phd_travel

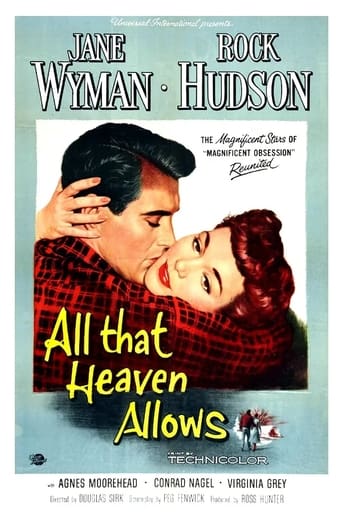

Jane Wyman stars a wealthy widow in a conservative town and Rock Hudson stars as her much younger gardener who falls in love with her. As the relationship progresses she faces a nasty town gossip, disapproval from the friends at the club and finally the non acceptance by her children.Quite insightful movie with some clear powerful messages for it's time. When a movie is good it doesn't feel dated even though the fact of dating a younger man nowadays is slightly less taboo the sense of ostracism for having a different relationship is still relevant today be it due to race gender or religion.Liked the part where after making the sacrifice for her kids it turned out the kids didn't really care later on and she realizes she didn't have to sacrifice after all.The cinematography is pretty.Worth a watch.

Kirpianuscus

after so many time, it is a challenge to define the source of seduction for this real beautiful film. sure, many explanations are reasonable. the romanticism, the performances, the delicate love story against everything, few scenes who are more than magnificent, the basic truths in the right light. but this is only the first step for admire a drama about the need to be yourself. about the essence of happiness. and about the fight for it. short, a film who represents a precious experience.

funkyfry

Director Douglas Sirk takes a story by the obscure writing team of Edna and Harry Lee, puts it together with two big stars in Jane Wyman and Rock Hudson, and emerges with a first-rate critique of the class prejudices and soul-crushing expectations in Country Club America. There aren't many surprises along the way, really, but the thing doesn't just sit there either.... if we, the audience, are allowed to come up for air, then we would lose some of our identification with the superficially "unimportant" tribulations of the heroine, Cary (Wyman). As for Hudson's character (Ron), he doesn't just read, but lives, Thoreau... yes, a character in the movie actually says that. Let's not pretend the movie is any more subtle than any of Sirk's other work.We could pick it apart for all its "unreality", but in my opinion the film was never designed to be real. It's a sort of expressionist take on American culture, one which Sirk would follow up with even more broad strokes on the subject in following years. I do think that the film's discussion on class division would have more weight if, for example, Ron's supposedly rustic hideaway didn't look like something out of Woman's Home Companion's winter guidebook. The Ron Kirby character is a bit too far out of the realm of reality, perhaps because his persona had to be twisted in such a way to make him totally acceptable to the types of people in the audience who might, in their day to day lives, represent the characters in the film who reject him on social grounds. So, it's all very harmless, and when we meet Ron's working class friends they come complete with the friendly Greek fisherman, bird-watching old lady, etc. One wonders what the effect would have been, for example, if one of Marlon Brando's early 50s characters had walked through the door.But again, let's never mind "reality", and let Sirk have his own little pretensions. My main real criticism along those lines is that the film did not show any kind of social pressure coming from Ron's friends against his settling with Cary. Indeed, Ron's best friends (played by Virginia Grey and William Reynolds) are practically gurus of philosophy and tolerance. In actuality, it is not just the rich who perpetuate class division in America. Not to mention, the fact that she was obviously approaching 40 and already had children would have made her an unacceptable wife to many of his young friends, or so we might imagine. The film steers clear of any such criticism and as a result it's take on class (and age-ism) in America is lop-sided.The most cunning and memorable shot in the film is, of course, the one with the TV set turned into a mirror of Cary's loneliness, after she has succumbed to social/family pressure and ended her relationship with Ron. It deserves praise, but Sirk does not just fashion memorable images, but convincing scenes: often, from the most conventional and predictable situations. For example, the big party thrown by Cary's friend Sara (a fire-redhead Agnes Moorehead) -- everything about the scene is already known to the audience; we've seen it in a dozen films. What makes this one memorable is the depth of sleaze to which Donald Curtis' character descends, and his drunken self-conviction. Cary was a tramp all along, he figures, and it's his male prerogative to assume that he can now take her whenever he pleases. As Ron and Cary leave, we hear a voice from amongst the crowd telling us that poor Harvey (Curtis) was fortunate to survive an encounter with such a beast as Ron! It's a better film than it deserves to be, and credit can go to a very solid cast being directed with purpose and intelligence by Sirk.

G K

A sad widow (Jane Wyman) falls in love with the gardener (Rock Hudson) at her winter home, and marries him despite local prejudice when she returns home.All That Heaven Allows is a standard tearjerker in the tradition of Magnificent Obsession (1954), reuniting the same stars, producer Ross Hunter and director Douglas Sirk. At the time, critics failed to grasp the suggested gay subtext in the story, and dismissed it as a routine soap. But modern audiences get the point, through its atmosphere of barely suppressed hysteria and the framing of Wyman as a prisoner in her own home. In 1995, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".