Perry Kate

Very very predictable, including the post credit scene !!!

Twilightfa

Watch something else. There are very few redeeming qualities to this film.

Micah Lloyd

Excellent characters with emotional depth. My wife, daughter and granddaughter all enjoyed it...and me, too! Very good movie! You won't be disappointed.

Portia Hilton

Blistering performances.

classicsoncall

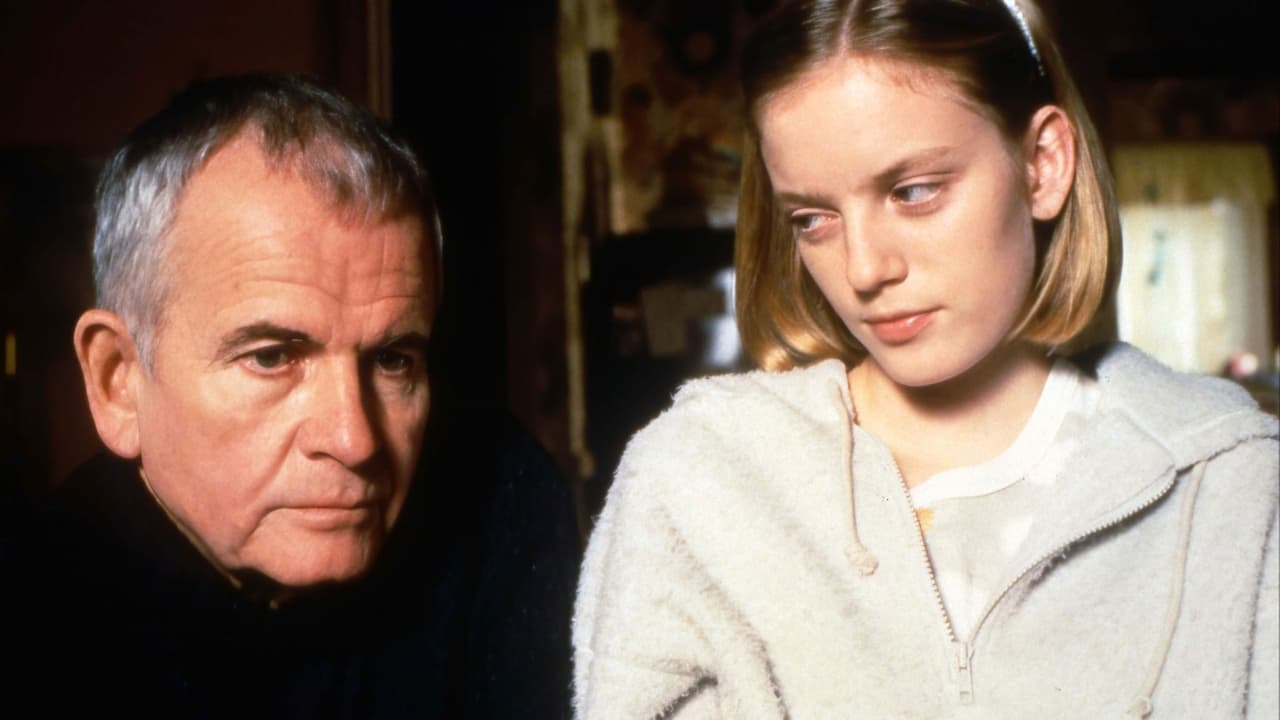

I have to admit, I was left baffled by the conclusion to this story with the young girl Nicole (Sarah Polley) lying about the speed of the bus when it lost control and sank into the river. I generally understood the motivations of all the other characters, and unlike a lot of reviewers for the film, it didn't strike me that attorney Mitchell Stevens (Ian Holm) was your typical ambulance chaser out to make a quick buck. I thought all the while he was attempting to arrive at some measure of justice and closure for the small town's residents. In that regard, it wasn't unusual that Billy Ansel (Bruce Greenwood) would challenge Stevens; as the bus mechanic he might have been implicated for negligent service. On the flip side, his own kids who died were on that bus, so that argument could have been summarily dismissed. The linchpin for this film in my opinion was the relationship between Nicole and her father Sam (Tom McCamus). Their scene together in the barn creeped me out to such a degree that it affected an appreciation for the rest of the story. Quite honestly, had a resulting trial revealed Sam's abhorrent sexual abuse of his daughter, he would have had a lot to account for. The constant exchange of guilty expressions between Nicole and Sam while she was giving her deposition really bothered me. By lying, Nicole took him off the hook, and maybe that's what she wanted to do. But I didn't see her as mature enough to make that decision in order to bring the town it's need for healing. As one of the crash survivors, she was entitled to her peace of mind, but coming out of the picture, she would well continue suffering both mentally and physically because of her father's abusive behavior.The film is told in non-linear fashion and starting out, it can be a little confusing. There's a parallel story of attorney Stephens' inability to deal with a daughter who's drug history and promiscuous behavior has resulted in her testing HIV positive. The background narrative of the Pied Piper poem seems to imply the method Stephens employs to get the town's residents to follow his lead into a major lawsuit. The child left behind in that story would refer to his daughter Zoe (Caerthan Banks). As a cinematic device, I don't know that it really had any impact on the narrative other than to pad out the movie. For this viewer, the entire experience felt like something of a downer with no inspiring message to ease the pain of the underlying tragedy.

two-rivers

"The Sweet Hereafter" is another denomination for paradise, as it is to be enjoyed in afterlife. In the Robert Browning poem about the Pied Piper, which is read by Nicole, the only child surviving the bus accident, one of the kids is lame and cannot follow the call of the Piper. It is therefore "bereft of all the pleasant sights they see" and henceforth has to endure the dullness of life in a town that has been deprived of all playmates.The same happens to Nicole, who will be confined to a life in a wheelchair while the entire young population