Lovesusti

The Worst Film Ever

Tyreece Hulme

One of the best movies of the year! Incredible from the beginning to the end.

Roman Sampson

One of the most extraordinary films you will see this year. Take that as you want.

Delight

Yes, absolutely, there is fun to be had, as well as many, many things to go boom, all amid an atmospheric urban jungle.

Vonia

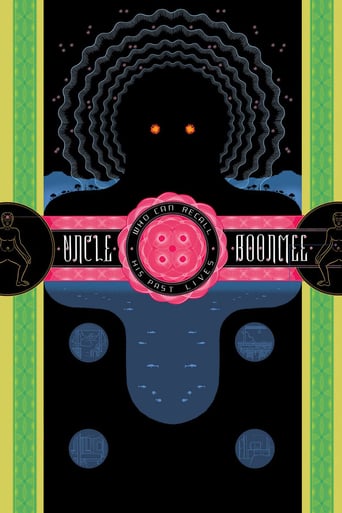

Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (Thai:Loong Boonmee raleuk chat) (2010) Afterlife visits A dying man in Thailand In his final days. His late wife, a missing son. Ever so casual, The two materialize At dinner's table. Mystifying glowing red eyes, Floating see-through shapes Inexplicably troubling. Reincarnation, He has lived many past lives. Once he was an ox, A catfish in a cave has Sex with a princess. Philosophical musings, Cultural concepts, Spiritual reflections, Communist concerns, Metaphysical ideas, Cosmological. Buddhism, Dualism, Eroticism, Illusions and memories, Confused? So was I. Excruciatingly slow, The beautiful shots, Intellectual ponderings, Few and far between. I like knowing characters. Abstract and distant, I could not connect nor care. I tried, really tried, Uncle who I won't recall. A dream? More like a nightmare. (Choka (長歌 long poem)) was a storytelling form of poetry from the 1st to the 13th century, known as the Waka period. The choka is an unrhymed poem with the 5-7-5-7-5-7-5-7...7 syllable format (any odd number line length with alternating five and seven syllable lines that ends with an extra seven syllable line).

Ilpo Hirvonen

"You don't have to understand everything," explains Apitchatpong Weerasethakul about his Palm d'Or winning, enigmatic and ambiguous "Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives" (2010) in a 2010 interview with The Guardian. This remark by the author of the film is very simple but even more relevant as such since it is, I believe, precisely the unconscious demand for clarity and unity, a rational need to understand which leads many spectators astray when it comes to Weerasethakul's cinema. The torment of understanding is what ruins the viewing experience for far too many, making it harder for them to see the simple beauty of films like "Uncle Boonmee".In all its simplicity, "Uncle Boonmee" is a story about a dying man. His family and other close ones take care of him as he requires daily doses of dialysis. On one night, his dead wife appears as a ghost to chat with him and his caretakers at a serene veranda only to be followed by the unexpected arrival of his long lost son who has now turned into an ape with glaring red eyes. A surprisingly calm discussion between those involved takes place, including a few flashback sequences, which slowly lead the way to a new day, a journey to a cave, and finally a detachment from this story to another. There are no spoilers here because they do not exist in the Weerasethakul canon. His films are less about stories and more about images. The gulf between those who love Weerasethakul and those who despise him begins in this division: one tries to find a coherent and consistent story in the images, explaining objects in the screen space as symbols for something much clearer and less vague, while the other tries to embrace the images themselves not as symbols but as what they are, images. One could think of it as cinematic music, a peculiar language of the rhythm which does not call for conceptual understanding but a pre-reflective reception. In addition to Weerasethakul's style, consisting of long takes, slow editing rhythm, large shot scales, lack of non-diegetic music, and a relentless use of ellipsis, which might create discontent in some spectators, there is also a more thematic, or "content-oriented," explanation for this discontent. "Uncle Boonmee" is about crossing boundaries. Halfway into the film, one is ready to accept a dialogue between people and ghosts as natural or a sexual encounter between a princess and a fish as nothing out of the ordinary. Conceptual distinctions into categories such as past and present, man and woman, animal and human, nature and culture, reason and emotion, dream and reality coalesce and disappear. This is why they will not serve a spectator trying to find a conceptually understandable story in the pervasiveness of the images. One could see the circularity of the narrative as a reflection of reincarnation, but even this seems too categorical. To me, there is only a fragmented narrative without clear boundaries unfolding like a beautiful poem without the burden of words. Hopefully this has not come off as an attack. The foregoing discussion has been nothing but a modest attempt to open streams of curiosity. I have tried to explain the division between those who admire and those who despise "Uncle Boonmee". I have located the latter's discontent in Weerasethakul's unique style (using slowness and serenity to create cinematic lyricism which challenges our conceptual understanding) and the film's thematic treatise on crossed boundaries (combining purported conceptual distinctions into one to create a non-linear narrative which challenges our conceptual understanding). Clearly this is not everything, but it is "everything" in less than one thousand words. To Weerasethakul, the discontent of some means nothing but the success of his cinema: "if I make a film that divides the audience, I feel like that's a certain level of success," Weerasethakul tells The Guardian. In the spirit of this remark, there is nothing left to say other than a request to give Weerasethakul's cinema a chance rather than condemning it on the basis of one's own purported categorical distinctions. Like in the films of Ozu or Bresson, the objects in the screen space are not symbolic; the images themselves are what count -- and it is those images where Weerasethakul's cinema returns to.

