Titreenp

SERIOUSLY. This is what the crap Hollywood still puts out?

ReaderKenka

Let's be realistic.

Tayloriona

Although I seem to have had higher expectations than I thought, the movie is super entertaining.

Married Baby

Just intense enough to provide a much-needed diversion, just lightweight enough to make you forget about it soon after it’s over. It’s not exactly “good,” per se, but it does what it sets out to do in terms of putting us on edge, which makes it … successful?

Robert J. Maxwell

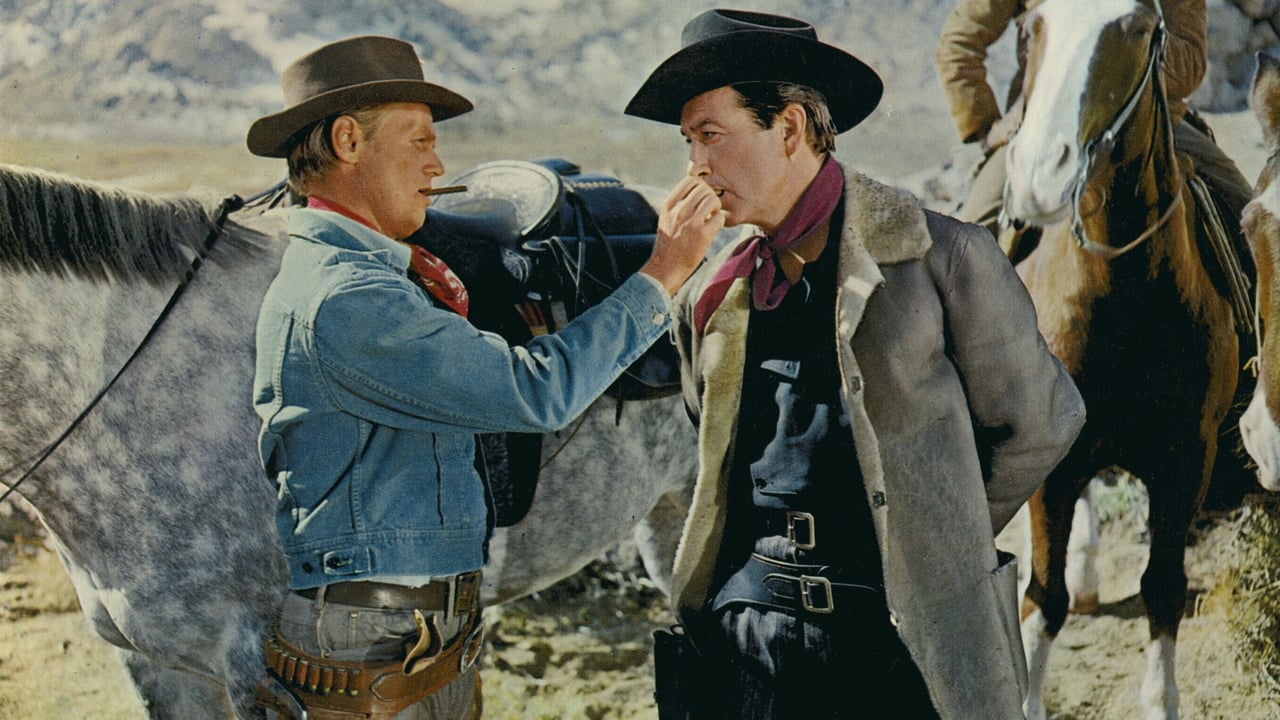

In this Western, Robert Taylor as Jake Wade is the alpha male and wardrobe has dressed him in midnight blue from head to toe except for the silver bullets in his gun belt that function as a kind of accessory. There was a time when Taylor and Richard Widmark rode on the wild side together. Widmark managed to break Taylor out of jail. Now Taylor has ridden miles to do the same for his former friend. After their escape, before they split up, Widmark wears an oily smile. He doesn't seem particularly grateful for what Taylor has done. In fact, the narcissistic Widmark demands to know what Taylor did with the loot from their last robbery. "I buried it somewhere and there it stays." Widmark genially asks Taylor for a gun so he can kill him on the spot. No dice. Throughout, Widmark gives a better performance than the ligneous Robert Taylor, whose default expression is a scowl, but that's not saying much.Taylor rides off by himself and returns to the town where he removes his dark blue pea coat and reveals a dark blue shirt sporting another accessory, the silver badge of a marshal -- or maybe it's a sheriff's badge. I get the two titles mixed up because it never makes any difference which is the correct one anyway. A heterosexual, Taylor has a fiancée in town, the beguiling Patricia Owens, a red head with pupils like big black glistening olives. Over dinner, which is barely touched, as usual in these stories, they have an argument. Taylor wants to get married, pull up stakes, and move farther West, no doubt thinking about that smirk on Widmark's face. Owens sensibly asks why but of course he can't tell her without revealing his miscreant past.Things go from bad to worse. Widmark and half a dozen compañeros show up in town and kidnap Taylor and Owens with the objective of forcing Taylor to take them to the place where the stolen stash is buried. There follows a long journey through forests, over mountains, through what appears to be Zabriskie Point in Death Valley, to the ghost town where the treasure is. There are snide remarks from Henry Silva and some of the other goons about Owens' figure but Widmark is thinking only of pelf, after the acquisition of which he intends to slaughter Taylor and do God knows what with Owens. Of course, Taylor makes some plucky escape attempts but they only prove to be brief delays. Nice atmospheric shooting during some of these scenes. Death Valley is nonpareil. The ragged hills are tinted with lavender. On a chilly September night in Death Valley I stopped the car next to a sidewinder (Crotalus cerastes) who was curled up on the slightly warmer black pavement. He was sluggish enough for me to pick him up by the tail, whirl him over my head, and fling him off into the sand and out of danger.When they finally reach the ghost town, it's beautifully bleachly dilapidated -- only a handful of empty weathered buildings and outhouses, a leaning water tower, a neglected cemetery, disarticulated wagons and other artifacts, and a main street with scattered creosote bush. It's the kind of setting that a child would be delighted to explore. The child probably wouldn't like the fact that the place is surrounded by hostile Indians. The Indians stage an attack that was pretty brutal for its time, but they are finally driven away and all the thugs expect Widmark are killed by arrows. This leave Taylor and Widmark for the final shoot out on the desolate street. Guess who wins. Widmark wins! He ravages the girl, desecrates Taylor's body, ties it behind his chariot, and races around the walls of Troy.

