BootDigest

Such a frustrating disappointment

HottWwjdIam

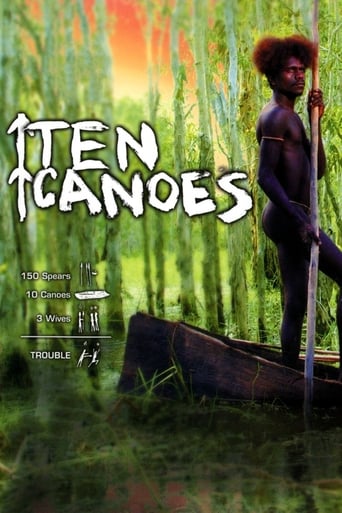

There is just so much movie here. For some it may be too much. But in the same secretly sarcastic way most telemarketers say the phrase, the title of this one is particularly apt.

Lollivan

It's the kind of movie you'll want to see a second time with someone who hasn't seen it yet, to remember what it was like to watch it for the first time.

Allison Davies

The film never slows down or bores, plunging from one harrowing sequence to the next.

sharky_55

For a country whose notion of Indigenous Aboriginal culture comes up to The Dreamtime and dot paintings, Ten Canoes might well serve as a lovely refresher course, never mind how Hollywood might react to it. Growing up I recall being fed healthily on these stories as part of an ever-enthusiastic brand of multicultural education, and relishing them because it was easy for even kids to imagine how the ancient storytellers had come to these conclusions by simply looking around them and rewinding. How the stars in the night sky are camp fires burning brightly to guide hunters home, how the rivers are water goannas larger than you or me could ever comprehend, or how the great emu losts its wings because of its own arrogance and pride (Icarus being just pipped on that one). Another tells the story of how the kangaroo was bestowed its pouch because of the kindness it showed towards Byamee, a god disguised as a troubled wombat. What these stories, and what Ten Canoes shows us, is that even as many millennia separate us, our inherent laws and practices are guided by a karmic belief of cause and effect, often with wry consequences. Fair is fair; the universe ensures that you will always get what is coming to you, and it isn't afraid to get creative. Who better to champion the oral traditions of the Indigenous Aborigines than David Gulpilil? He is without a doubt the most mainstream and well-known of the Aboriginal actors, and retains a delighted curiosity from his first ever screen- credit way back in Nicholas Roeg's masterpiece, Walkabout. In that he played a young boy on the eponymous rite of passage, who positively gurgled when asked to demonstrate his knack for finding water in barren desert, and channeled this fevour elsewhere in his mating dance. Gulpilil has lost none of that fresh-faced charm, and although we cannot see his grin, it is easily identifiable in his narration. It is not quite Attenborough; the storyteller observes with an all- seeing eye, but is not afraid (as we might suspect) to insert his own footnotes here and there, and sometimes chuckle along. Rolf de Heer alternates black-and-white and colour stock as if to mimic dusty old storybooks (if they had they kept them) being brought to life orally, and Gulpilil can't always bear to remain impartial. Which is how most of us like our stories told, with a dash of flavour and colour. de Heer uses the visual as a way of representing an age-old reverence for the land. The Aborigines were nomadic hunters and gatherers, never taking more than necessary, and ensuring that the land too could live and breath beneath the soles of their feet. The cinematography is almost sensual; the camera snakes steadily around tangles of bush and grass, like the hunter making his slow advance, or glides serenely, as if it was also balanced on the canoes the men themselves craft out of tree bark. The water's mirror must not break, the ever-constant buzz of the outback unable to be interrupted. At times it simply lingers, and we see how the landscape twitches, and shimmers in the heat. The story is in fact three stories within one another, of one narrator performing for the gathering around the camp fire, and another using a fable as way of caution. So there are thousands of years connecting the story strands, and the film decides to strengthen them using first and foremost humour, and through showing how it has not aged a day from the past. Fart and dick jokes are means of confronting the modern audience, to force a connection that has not been recognised until this moment. And then we see how their morality system has manifested from lifetimes of incidents and misunderstandings. This is a little further from our own comfort zone, a ritual of justice where spears are thrown until the guilty is wounded. So it is shocking when the conclusion, somehow, manages to make sense: "We've speared your man," says one tribe to another, who respond "who speared ours". Perhaps it is Byamee's way of pushing responsibility towards Yeeralparil, who makes the costly error of lusting after his brother's three wives, and through cruel fate, finds the pleasure turned into burden suddenly thrust onto him. We may not subscribe to the spear for a spear ideology that they practised long ago (indeed we have better method not available to them), but somehow we keep making the same mistakes, and punishment happens to chase us out eventually. And yes, we are still prone to laying around all day and eating honey, although we have made an efficient business out of it. The belly laughs when we are caught with sticky fingers still sound the same.

mukava991

"Ten Canoes" resembles a National Geographic documentary with dramatic overtones and is sometimes hard to follow due to the thick accent of the narrator but it's nevertheless absorbing due in part to its very oddness, being a story about aboriginal Australians (though written, directed and shot by a Caucasian team headed by director Rolf de Heer). Structurally it is a story within a story about a how a tribe in the pre-colonial period handled the sudden disappearance of one of its female members. The story allows de Heer to illustrate how members of this primitive community were not so very different from ourselves in their essential human characteristics. The mere placement of a group of naked, primitive people as central characters in a fictional motion picture drama is, to Western eyes, enough to command the attention. The more or less constant narration tends to hinder dramatic development so that we never connect deeply with any of the characters yet we empathize with their predicaments. Generally speaking, it paints a sympathetic picture of a people whom fate has brutalized and who now are only beginning to recover and get back a sense of who they are and what they come from, in part through films like this one.

