Exoticalot

People are voting emotionally.

SnoReptilePlenty

Memorable, crazy movie

Bessie Smyth

Great story, amazing characters, superb action, enthralling cinematography. Yes, this is something I am glad I spent money on.

Ben Parker

I was all set to adore this movie. I'd just seen Woman is a Woman and loved it, and the opening 30 mins of this look gorgeous in black and white on Blu Ray. The whispering and close-ups are hypnotic, and the monkeying around is not bothersome. But then, quel disastre, a typical Godard left turn, and I have to sit through (what felt like) 45 minutes of ponderous talking heads. You had to be there. I took years to get around to watching this, and I was loving it, honest, but man, he just wore me down. I had to admit that I was hating it. Just like some boring documentary. Why oh why such extended ruminations. Show not tell that's the idea. In this film its show for 30 minutes then tell for 30. I had to turn it off, sadly. So, my rating reflects this. I loved exactly half of what I saw. 5/10

Chris_Docker

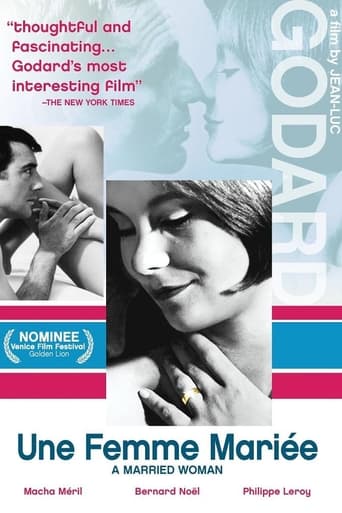

What defines us? Or, what defines anything, for that matter? Is it a dictionary definition or our composite understanding that defines? A Married Woman (Une Femme Mariée) is perhaps better understood with reference to its original title, The Married Woman. Our opening scene is merely two lovers. A Man. A Woman. Photographed with immaculate perfection, shorn of erotic or personal overtones, each shot encapsulates the beauty and symmetry of an exquisite fashion ad – say, maybe, Chanel. Only after a few moments do we find out who these two individuals – impeccably framed by Raoul Coutard – are in real life. Assuming they are lovers, yes, but we find that Charlotte is a married woman. Her lover is Robert, an actor.Just as 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her viewed the world through the eyes of commodification, so does Une Femme Mariée view it through the superficiality of advertising. The usual love triangle of a man and two women is turned on its head by giving Charlotte (Macha Méril) two men between whom she cannot choose. Her aspiration to be perfect is measured in terms of messages sent by 60's women's magazines and other media defining the 'ideal woman' – whose main aim, it seems, should be to please her husband. Charlotte measures the position of her breasts, listens to a record on how a woman can improve her marriage (it consists of vacuous female laughter), and is expert at seeming light while keeping both men on the back foot. She sees herself as an object of desire by both Robert and husband Pierre and practices superficiality to perfection. She also, however, seems far from dim-witted when giving either of them a grilling.It is easy to become divided over this film. One can view it as trite, a Godard cast-off, or one can admire the cinematic poetry, the precision with which it delivers its point and its critique of the institution of marriage. It almost goes as far as to suggest that such emptiness is the lot of 'The Married Woman.' (The title was changed at the censor's insistence, who found the definite article disparaging to French women generally. A topless scene was also chopped.) "I love you too, Pierre. Often not the way you believe, but it's sincere." While men's underwear adverts are just plain photos, adverts for women's lingerie are accompanied by unrealistic promises of what they will deliver in a woman's love life (mostly, of course, in terms of a man's pleasure). At one point, Charlotte is standing next to a gigantic brassiere advert, and it is touchingly clear that society made the image more important than the individual.Each of our main characters has a monologue, but we additionally hear Charlotte's internal monologue. When she has had sad thoughts, she repeats to herself, "I'm happy . . . I'm happy . . . I'm happy," as if the mantra will translate into reality. When she learns from the doctor that she is three months' pregnant (to whom?), her internal voice tells her, "Find a solution . . .. Save appearances." She continues to rely quite effectively on the character she has become, now telling each man how much she loves him, all the while skilfully testing him. It is almost as if primitive instinct to secure a hunter-provider takes over. Although Charlotte admits to the doctor she is scared, she doesn't lose her inner composure even once in the whole movie. She might even be shouting, but we can believe it is part of her dexterous womanish wiles – quite ironic, given that she presses Robert to define acting and say exactly how it is different to real life. Only once does she falter, tripping and falling in the road as she leaves the doctor's surgery. When I look back on a film that is almost devoid of real emotion, it is a heart-rending moment.Apart from intertitles, and jump-cuts to juxtapose intertextual media with narrative, other cinematic tricks include switching between positive and negative photographic images and superimposing summaries. Charlotte eavesdrops on two teenagers as they discuss what a man does during the loss of one's virginity. Salient point appear in small grey letters over the image (for instance, "Je dors avec un garçon"), perhaps showing how Charlotte reduces everything to its minimalist formula. For those that find the film itself as empty as the subject matter, one need only to look at the extended references to Racine (in Berenice, where Racine similarly makes something out of nothing for a similarly helpless protagonist), or Moliere, who answered critics by saying that, to prevent sin, theatre purifies love.Perhaps Cahiers critic Jean-Louis Cornolli summed it up best when he described Une Femme Mariée as "a film about a woman's beauty and the ugliness of her world." Macha Méril credits it with striking a blow for women's rights at a time when the pill was still illegal in France.