Wuchak

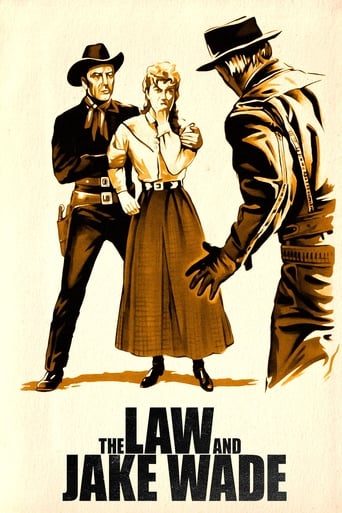

Released in 1958, "The Law and Jake Wade" stars Robert Taylor as the title character who was an outlaw after the Civil War, but is now a sheriff out West. A member of his former gang, Clint Hollister (Richard Widmark), won't let him start a new life and forces Jake and his fiancé (Patricia Owens) to lead him and a few other ne'er-do-wells to some buried money in a ghost town in the mountains. Unlike Jake, Clint is bad through and through and the new lawman is convinced he'll kill him after he gets the money.This Western has a lot going for it: a solid cast, particularly Taylor as Wade and Widmark as the arrogant and no-good Clint (both are convincing Westerners); utterly breathtaking Western locations, shot in Alabama Hills , Lone Pine and Death Valley National Park, California; and some fascinating ruminations on the nature of morality, evil, law, friendship and rivalry.As far as law goes, Clint argues that he killed and looted before and after the war, which society naturally considered evil, but he did the same thing during the war where the South viewed him as a faithful citizen. To him there's no difference, but Jake sees the difference in that the state of war may justify certain actions against enemies that aren't justified otherwise. Furthermore, Jake regrets his outlaw days whereas Clint has zero qualms about the evil that he wreaks.Unfortunately, there are some problems on this front that are never answered. For instance, if Jake is now a "good man" and respects law and order (which explains the movie's title) why does he foolishly break Clint out of jail at the beginning of the movie? It's revealed that he's a man of honor who's paying back a debt, but – by doing this – he releases a serious criminal to continue to commit atrocities. He even admits that he's convinced that Clint will eventually murder him, which means he knows he's incorrigible. Furthermore, in breaking Clint free of his death sentence a few guys get shot during the escape, although not killed. Isn't this a ridiculous risk even if Jake's being honorable by repaying a debt? It's not just a risk of innocent people potentially dying, but Jake's face was undisguised for all to see, which could potentially ruin his new life (more on this below). Everything points to nothing good coming from saving Clint from the hangman's rope but, then again, maybe Jake was holding on to the slightest possibility that Clint would see his good fortune and go straight. In other words, he was hoping for redemption for the man. In fact, it was presumably this very thing that turned Jake around.An aspect about the plot that I liked was the friendship AND hostility of Jake and Clint's relationship. I've experienced one significant relationship like this where it's a close friendship, but with flashes of hostility rooted in the stoo-pid rivalry of the other guy, which he can't seem to deal with. Right now we're on negative terms because I dared to confront him about something he was doing that was wrong and he didn't like it. I'm about ready to call him and say (with a Western twang), "This town's not big enough for the both of us." The main reason I'm not giving "The Law and Jake Wade" a higher rating is because of the contrived nature of certain aspects of the story and some obvious plot holes. For instance, at the beginning Jake enters the jailhouse early in the AM and the sole person guarding Clint doesn't even hear that someone entered the facility until Jake sticks a gun to his back. Why sure! Furthermore, as noted above, Jake doesn't seem to be doing a lot to disguise his identity when the town's a mere 60 miles or so from the town where he's the sheriff. Wouldn't law officers in one town be relatively known in other towns in the general region? So Jake's taking an unbelievable