tjitfilm

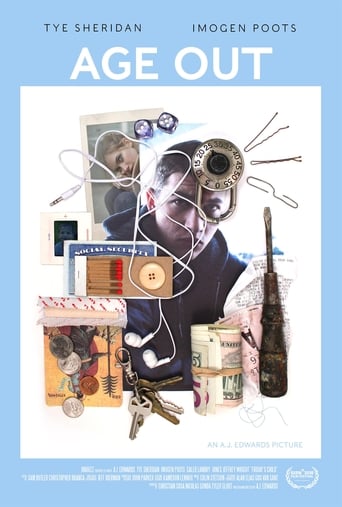

Edward's Friday's Child is Polanski's Oliver Twist meets Andrea Arnold's 2016 road drama American Honey.Edwards, editor for Terrence Malick on his 2012 drama To the Wonder, brings the brutal decision 25,000 orphans face annually in the US to the cinema in this hauntingly real drama: whether to pursue a higher education and take on immense debt, or forego education early to fight for their place in the world.At its core, the film has a harsh honesty that will leave the audience helpless in its wake. Edwards doesn't shy away from confronting the audience and employs a full range of cinematic techniques to create as visceral and personal experience. The end result is drama that will leave the viewer shaken, gasping, and somewhere deep down, confused by the guilt and anguish they feel by the pounding resolution of Edward's cinematic masterpiece.Right off the bat, you'll notice Edwards chooses to shoot his entire film on the same wide lens (when I mean wide, I mean very wide: probably around in the 12-18mm range). It distorts space, makes it bulbous and deep, and draws attention to the environment very consciously. Inspired by American and German photographers from the 70s and 80s, Edwards explains that when we look at the world, we're not switching constantly between different lenses, rather in reality, our eyes see through one set of lenses. It is a very confrontational choice, that forces the viewer into the rest of the world in Friday's Child. You don't get to live the drama of the film without the harsh reality it is placed in.Tye Sheridan, Imogen Poots, and Caleb Landry Jones have standout performances. They feel real and present; the only ounce of melodrama that leaks in is at the very end of the film. Aside from that, they move about the film with the listless pace you'd expect from people trying to piece their lives together. It isn't acted - scenes are startlingly authentic, starting from minute details like the awkward gait Tye Sheridan at Richie's first high class evening party, or the reckless stride of Caleb Landry Jones's character Swim as he struts around a hotel he has no business living in. Edwards often brings the camera right up to the actor, close enough to hear their shallow breathing and notice the clenching of their jaws. The intensity of the performance lives through its subtlety, a testament to Sheridan, Poots, and Jones.The tone of the film, largely controlled by the rich kodachrome color palette and the pressuring soundtrack from rock artist Colin Stetson (he worked on Arrival and more recently, Hereditary), is heavy and oppressive. The 3:4 aspect ratio, in combination with the unrelenting drone of the soundtrack, can leave the audience feeling just as trapped as Richie himself. It isn't without catharsis, however: in the middle of the film, Richie elopes with his new girlfriend to the midwest, and the sound track recedes to reveal the gentle ambience of the country, the colors calm down to a comfortable temperament, and the sky opens as the frame expands in wondrous 2.4:1 aspect ratio. You can almost hear the theater breathe a collective sigh of relief.Ultimately, the film revolves around freedom. In the opening minutes of the film, Richie's school counselors tell him, "You know what we call aging out? Emancipation." Edwards presents us with an authentic story rooted in the real problems of orphans all over the United States, while pressing us to live out their struggles with realizing what freedom really means in the "Land of the Free". While we can never completely understand the stories of these orphans from this side of the camera, Edwards offers us something remarkably close that, if not moving us into action, forces us to truly celebrate and fight for Emancipation some of us have the luxury of possessing.