MisterWhiplash

We see a hand, then another hand, in the frame of the opening shot of Jean-Luc Godard's Une femme mariee. It's from here that we see a succession of images, all of the body but never anything explicit- a leg, a belly-button, hands, a back, a nude front but covered breasts. Godard is inquiring about the form of a body in and of itself while also trying to find new ways of photographing it. In these shots, which also happen again in this sort of physical poetry a couple of other times in the film, illustrate something both absorbing and elusive about the film in general. It's about form and 'lifestyle, of the married life and the affair, of a bad husband and a tricky squeeze on the side... but then we also have scenes that puncture through the infidelity drama: there's a scene where Robert, the lover, and Charlotte, the main femme of the movie, are sitting in a movie theater at an airport, discreetly, and one wonders what they're about to watch (just before this an image of Hitchcock appears as if Charlotte sees it in the lobby), and it turns out to be some kind of holocaust documentary ala Night & Fog. They leave right away. Too much of a shock, or too much reality? How does the outside world affect these people?We get a lot of scenes of characters just talking to one another, asking questions, sometimes in documentary form. Whether it's really Godard off camera asking the questions and turning it into a docu-narrative of some sort (the old Bazinian logic taken to an extreme that an actor in front of a camera is still in a documentary of the actor acting on camera perhaps), or the characters themselves is kept a little unclear. But this doesn't distract from the dialog and monologues being generally, genuinely intriguing and moving even. There's one scene in particular that I shall not forget easily, no pun intended, when Pierre, the husband, espouses about memory and how "impossible" it is for him to forget, and how rotten it can be for someone who has dealt with real horror (he recalls a story, as his character is a pilot, of talking to Roberto Rossellini about a concentration camp victim and memory and that it made him laugh - again, a very harsh contrast of Dachau and Auschwitz mentioned for interpretation). This and a few other times when characters just go off on something has a lasting impact. Une femme Mariee is filled with the sort of cinematic rhythm that would immediately say to someone unfamiliar with foreign/art-house film, let alone Godard, "oh, that's an 'arty' movie". It certainly is: everything from its themes of alienated characters to its lyrical and original cinematography to the repetition of the Beethoven music (later used in Prenom Carmen) to image itself becomes an issue like when Charlotte obsesses over ladies wearing bras in a magazine, it's all from an artist who expresses his concerns in a my-way-or-the- highway attitude to the audience. And you want to go along with him, if curious enough, to see where he'll take his trio of characters in the Parisian settings. Sometimes there's even weird, dark humor, like when Charlotte finds a random record of some woman in agony and it's the sound of a woman just laughing - something that Charlotte and Pierre listen to in silence until Charlotte wants to put on another record and she becomes like a little kid trying to put it on without Pierre getting in her way. What looks disjointed and without a plot is deceptive when looking at it in pieces. But somehow Godard's film works as a whole piece, and it's part of the point to find this character Charlotte not easy to figure out. The men in her life barely know themselves. And by the end, when it should be about the melodrama of a baby on the way, Godard side- steps this (already dealing with it comically in A Woman is a Woman), by making it about something else on the surface and underneath full of tension. Notice how demanding Charlotte is of answers from Robert about what it means to be an actor. He answers well and stands his ground, but it becomes noticeable that it's not about getting answers on acting or real love but about this woman's tortured self-made life. It's not emotionally gripping, but it gets one to think and it's this that makes Godard's film special in his cannon of great 1960's works.

