Solemplex

To me, this movie is perfection.

Glucedee

It's hard to see any effort in the film. There's no comedy to speak of, no real drama and, worst of all.

Hadrina

The movie's neither hopeful in contrived ways, nor hopeless in different contrived ways. Somehow it manages to be wonderful

Payno

I think this is a new genre that they're all sort of working their way through it and haven't got all the kinks worked out yet but it's a genre that works for me.

mark.waltz

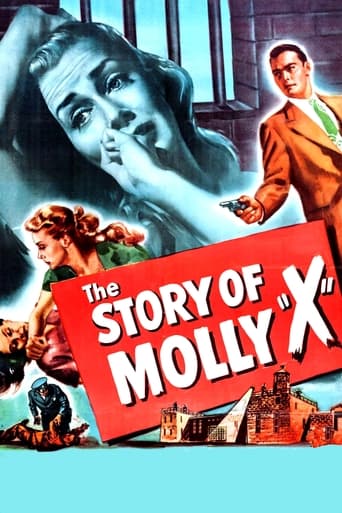

I guess what they are saying here is that women in power who broke the law were getting away with it. Literally, somebody does say that it used to be the case that women weren't capable of running organized crime. June Havoc, aka Baby June, is not your homemaker type, seen in the first 20 minutes leading a gang of racketeers to robbery and murder, and eventually committing one herself. She's sent to a women's prison, and typically, someone is heard saying "Get a load of the new fish!" Clad in mink as she makes her entrance into the fish bowl. The girlfriend of one of her victims (Dorothy Hart) vows to make her pay and sets out to get every piece of dirt on her that she can.While the plot is overly familiar, there are a lot of great lines, and there's even a Christmas sequence to put Havoc into the holiday spirit as she enters the pen. But this isn't the women's prison of "Caged" or the many carbon copies; it's closer to a house of detention where real efforts to reform these girls are utilized. But Havoc's a tough girl and refuses to comply. "I never got over being born", she says, particularly when she spies a convicted killer sentenced to the gas chamber. Surrounding Havoc in prison are such familiar character players as Connie Gilchrist, Ida Moore and Sandra Gould. Moore, still adorable, succeeds once again in stealing every scene, even as a murderess. Havoc, in perhaps her only lead, gives a decent performance, and I can say without a doubt that she's a better actress than her more famous sister. Havoc really allows the guilt and self hatred to consume her character, and that makes her more fascinating as she narrates the story, giving the impression that she is playing a real person. The torture she displays makes this a unique film noir that drags you in as her choice of a life dragged her down.

Alex da Silva

June Havoc (Molly X) heads up a gang in San Francisco that specializes in robbery. The gang includes John Russell (Cash) and Elliott Lewis (Rod), but Lewis has a girlfriend Dorothy Hart (Anne) who is suspicious of Havoc and her intentions towards Lewis. This female rivalry is Havoc's primary danger once she kills Lewis for previously shooting her husband. Havoc is arrested along with Russell in respect of their latest robbery, and while at the police station Charles McGraw (Breen) suspects Havoc's gang of the murder of Lewis, he needs the gun that fired the bullet in order to get a conviction. Havoc and Russell have hidden the gun and Dorothy Hart is determined to get Havoc sent to the gas chamber as she is convinced that Havoc is the one that killed her boyfriend. We follow Havoc and her time in jail, until one day, Hart turns up at the same institution with revenge firmly in her head, even though the murder has not yet been proved.This film cracks along at a good pace. Quite a lot happens at the beginning in terms of robberies and the dialogue gets straight to the point. It's no-holds-barred kind of stuff, especially the dislike between Dorothy Hart and June Havoc. Unfortunately, the film quality is poor, and as much of the action at the beginning takes place at night, even though you know what the gist of the story is, you can't really see what is happening. This is a mark against the enjoyment of the film, I'm afraid - what's the point of staring at a screen on which you can't make out what is going on? The overall acting isn't that good. June Havoc convinces in her tough girl role despite her glamour, while Dorothy Hart is way too glamorous in her prison scenes, yet she is entertaining whenever on screen. Charles McGraw doesn't have much screen time, but convinces whenever he is around. The majority of the film is set in the women's prison (where everyone seems to retain their Hollywood glamour but there is no lezzie action) and there is a twist at the film's finale that is just too convenient for words.