risk in openly breaking Clint out of jail without a disguise (a simple scarf hiding his face would've solved this issue). These types of problems in scripts – particularly old Westerns (pre-60s/70s) – insult the intelligence of viewers and loses their respect. There are numerous 50's Westerns that are guilty of these types of eye-rolling contrivances and plot holes.Nevertheless, there's definitely enough good in "The Law and Jake Wade" to give it a thumbs up, especially the two strong leads, their love/hate relationship and the fascinating explorations of good and evil, law and outlawry, friendship and rivalry. Too bad the film's glaring negatives hold it back from greatness. Still, it's one of my personal favorite Westerns. DeForest Kelley (aka Dr. McCoy) appears in a peripheral role as one of Clint's heavies.The film runs 86 minutes.GRADE: B

JohnHowardReid

When "Bad Day at Black Rock" was released back in 1955, director John Sturges was hailed as the master of Cinema-Scope suspense. Despite a somewhat unconvincing climax (mostly caused by Spencer Tracy's refusal to spend any more time on location, which meant that the scene had to be shot on a studio sound stage), the film was hailed by all as a gem of jeopardy. Certainly Millard Kaufman's taut script and a fine array of support players led by Lee Marvin and Ernest Borgnine helped. Some critics feel that Sturges' abilities gradually declined after this and that he never topped "Bad Day...", but to me "The Law and Jake Wade" proves these suspicions wrong. How brilliantly Sturges uses CinemaScope here to obtain his effects! The very landscapes (and there are a great many of them, thanks to extensive location shooting) seem not only hostile and threatening, but they are made to close in on our protagonists like a prison. The few interiors reinforce this motif. Prison cells and the eerie, cramped quarters of a ghost town are relieved by just one dinner-table scene, which is the only sequence in the movie which doesn't quite succeed. (An ill-judged, distorted close-up of Robert Taylor doesn't help).Perhaps most of the instant-information dialogue in the earlier scenes is a bit too obviously pat, but otherwise the William Bowers script is not only tautly exciting, but offers excellent opportunities to support players like Middleton, Silva and Kelley. In the flashier star role, Richard Widmark pulls out all stops to impress, but I found the less flamboyant, more subtly skilled acting of Robert Taylor more appealing. It's difficult to maintain sympathy as the good guy when you're on the receiving end all the time and your opponent has all the snappy dialogue, but Taylor comes through this ordeal with flying colors. And the writer does relent at the end when he hands Taylor a neat rejoinder to Widmark's aggrieved protest, "I was going to hand you your gun!" Taylor replies: "But then you always liked me much more than I liked you!"

alexandre michel liberman (tmwest)

No question that the end is important to a film but also it takes only a couple of minutes. The last scenes of Jake Wade are too conventional and not in the same level . John Sturges is here at his best with a story full of surprises and with the excellent Richard Widmark . Robert Taylor is Jake Wade, a man driven by guilty feelings. Guilt can lead you to crazy acts and that is what Jake does when he saves Clint (Widmark) from being hanged. Instead of being grateful Clint and his gang kidnap Jake and his girlfriend Peggy (Patricia Owens) and will kill him after he shows them where he hid the money. If Jake would escape from that, would his conscience make him give Clint another chance? Would he make the same mistake he made before? Jake has troubled feelings because Clint had saved him from being hanged in the past. His guilt and sense of fair play will determine his actions.