Smartorhypo

Highly Overrated But Still Good

Rio Hayward

All of these films share one commonality, that being a kind of emotional center that humanizes a cast of monsters.

Jenna Walter

The film may be flawed, but its message is not.

Bob

This is one of the best movies I’ve seen in a very long time. You have to go and see this on the big screen.

Alonso Gil Salinas

It is a really good film. Though I would highly recommend reading the book in which it is based ("Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil") to fully appreciate the dialogue, the film conveys what Hannah Arendt really wanted to communicate: that an external situation highly influences (not to the point of determining, because there are always exceptions) the behavior of "normal" people. In this case, totalitarianism and evil behavior. I would only add that some commentary should have been included in the final credits about what happened regarding the polemic she caused with the passage of time. I think a paragraph I read in an Internet essay by Dr. Daniel Maier-Katkin (http://www.hannaharendt.net/index.php/han/article/view/64/84) is very clear about it: "The tide of history since then has been mostly with her. In politics this is due to the widespread opposition especially among students and intellectuals to the Viet Nam war in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The conduct of American leaders – Lyndon Johnson and Robert McNamara, and then Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger – brought home the idea of "banal" evil. In social science, landmark studies of obedience to authority by Stanley Milgram at Yale and of prisoners and guards by Philip Zimbardo at Stanford gave shocking evidence of the extent to which ordinary people could be induced to harm others. Among historians, with the notable exception of Daniel Goldhagen's book Ordinary Germans: Hitler's Willing Executioners (which attributes the Holocaust to a tradition of exterminationist anti-Semitism in German culture) recent scholarship on the Third Reich – Ian Kershaw on Hitler, Robert Gellately on the S.S., Christopher Browning on the Einsatzgruppen – tends to confirm Arendt's thesis that ordinary people were complicitous with the Nazi regime for reasons best characterized as banal. In international affairs, the collapse of Soviet totalitarianism and recent genocidal catastrophes in Bosnia, Rwanda and Darfur have reinforced the idea that great evil may arise from the false beliefs and banal motives of ordinary people". The above mentioned Dr. Zimbardo published in 2007 a book titled "The Lucifer Effect" in which he explains how good people turn evil. Years before, he had testified for the defense of a guard at Abu Ghraib prison rejecting the idea that the events did not reflect the particular military situation in which they happened. Of course, this is difficult to accept, because it implies much more culpability on the higher authorities which allowed such a "situation" to emerge in the first place. I guess the argument suggests that it is far more difficult to accept that there is a high probability that "normal people" like ourselves can fall into evil behavior due to a horrendous and shocking situation in which, for whatever reason (and without fully realizing it) we might fall; than conceiving an evil nature (an awful exception) in he who behaves in such a way. Anyway, do not misunderstand the idea. The fact that the situation can have a predominant role does not exculpate the perpetrator. (spoiler alert) As Hannah Arendt's last phrase of her book (talking to Eichmann's about his overall behavior) states: "This is the reason, and the only reason, you must hang".