aaronadoty

This film was difficult to watch. I realized part-way through that I am accustomed to being told by the soundtrack what to think and feel about a scene in a movie. For the most part, Uncle Boonmee gives you no such clues. Without them, I had to make up my own mind about how to respond to each scene. As a viewer, you are given natural background noise and an ensemble of fairytale characters - the monkey spirit, the catfish spirit, the princess, the club-footed woman, the monk and the ghost - and you are left to figure out the rest by yourself. There is plenty of scope to do so: the ordinary daytime scenes and the surreal nighttime events both proceed at a languid pace, and the characters respond to even the most disturbing developments with polite calm and gentle acceptance. It is fortunate that the mood is so relaxed and the progress of the film so sedate, as there is a lot of weirdness to process. Think Gozu, with all the violence, theatrics and narrative removed.

garcalej

I'll be frank. Whether or not you enjoy this movie will depend largely on whether or not you are a die hard film buff or a casual movie goer looking for a story. If you are the later, then aside from the eerie sight of the red eyed Monkey Spirits, you will come away disappointed.That said, there is much in Uncle Boonmee to like, but like the Buddhist aesthetic the film is steeped in, you have to be ready for it. Because this is one film that demands a lot of patience of the viewer.Set in rural Isan Province, Thailand, the story follows the last days of a well to-do farmer, the titular Boonmee, who is dying of a terminal illness. Like all dying men, Boonmee can't help but wax philosophic, both on the nature of death itself and on his own past mistakes, and one night while eating with his family is suddenly and abruptly joined by two spirits, the first of his dead wife, Huay, the second that of his missing son, Boonsong, who has inexplicably been transformed into a black monkey. Anyone even remotely familiar with the prior work of Director Weerasethakul (try saying that with a mouthful of marbles), particularly Tropical Malady, will know that such surrealism is a common theme in his films, with its signature mix of traditional Thai Buddhism and animist lore. As in Tropical Malady, the day belongs to the living and the mundane, but night brings on ghosts, animal spirits, the shades of ancestors, and the inner musings and anxieties of Weerasethakul's characters.The film itself feels much like a Buddhist temple; with its long uninterrupted and unadorned shots, and its devotion to capturing trivial moments, it is not so much a vehicle for storytelling as contemplation. The last film to be shot with celluloid as opposed to digital, it is the director's self-admitted funerary ode to a dying medium.