrives late at the memorial service at the beginning and makes a disrespectful remark about being too early. They make ill-placed allusions about a waitress being ugly, in front of her. When Hirayama is turned down at the end, the two other men don't care. Their intentions are decent, but because their mental frame is old-fashioned, they act clumsily. On the other hand, their entourage escapes their control: this is when is movie is most humorous. Their wives make sarcastic comments, either in front of them, either behind their back (i.e. the conversation between the two ladies). Their children resist their authority, talk frankly, answer back. Taguchi's young son makes insulting gestures behind his father's back. His daughter married because of love, not rationale, which her father does not understand. At one point, Yuriko, who has a junior position in the company, scolds the three bewildered men. Already funny for a Western audience, this scene must have been a shock for 1960s Japanese spectators. Afterwards, she fools them by bringing them to a restaurant that is actually her parents'. And she manipulates Hirayama by promising Akiko will marry him.More profoundly, the general stratagem reveals concealed passions: Mamiya and Taguchi were in love with Akiko, and actually still are. They are jealous Hirayama can marry her. They appear weaker than are willing to admit, manipulating others yet unable to acknowledge their emotions, while their wives perceive their hidden feelings. Bygone loves, deceased spouses, fading traditions: it is a nostalgic movie.To illustrate the story, Ozu magnificently uses colours. Objects are flashy blue, green and most noticeably red. On the contrary, characters mainly dress in conventional tones. They are sometimes seen behind colourful objects in the foreground (bottles, bowls, glasses, cups, etc.). Also, Ozu occasionally introduces "empty" shots without persons. We feel as if objects had more presence than characters: the latter seem to play stereotyped roles. They have plain conversations, gossip, focus on simple ideas, spend their time drinking; they frequently look dull, indecisive, awkward or immature. The point of view on characters is slightly satirical. Exceptions are the quiet yet strong Akiko and the outspoken Yuriko.To be honest, until the end, the movie is "only" very good. However the last ten minutes are for me among the greatest in cinema history. Akiko and Ayako make a last trip together, which is very nostalgic and moving. Then, the marriage is dazzling, supported by ravishing music. Everybody is motionless and silent, like objects precisely. A few gazes loaded with emotions summarise the whole story: Akiko looks melancholic, Yuriko happy, Hirayama resentful, Taguchi's wife embarrassed (for Hirayama). Apart from Yuriko, there is no sign of joy. The newly wed, very handsome in their costumes, are stiff like statues, their faces without feelings. It feels as another "empty" shot. The entire scheme has culminated to this hollow formality: the final irony, wrapped in delightful form.After a bitter scene where Hirayama expresses his rancour, the movie closes on Akiko. She has a sad and gentle look: she is alone, but her daughter can be happy, so she thinks. Her sacrifice is touching. The final image shows her corridor where three lights are usually on; now there are now only two since the third one is dark: Ayako is gone, Akiko is left with the remembrance of her late husband.

samhill5215

Of Ozu's trilogy on marriage Japanese style this one is my favorite. In fact many of my comments apply to the other two, Late Spring (1949) and Early Summer (1951). All three deal with the concept of marriage as seen in traditional Japanese society and even though to my western eyes it seems antiquated, Ozu manages to present it as a sensible, inherently logical way to pair two people. But what ultimately attracts me to his work is his presentation. The plot unfolds in a slow, languorous way. It's linear but with gaps in time which are fully explained so that we are not left guessing as to intervening events. What we see and hear is the important stuff. We, in essence, are eavesdropping on intimate family conversations, the kind of things discussed at every dinner table, things important to a family but more or less irrelevant to the outside world. Somehow Ozu makes that interesting. Naturally the actors play an important part and the presence of two of my favorite Japanese actors, Setsuko Hara and Chisu Ryu, in all three are a definite plus. So why is this one my favorite? Humor and lots of it. The first two are rather serious, drama-filled works where the characters exhibit much angst. Late Autumn on the other hand is light and airy, there's a bounce to it, and it's filled with a lot of sexual innuendo that is completely absent from the others. It's as if Ozu was saying to us that the post-WWII years was a time for Japan to buckle down to the serious work of rebuilding society. By 1960 the joy of living had returned to his country. It could afford the bumbling of three well-meaning and occasionally lecherous men whose efforts at match-making were only half successful.

Ed Uyeshima

Even though the comparison is obviously intentional, Yasujiro Ozu's 1960 film is really a variation on his classic 1949 father-daughter drama, "Late Spring". He goes further with this parallel by having the wondrous Setsuko Hara, who played the daughter in the original film, play the mother in this one, even though only eleven years have elapsed. Gone is the alternately feisty, flirtatious and petulant manner that marked her earlier performance as Noriko, and in its place is that remarkable stillness and quiet warmth in her portrayal of Akiko that marked the best of Hara's later performances. She was barely forty during filming, yet she carries the gravitas of her role with uncommon ease. What remains consistent between her two performances is the unearthly devotion which ties the characters intractably to the world in which they have grown accustomed.Ozu wrote the quietly perceptive script with longtime collaborator Kogo Noda, and the filmmaker's trademark touches - the narrative ellipses, the lack of melodrama, the low camera angles - are all here in their emotionally resonant glory. This time, the character of Akiko has such an easy sisterly bond with her daughter Ayako that neither has an interest in dating or marriage. While Akiko's situation is more or less accepted by society, Ayako's single status is a point of consternation, especially for three friends of Akiko's late husband, all of whom express feelings of unrequited love for the unavailable Akiko. They are jointly intent on finding Ayako a suitable husband and find one in Goto, a young, well-mannered bachelor with a suitable career. Akiko, however, demurs at the possibility of matrimony which leads the story through its inevitable paces.Yôko Tsukasa is pretty and affecting as Ayako, though honestly no match for the younger Hara in the earlier film. More of that uninhibited spirit is present in Mariko Okada, who plays Ayako's friend and colleague Yuriko. She has a terrifically abrasive and amusing confrontation with the trio of embarrassed matchmakers, and the result comes across as a bit of an imbalance to the viewer now since Yuriko's Westernized independence is more compelling than Ayako's more innate diffidence. Adding more to the comedic aspects of the story, Shin Saburi, Nabuo Nakamura and Ryuji Kita play the matchmaking trio almost like a Shakespearean comedy troupe. Interestingly, Ozu uses a decidedly Italianate-sounding score to underscore the action, a nice unpredictable touch. This well-preserved film is not as essential as "Late Spring", but it is a worthy addition to Ozu's filmography.