Wheatpenny

This time there's one female lead choosing between two men, something pretty rare in a medium usually fueled by male fantasies. Charlotte is a young middle-class married woman having an affair with an actor. She has promised her lover she'll divorce her husband, but an unplanned pregnancy makes her question that decision. The film follows her as she attempts to decide between them.Like other Godard films that followed it (Masculin/Feminin, 2 or 3 Things, Made in USA) one of the primary themes here is the extent to which a modern individual's life is manipulated by commercial culture, and how it influences the choices we make. Perhaps because he had yet to fully mature as a filmmaker, this theme is much less subtle here than in those later films. Charlotte is barraged with nonsensical beauty ads and Cosmo-type articles about achieving the "perfect breast size," and in one famous shot is literally dwarfed by a billboard of "the perfect woman" in a bra. The height of social control is reached in the form of an absurd device her lover gives her that hooks around her waist like a belt and sounds an alarm every time her posture slackens. The effect of this visual over-stimulation on her is pernicious. Like the magazine ads we're shown, her thoughts (heard in voice-over) are fragmented and incoherent, indecisive and ultimately meaningless.The other recurring Godardian theme appearing here is the commodification of the female body. To her bourgeois husband, who represents the patriarchal tradition and middle-class status quo, she's more an object to be protected (like the records he brings back from Germany) and exploited (he rapes her when she won't make love) than a human being to be understood. Ironically, his unwillingness to forgive a past infidelity and his possessive jealousy only compels her more to see freedom in a lover. But unlike her husband, who treats her like a commercial object, her lover treats her as a sex object ("Is it still love when it's from behind?" she wonders early in the film) and seems interested only in her body. Her scenes with him are composed of tightly-framed shots of his hand stroking her naked body, shots resembling the photographs selling stockings and bras in her magazines. Her lover literally sees her as a whole person only once, when she goes up on the roof naked. Accordingly, he gets angry, out of possessiveness. Godard's dim view of the condition of modern woman sees her as unable to break free of her past (her husband) due to the self-sufficiency and humanity she's denied in the present. As she ages, a woman's role goes from sex object to status-based commodity, and society teaches her that to think otherwise is wrong. This is a concept still ahead of its time today, when violent, over-sexualized junk like the Tomb Raider movies are sold as female empowerment.As with most of Godard's films, there are always several things going on at once, and this capsule review barely scratches the surface. In the context of his career, the film is best understood as an early version of 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her, which he made three years later and is unquestionably better. By that film, Godard had learned to synthesize his social, emotional, and political themes into one seamless whole, discarding the artificial narrative conventions that serve him no purpose. This one, while no classic, is essential viewing for anyone interested in Godard's progression from brilliant filmmaker to serious artist.