Holstra

Boring, long, and too preachy.

Dorathen

Better Late Then Never

Solidrariol

Am I Missing Something?

Lollivan

It's the kind of movie you'll want to see a second time with someone who hasn't seen it yet, to remember what it was like to watch it for the first time.

Jackson Booth-Millard

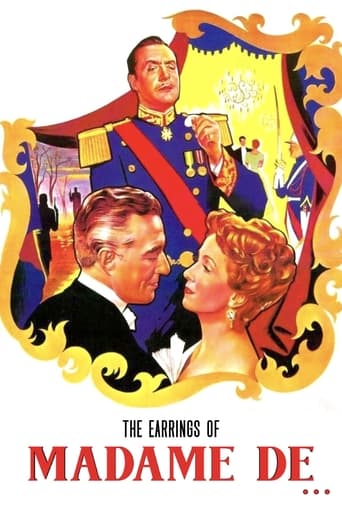

From director Max Ophüls (Letter from an Unknown Woman, The Reckless Moment), also titled The Earrings of Madame De... this French film was one featured in the book 100 Movies You Must See Before You Die, not one I knew anything about, but I was prepared to try it. Basically set in the late 19th Century in Paris, France, a not fully named Countess Louise De... (Danielle Darrieux) is the wife of General André De... (Charles Boyer), and when she has debts that need to be paid the only thing she can do to get the money is sell her earrings. These earrings were her wedding gift from her husband, and without her knowledge the general manages to buy them back again, but he does not return them to her, he gives them as a gift to his mistress Lola (Lia Di Leo). He leaves and goes to Constantinople, and unaware to him the earrings are passed to Italian diplomat Baron Fabrizio Donati (Vittorio De Sica) who buys them, and eventually he goes to Paris where he meets Louise. With him in the picture she becomes much less frivolous and discovers true love, but of course the general will clash between them, to the point where a duel is arranged, and Louise ends up the victim of a gunshot between the men, and the final shot sees the earrings in church in a glass case. Also starring Mireille Perrey as Madame De...'s nurse, Jean Debucourt as Monsieur Rémy the jeweller, Serge Lecointe as Jérome Rémy, his son, Jean Galland as Monsieur De Bernac, Hubert Noël as Henri De Maleville and Léon Walther as Theatre manager. The cast all do their parts absolutely fine, I admit the story of the earrings going from person to person and eventually ending back at the start is intriguing, I couldn't follow everything going on, especially not with the posh period and upper class lifestyle stuff, but the costumes were good, location shots were fine, and some scenes of romance and action were interesting, a not bad drama. Good!

antcol8

Gliding...The inexorable movement - of life.Why talk about "camera movements" - tracks, dollies, cranes - at all, if we're not going to talk about what they DO - what they MEAN.Anybody with enough money can fill their film with dolly shots.The Dance...Of lifeOf deathTrains. Balls and trains.The circularity of a "white lie"The elegance of an elegant ensemble each bringing their own life story to bear on the way they inhabit (and do they!) their roles. You don't need to know anything about this, but the more you know the deeper the film gets.Maybe the key line is when Boyer says to Darrieux "Our relationship is only superficially superficial".Those who need to "identify" with the characters in a film, and thus find that the social position of these characters makes engagement with this film impossible...Well, I just feel sorry for you. Really.I think another read through of a concise cinema book - maybe Sarris' American Cinema - is in order.What does he write about Ophuls? "His elegant characters lack nothing and lose everything."Exactly.But besides all that...Composition and the clarity of the arc. Underneath all of the gliding and circularity, an unstoppable forward motion. Carried through and fulfilled like in very,very few films. The word "Masterpiece" - unfortunate word! - must be used.One word to my fellow IMDb reviewers: I really think the word "boring" should carry the same onus as an unacknowledged spoiler. You are bored? Check yourself.This review has nearly no content, but it is very hard to write anything about perfection.

kenjha

A Parisian countess pawns her precious earrings and lies to her husband that she lost it. The film looks and sounds beautiful, with its opulent cinematography and romantic score. Ophuls' fluid camera work is quite impressive, but he is let down by a routine script that runs out of steam long before the final credits roll. The acting by Darrieux, Boyer, and De Sica is good, although the characters are not particularly well developed. After starting out as a light romantic drama, the film's tone turns rather serious. In fact, it turns into something of a dreary soap opera featuring a tragic love triangle. The contrived ending does not help matters.