of the little town of Sam Dent, British Columbia, is now enjoying the pleasures of heaven. Her sadness is understandable, but it is equally plausible that it should lead to anger and the urge to revenge.It is obviously the lawyer Mitchell Stephens that provokes her indignation. He can also be seen as a kind of pied piper, but not one whose commitment leads to the entrance of paradise. His goal is the fulfillment of earthly materialistic pleasures, and therefore he tries to persuade the relatives of the deceased children to file a lawsuit against the bus company for damage. In case of success, he would also benefit from the verdict and encash one third of the allocated sum.The necessity of mourning for the bereaved ones has been substituted by sheer business matters, and the greed for money has become the new incentive. And it is Stephens who has to be blamed for that change of disposition.But there is no compensation possible for the loss of human life. Nicole understands that and makes a fateful decision. Being chosen as a chief witness and asked in a pretrial-hearing about the circumstances of the bus accident, Nicole consciously gives a false testimony accusing the bus driver of having driven at excessive speed. Now the planned trial against the bus company cannot take place, and Mitchell Stephen's materialistic dreams are shattered.Standing in clear opposition to the girl, whose desire it is to get access to heaven, that lawyer can truly be considered an advocate of hell. We get introduced to him when, right at the beginning, he is trapped in a car wash whose mechanism cannot be brought to a halt. It is here that he gets the first cellular phone call by his daughter Zoe who is equality trapped, as her drug addiction and her later-revealed AIDS infection has led her to a dead end of her life from which no deliverance route seems to be attainable.Certainly her father can do nothing to help her. When Zoe, whose name ironically means "Life", tries to contact him, we can see that her phone booth is located in a rundown area of a larger city - an image that can be seen as a metaphor for the desolation of her inner state of mind. She addresses herself to her father out of utter helplessness, and it is deplorable to see that he is unable to respond. The only thing he can do for her is to "accept the charges" for the call - another indication of a mind set only on materialistic issues but not prepared to offer the much needed spiritual help.Zoe nevertheless does make an attempt. She reminds her daddy of a childhood memory when they both were inside a car wash and she "started playing with the automatic window" - a story that, if we accept the car wash as an image for hell, reveals her strong desire of escape and thus approximates her character to the children willingly seduced by the Pied Piper.However, Mitchell Stephens is incapable of establishing a meaningful communication with his daughter - he thinks that she is merely "calling for money". It is only much later that he comes to a heart-breaking insight. When accidentally meeting a former childhood friend of Zoe on an airplane, he recalls another memory from the past, this time when his then three-year-old daughter nearly died from a spider bite. Although he does not clearly reveal it, the spectator senses that Zoe has now finally succumbed to her drug addiction - and therefore become just another victim of the Pied Piper's power of attraction.