bandw

This story begins with an aerial flyover of Arnhem Land in northern Austalia. A narrator comes on saying that he is going to tell a story, his story. His story starts with the recounting of a tale about his ancestors of a few generations back who are making canoes to traverse a crocodile-filled swamp in search of goose eggs. Within that tale a wise older man is telling another, somewhat parallel, tale to his younger brother dating back many generations to "the ancients." In a clever plotting device the ancestor's tale is shown in black and white while the ancient's tale is shown in color. This technique has the dual effect of allowing director Rolf de Heer to duplicate scenes from black and white photographs taken in the area by an anthropologist in the 1930s (photographs that motivated the making of this film), as well as helping the viewer keep the stories straight.The cast consists of a few dozen modern day aboriginals playing the parts in the two stories. They try to capture the reality of the times portrayed, and you can believe that this was the way it could have been thousands of years ago for a tribe of early humans. The earlier Astralians have their own customs and language and the cast speaks in their native language, with English subtitles. I kept thinking of how the basic emotions driving the stories are still with us--fear, jealousy, lust, love, trust, distrust, pride, humor, courage, loyalty, honor. The culture presented is indeed not mine, but it is perfectly understandable. Sorcerers keep the tribe stirred up and mystified with special knowledge of "magic," just as modern religions do (with equal effectiveness). There are laws that must be obeyed, even if unwritten. The young men relish showing prowess in hunting and war making. A creator is deemed the prime mover. Marital relationships are not always harmonious, especially if polygamous. And so on. It appears that no matter how it manifests itself a culture will wrap itself around basic human emotions and desires. It would not be a stretch to recast these stories in a modern setting.The photography of the landscape is beautiful and sensuous; it contributes greatly to the stories by showing what an intimate relationship early peoples had with the land and its fauna.This movie helps us better appreciate where we came from and what we are.

James Hitchcock

There have been a number of films made in Australia about the country's aboriginal population, such as "Walkabout", "The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith" and "Rabbit-Proof Fence", but those all concern relations between Aborigines and white Australians. "Ten Canoes" does something different by telling a story set in Australia's aboriginal past, before the first white men arrived in the country. All the actors are Aborigines, and the dialogue is in the language of the Ganalbingu tribe from what is today Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory.The structure of the film is quite complex, and makes use of what is called in German "Rahmentechnik", or framework technique, the setting of a story within a story. As the two stories are similar they are differentiated by using colour photography for the main story and black-and-white for the "frame". In the framework story, ten men from the tribe are on an expedition to hunt for the eggs of the magpie geese. (The title is taken from the ten canoes in which they travel). One of the young men, Dayindi, is in love with one of the wives of his elder brother Minygululu. (The tribe practise polygamy). This threatens to cause friction between them, but Minygululu tries to defuse the situation by telling his brother a cautionary tale from the "dreamtime", the legendary aboriginal past, about two other brothers in a similar position.The two brothers in the main story are called Ridjimiraril and Yeeralparil. (To provide unity between the two stories, Dayindi and Yeeralparil are played by the same actor, Jamie Gulpilil. His father David, well-known from films such as "Walkabout" and "Crocodile Dundee", acts as the film's narrator). Ridjimiraril has three wives, and Yeeralparil, who is unmarried, is in love with the youngest, Munandjarra. When Nowalingu, one of Ridjimiraril's other wives, disappears, he is convinced that she has been abducted by another tribe, and he kills the man he believes responsible. To avoid all-out war between the tribes, Ridjimiraril must undergo an ordeal in which he tries to avoid spears thrown at him by his enemies, and Yeeralparil must join him in this ordeal. When Ridjimiraril is killed, Yeeralparil, as his younger brother, is obliged under tribal law to marry all three of his wives, not only the beautiful Munandjarra but also Nowalingu (who has returned to the tribe and, it turns out, was not kidnapped at all) and the third wife Banalandju, neither of whom he really fancies.The narrative structure of the film may be complicated, the underlying folk-tale-like story is a simple one. Although a hunter-gatherer culture like that of the Aborigines may be very different to our own, many of their preoccupations are the same as ours- not just physical needs like eating and sex, but also more abstract concepts. The ordeal by spear may seem strange to our eyes, but it is rooted in ideas that are familiar to us- law, justice, and the need to set limits to revenge in order to prevent blood-feuds or the outbreak of all-out war. (If only Bush and Saddam could have settled their differences by throwing spears at one another).Despite some serious themes- love, jealousy and crime and punishment- there is a lot of humour in the film, much of it bawdy- it contains the most memorable fart jokes since Mel Brooks's "Blazing Saddles"- or at the expense of the characters, especially Birrinbirrin, the corpulent tribal elder whose great pleasure in life is eating honey. The cast all play their roles with great naturalness and sincerity. Another important feature is the beautiful photography of Arnhem Land- not the dry, barren outback that normally comes to mind when we think of Australia, but a much lusher, more fertile tropical landscape. The result is a poetic and haunting film, quite unlike any other, which acts as a window into a culture with which few people outside Australia will be familiar. 8/10