bmacv

Why wasn't June Havoc in more movies? She's probably best remembered, biographically at any rate, as young vaudeville star Baby June Hovick, in Gypsy, who ran off to elope, breaking Mama Rose's heart and leading her to push her shrinking violet of a sister into the spotlight. That wall-flower became society `ecdysiast' Gypsy Rose Lee, who wrote the book for the hit musical and its various compromised film versions. Lee's version of their lives caused a long-lasting rift between the siblings.But Havoc had talent of her own, and plenty of it. She brought style and panache to her role in Chicago Deadline, for instance, and proved a welcome foil to the humorless Alan Ladd. That same year she took the title role in Crane Wilbur's The Story of Molly X, one of the better instalments in the noir cycle that time seems to have lost track of. The Story of Molly X is a surprising work on many counts. It's one of the few (and one of the first) crime dramas to feature a woman as head of a mob (true, Dame Judith Anderson did it in Lady Scarface, but hers was a secondary role). Widow of a Kansas City gangster who was slain (assailant unknown), she's set herself up in fancy San Francisco digs. There's some resentment against her when she summons her gang west to knock over a jewelry-store vault, most virulently from Dorothy Hart, who serves as moll to one of the other gang members (Elliott Lewis). Resentment turns to hatred when Havoc seduces Lewis into admitting he killed her husband, then plugs him for revenge. The planned burglary goes awry, and despite Havoc's belief that the cops couldn't find `a pair of pajamas in a bowl of soup,' she's apprehended (the detective in charge is Charles McGraw). She's sent to Tehachapi for only a short stretch, knowing , however, that if the revolver she ditched is ever found, she'll end up in the gas chamber at San Quentin.Here the script takes an unexpected turn. A year before John Cromwell would make the Sistine Chapel of women's-prison movies, Caged, Havoc enrolls into a Correctional Institution for Women that's as comfy and cozy as the campuses of the Seven Sisters colleges for the brainier daughters of the well-to-do. At first, Havoc plays hard case, refusing even the light work details assigned to her. But confinement to her room summons up some demons from her past: She confides a history of sexual abuse by her stepfather.Now, this may be so much dollar-book Freud in explaining her career in crime, but, in 1949, it was something of a breakthrough. The exploitation of children for sexual purposes was then barely acknowledged, even in most of the psychiatric establishment. Movies like Bewitched or The Three Faces of Eve or Lizzie that dealt with Multiple Personality Disorder – which is widely thought to have its origins in severe physical or sexual abuse in childhood – fastidiously avoided its roots (Joanne Woodward, who won an Academy Award as Eve, contracted it by being forced to kiss grandma goodbye in her coffin). So on that point alone, Molly X deserves credit (as does another movie of the same year that more gingerly hinted at similar shenanigans: Abandoned). Escaping her memories by gratefully returning to work, Havoc shows unexpected spunk and fellow-feeling by rescuing other inmates caught in a laundry-room steam explosion. She turns into a model prisoner, at least until the arrival of a shipment of `new fish' proves to contain none other than her nemesis Hart.. Remember, the murder weapon still remains unfound....Wilbur, both as scriptwriter and director, showed an attraction for stories that dealt with the realities or the aftermath of prison life: Canon City, Outside The Wall, Inside The Walls of Folsom Prison, Women's Prison. In Molly X, he argues the thesis that the penal system is progressive, even enlightened, supplying the rehabilitation that inmates at heart crave. (The antithesis was advanced with dark and persuasive brilliance in the following year's Caged.) He bolsters his argument by means of a none-too-plausible twist at the end. But along the way, especially in the pre-Tehachapi sequences, he shows a real flair for the volatile moodiness of film noir. And in Havoc, who runs the gamut from hard-boiled defiance to contrition as convincingly as the confines of the script allow, he found a star who, for once, got to show just how good she could be.