chaos-rampant

Okay, so Egoyan has faded from view it seems, but for a while as he really was something. Exotica was powerful in exemplifying his paradigm. A narrator trapped in hurt that he constantly relives as performance, the entrapment as memory, the narrative of vaguely dreamlike connections as self. More than just some drama out there, it was a coda penetrating into something of the very process that gives rise to the ruminating mind; self. He extends it here.Once more a narrator who remains trapped in impotent hurt - a lawyer whose daughter has strayed in drugs - who is now approaching people much like him, heartbroken by childloss, to convince them of the need to find someone to punish and hold responsible. A larger view through this man. About us, unable to come to terms with the fact that life is transient and will sometimes break down for no reason. And how this freezes love, makes rigid our ability to remain supple in the face of mishap - and if this isn't the definition of love, I know of no other - and turns it into incessant ego.Egoyan is an intelligent mind in sketching his paradigm and again in how he pursues resolutions. Parents having been convinced by this bitter man (who is a storyteller working to construct a legal story that justifies) to throw their hurt outwards, turn it into recrimination, it's the surviving daughter who breaks the cycle of suffering for all involved. How she does it, again referencing narratives, is by fabricating a memory, fiction that requires a performance. It's not the truth of course, but it's what needs to be done so that fictions can be chucked away and simple acceptance can begin the work of mending. Yes, he can be obvious in spots and parallels, more so here than Exotica. He can be as simply lyrical as Kieslowski, as complexly layered as Medem. But seen overall, it's the larger awareness of life as flow that goes through many veils that makes this worthwhile. On these veils are seen the shapes of bygone life, mind itself as it wonders. He pursues this mind with an eye that is marvelously freed from the here and now to surge forward and back in search. This effort in film is far from novel, it goes back to Tarkovsky at least, but it's tuned to the same purpose; how to see with an eye that remains supple in the face of reality.And we can venture even further out to offer this view about the world that gives rise to this work. Egoyan can trace a past life for himself in a corner of that bygone world that centuries ago was overran by invaders from the steppe. He must be acutely aware of a past that is shrouded in ruin, the need to placate ghosts of memory. This is a world I happen to share with him, first Armenia, then Constantinople and all the way up to the Danube, that was wrecked in its physical reality, severed from it in so many ways, and a deep part of it has taken flight in dreams and memory, which is the subject of both this and his previous film.So is it any wonder that he draws fresh water from Tarkovsky's spring? It's a spring that both Parajanov, another Armenian, and Kusturica later would draw from, and it goes back in time in a deep way. Something to keep in mind while viewing him.

Artimidor Federkiel

A single horrific accident that reaps away dozens of children jolts a small town out of its reverie. The damage done is irreparable, and it's up to the lawyers to find a culprit, because after all someone has to be made responsible, big time... - Atom Egoyan's "The Sweet Hereafter", based on Russell Banks' novel bearing the same title, is a writer's/filmmaker's take on events that actually took place in Alton, Texas, in 1989 where the disaster involving dozens of fatalities led to an array of lawsuits to reach settlements as compensation for the deaths of the children. In the process people who shared the same trauma and grief became even further estranged from each other, despite or especially because of the reparations that were paid. Maybe the price tags put on the children were varying, but it was only a symptom - things could never be the same again. Whole futures perished with the lives lost in an instance, and the animosities the lawsuits brought with them made it even harder to move on for everyone involved.Canadian filmmaker Egoyan does not tell that particular story, but a fictional version of it, thereby even upstaging Banks' source material e.g. by adding a recurring spot-on poetical reference that is prone to send shivers down your spine. Also in focus of the film: The tight-knit community and a lawyer trying to help people make a case, resulting in a stirring slice-of-life portrayal of loss and how to cope with it seen from different angles. Tragic figures abound, nobody is spared, among them the lawyer himself (the outstanding Ian Holm), who has to deal with his own unrelated personal loss, or the paralyzed 14-year old survivor of the incident (touchingly played by Sarah Polley) who has to make a serious decision that will affect the whole community. The theme of estrangement, melancholy and helplessness permeates every action, always dominated by the question: How could one possibly get over a tragedy like that? But while the film comes across as sincere and real through the subtle way it was shot, its bittersweet visual poetry will haunt you, and the picture is also bold enough to go for a very powerful, unexpected final statement. "The Sweet Hereafter" is a deeply involving, mature and a thought-provoking piece of cinema and along with "Exotica" among Egoyan's very best.