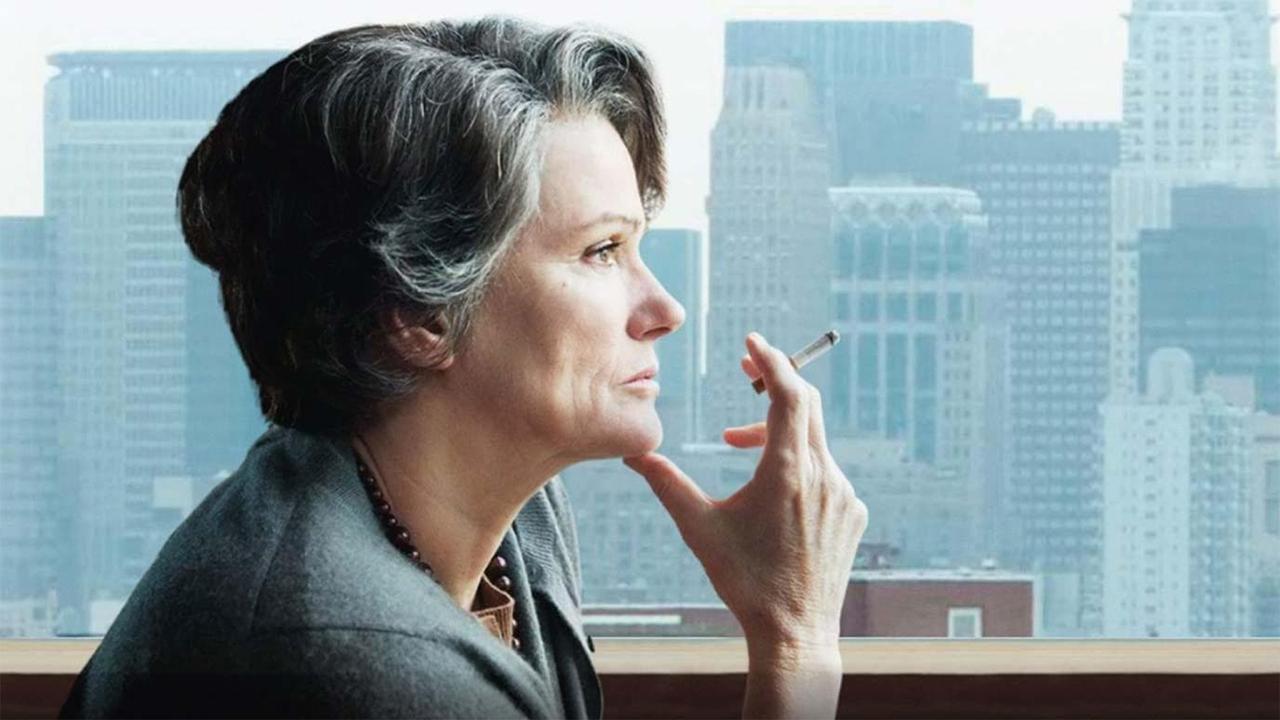

blanche-2

This is a fascinating look at Hanna Arendt, a German-American philosopher who in 1961 reported on the trial of Adolf Eichmann for the New Yorker. A huge controversy erupted.Arendt left Germany in 1933 for France, but when Germany invaded France, she found herself in a detention camp. When the film begins, she is a happily married woman with friends such as the writer Mary McCarthy, and she is a professor at, among other places, the New School in New York City.Hanna is very excited about covering the trial, but her husband, Heinrich, is afraid it will take her back to those dark days. While observing Eichmann, Arendt is struck by the fact that he was an ordinary man with nothing special about him. This causes her to think about the nature of evil itself. She decides that he's not a monster but a person who suppressed his conscience in order to be obedient to the Nazis. She thus created the concept of the "banality of evil."She believed also that some Jewish leaders at the time had fallen into this trap and unwittingly participated in the Holocaust. Her critics failed to understand her meaning.In some camps, her New Yorker articles were not well received, as she was seen as a heartless turncoat who blamed the victims. Hanna has to defend her ideas, and the price she pays for them is high.Barbara Sukowa does a magnificent job as Arendt, showing the woman's brilliance, courage, affection for friends and family, and hurt when some people she loved turned against her. It's surprising that she was met with as much disdain as she was -- but Arendt did not believe in blind adoration of any group. She took people on an individual basis. As far as the banality of evil, evil has always had the ordinary face of people sitting back and doing what they're told. Or, as Martin Luther King said, doing nothing. I'm sure many of us have experienced this in the workplace -- I know I did. It's then that you realize the true nature of most people. Everyone can say they have ethics - but do they have ethnics when they stand to lose something?Beautifully directed by Margarethe von Trotta, who also co-wrote the screenplay. A difficult subject made clear, a complicated woman understandable -- no small feat. A thought-provoking film.

l_rawjalaurence

Other reviewers have questioned the historical accuracy of Margarethe von Trotta's portrayal of Hannah Arendt (Barbara Sukowa) and her opinion of the Jewish leaders as expressed in her NEW YORKER articles on the trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961.As a piece of film-making, however, HANNAH ARENDT grabs the attention and does not let go throughout its 113-minute running- time. As portrayed by Sukowa, Arendt comes across as a forthright person, not frightened of expressing her opinions and responding to any intellectual challenges from close friends such as Kurt Blumenfeld (Michael Degen). Yet beneath that tough surface lurks a profoundly disillusioned person, as she discovers to her cost that her great teacher and mentor Martin Heidegger (Klaus Pohl) does not practice what he preaches. Although insistent on reinforcing the distinction between "reason" and "passion," Heidegger takes the "passionate" decision to associate himself with the Nazi party, and thereby embraces their totalitarian values. Like Eichmnann himself, he chooses not to "think" but to commit himself to an ideology that actively discourages individual thought. The sense of shock and disillusion Arendt experiences inevitably colors her view of the Eichmann trial. Director von Trotta includes several close-ups of her sitting in the press-room listening to the testimony of Eichmann, his accusers and the witnesses, a quizzical expression on her face, as if she cannot quite make sense of what she hears. She cannot condemn Eichmann, because he has simply followed Heidegger's course of action.Once the articles have been published, Arendt experiences an almost unprecedented campaign of vilification. Although she is given a climactic scene where she defends herself in front of her students (and her accusers within the university faculty), we get the sense that she is only doing so on the basis of abstractions; her personal feelings are somehow disengaged. She is far more affected when her one-time close friend Hans Jonas (Ulrich Noethen) vows never to talk to her again on account of her views. Philosophers might be able to make sense of the world, but they often neglect human relations.Consequently our view of Arendt, as portrayed in this film, is profoundly ambivalent. While empathizing with her views about the banality of evil, which reduces people to automata as they claim they were only carrying out orders, even while being involved in atrocities, Arendt herself comes across as rather myopic, so preoccupied with her ideas that she has little or no clue about how they might affect those closest to her. It's a wonder, therefore, that Mary McCarthy (Janet McTeer) chooses to stick with her through the worst of circumstances.Ingeniously combining archive footage of the Eichmann trial with color re-enactments of what happened during that period, HANNAH ARENDT is a thought-provoking piece, even if we find it difficult to identify with the central character.

integrityandvalues

This film helped me to forget that it was a film. Subtle, intelligent but mostly telling a story imperative to the 21st century. By making links throughout Arendt's personal life and development as not only one of 20th century's most brilliant thinkers and philosophers but a sentient passionate and moral woman, juxtaposed with her work—and the aftermath of—her New Yorker articles on the war crimes trial of Adolf Eichmann, Arendt, without making such a projection, articulates what this current era of humanity suffers from most: "The banality of evil". The film brings this point into sharp focus without as much saying this is what we need, but the timeliness of it is most certainly intentional.This film also beautifully, and again subtly, captures the state-of-mind of an era: One of calcified righteousness among others who cherished clarity of mind, goodness and intelligence, and a style of humor and affection from which those things flowed freely.See the film to understand exactly what all this means and why Arendt's topic of the "banality of evil" is so important for today's crises facing humanity.