WinterMaiden

There is little of praise I can add to what others have said. I would like to address the comments of those who don't like the film because they find Louise unworthy of their admiration or sympathy. (There are two threads on the board that raise the same objection, and one quotes a review that calls her a "dick.")Do you feel sympathy for Humbert Humbert? Or for Emma Bovary? Or for Anna Karenina? Or for the Vicomte de Valmont? People are certainly free not to like the directing style of Max Ophuls or the performance styles of his actors. But in the negative reactions to this film, and especially to the character of Louise, I detect a strong whiff of anachronistic response, and an inability to see the film in the context of its time and place, not to mention the characters in the context of their society. It also seems to me that many people have a sort of high school notion that you have to find a character admirable in order to feel sorry for her. Or, for that matter, that you have to feel sympathy for a character in order to be moved by her story.The irony of "Madame de. . ." is that it turns out that the character with the deepest and most constant emotions is the General, who has concealed the depth of his feelings for Louise because it is not the fashion to be in love with one's own wife. He follows the rules; he has mistresses; he doesn't mind Louise's lovers too much as long she too follows the rules. He can't handle it when she strays outside the lines, and it is HIS behavior, not hers, that finally ruins them all.The art of "Madame de..." is that the lush setting and sense of a society that lives on ersatz emotion prepares us to be caught up in the ecstasy of Louise's immolation as the emotions become real. That doesn't mean that the Baron is really the Romeo to her Juliet, or that (artistically speaking) he needs to be. In her review of "The Story of Adèle H.," Pauline Kael comments on what a pathetically inadequate object of obsession Lt. Pinson constitutes. Indeed, late in the film, when Adèle passes him on the street, she doesn't even notice him. The Baron is also a rather bland love object, and it is true that we have little sense of how far their affair has progressed, or if he would even want Louise to leave her husband for him. (That is not, after all, how the game is played.) In the Garbo "Camille," Robert Taylor's Armand is utterly unworthy of her, and I've never seen a version of "Anna Karenina" where the Vronsky seemed worth ruining oneself over--or who, for that matter, really seemed to WANT Anna to leave her husband for him.Louise's tragedy is that her understanding of the game, of which she is a typically petty and only somewhat skilled player (she has, after all, already skirted the edge of ruin by falling deeply into debt), does not prepare her for actual love. Once there she tries to behave well, but events spiral out of the control of all the characters once they are outside of the predictable game. We don't even have to see a redemption in the completeness with which she gives herself up to her love, or her making herself ill over it; her behavior is by and large selfish and unconcerned with the feelings of anyone other than herself. If not a redemption she does have a kind of saving grace: she doesn't ask for pity or understanding (although she does ask for forgiveness), and she does achieve a kind of understanding of herself when she admits near the end that she is hopelessly vain. What makes "Madame de. . ." a great film, though, is how we see the General, Louise, and even the bland Baron become human as they step outside the rules of the game, and the way in which the art of Ophuls prepares us for the exaltation of Louise's destruction. You don't have to pity her to be moved by the emotion of it. You may even find a dreadful comedy in it, as one does with Humbert. Humbert knows how unworthy he is as a figure of tragedy; Valmont realizes with a bitter sense of irony that he has destroyed himself with his own clever pettiness. Louise lacks those levels of insight, as well as their degree of villainy, but her lack of credentials to be a great heroine is itself moving. At the end, when she finally destroys herself, it seems to be, at last, in her first more-or-less-selfless gesture-- ambiguous, though, as everything in Ophuls is. Perhaps Renoir (the allusion to him above being deliberate) could have made these characters more sympathetic, or made us feel more tenderness for unsympathetic characters. (Renoir could make us feel tenderness for a rock.) But Ophuls is not as purely focused on the human heart as Renoir; he always sees the absurd social animal, as well. I think it is more appropriate with Ophuls to have that distancing, as we have when we read "Madame Bovary."