Gizmo

Really, this deserves higher than a score of eight, for it is just about everything you really need from a film - an original tale with something to say about the human condition told creatively and powerfully. Michel Simon is of course perfect, and so far ahead in realism than almost any other actor in early sound cinema. The only real flaws in it are a few patchy moments of low sound recording and the sluggish pacing of scene transitions, which seem more to belong to the earlier silent era. Because of this there is a certain creakiness to the film but I find this really only adds to the charm, since it reminds the viewer that this is one of the first French sound movies ever, and a couple of years earlier the very medium itself didn't even exist.

ElMaruecan82

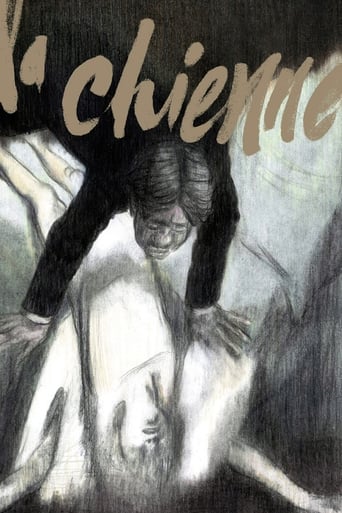

The film opens with Guignol theater à la "Punch and Judy", the first hand-puppet presents a tale of social relevance, the second interrupts him by stating that this is a story making a moral statement about men's behavior but they're all contradicted by the third one, the master of ceremonies who insists that there's no hero, no villain in this story, it's just a sordid "love" triangle involving a "He", a "She" and "The Other Guy": a streetwalker named Lulu (Janie Marese), her boyfriend-pimp Dédé (George Flamand) and Maurice Legrand, the sucker, played by Michel Simon. What a gallery painted in black and white and infinite shades of human complexity by the great Jean Renoir, son of painter and impressionist pioneer Pierre-Auguste Renoir.Maybe like his father, Renoir cared more for 'impressions' than actual realities, there are no villains not because they don't exist but because the perception is so fuzzy in the first place and the roles are switched as the plot moves forward, Legrand is a meek bookkeeper and Sunday painter of intellectual superiority but mocked by his peers and constantly bullied by his wife, a nagging and controlling shrew reminding him everyday that he's not the soldier hero her late husband was. Legrand has surrendered to mediocrity until he fell in love with Lulu, a light of hope. He took her as a muse while she was a leech, sucking out his love, dignity and money for her domineering pimp. Not personal but strictly business, unless by 'personal' we mean that she did it because she loved Dédé. That everyone is driven either by money or lust foreshadows the dark shortcomings of the film, the notion that everything has a price, and they'll all pay for their actions.But again, there's no morale. This is just entertainment, a story starting upon the little theater of Paris, like so many others, we're not here to judge anyone but to witness the flow of events that will cause many people to act one against another acting according to their inclination toward greed and lust. This is the year 1931 and while not a revolutionary story, under the confident directing of Jean Renoir, you come to question why it is Orson Welles' "Citizen Kane" that is regarded as such a revolutionary film, even Welles would give Renoir the credit he deserves. The French director emphasized that "noir" syllabus in his name, with a main character who's resigned to a life of relative weakness to such a point it could almost pass as courage or wisdom, and that strength could only be expressed in awkward and disastrous ways.Played by Janie Merese, Lulu is the pioneering femme fatale, a speaking version of the Woman from the City in Murnau's "Sunrise". But Renoir, almost defensively, claimed that all he wanted to do was to explore a film about a Parisian streetwalker, a job as respectable as any other because he was always fascinated by prostitutes, in a sort of naturalistic move à la Zola. And he also wanted a vehicle for Michel Simon who was then the rising star of French cinema. By making "The Bitch", he struck the two birds with the same stone and made a masterpiece for the ages, that would later be adapted by Fritz Lang in "Scarlett Street" with Edward G. Robinson.But while Lang accentuated the pathos, Renoir conceals the darkness and keeps a certain distance toward the characters, as if he didn't want to overplay the feelings, there's not much pathos in the film, there's even a fair share of comedic moments, as if the whole thing was just tale of tragicomic intensity. He knew the acting of Michel Simon would carry enough emotions not to insist upon them and for his first major talking film, he wanted enough material to explore the actor's versatility. It is ironic that their following collaboration would explore the other side of the coin. Indeed, as Boudu, he'll play a larger-than-life optimistic man who rises above his modest condition because he's just too self-confident.That's the power of Michel Simon who defines the most extreme sides of cinema and can take you from pathetic to sympathetic in a blink of his deformed eyes.I must admit I enjoyed Boudu a little more maybe because cinema, for its spectacular debut, needed such grandstanding characterizations, of histrionic waves but "The Bitch" is a superior film, technically and visually. Maybe it is too dark and modern for its own good, no matter how hard Renoir tries to tone it down. Or maybe the knowledge of the tragedy that surrounded the film created an unpleasant bias. Janie Marese died the night of the premiere, in a car accident. In real life, Simon loved the actress who loved Flamand, as lousy a driver as a boyfriend in the film, he wanted to drive his first car and impress his sweetheart, talk about reality being stranger and crueler than fiction.Michel Simon later fainted in the actress' funeral, threatening to kill Renoir because he "killed" her. That's how much passion was injected in the film, the people were liars but they were sincere.What a tragic irony that fate revealed itself as ugly and twisted and wicked as the story, working like an antidote against criticism. These things do happen after all and life came to the rescue and give it a taste of tragic credibility, besides cinematic prestige.

Hitchcockyan

Jean Renoir's LA CHIENNE is an exhilaratingly nasty tale of a henpecked hosiery cashier's adulterous relationship with a manipulative prostitute, and the moral damnation that ensues. Noir aficionados will instantly make the SCARLET STREET connection but the unmistakable differences in execution and style render both of these masterworks sufficiently distinguishable.Firstly, LA CHIENNE is more sexually charged of the two - evidenced by the explicit exhibition of its various on screen dalliances. SCARLET STREET on the other hand was shackled by the Hays Code where the furthest Edward G. Robinson's character gets is painting his mistress' toe nails. Restrictions of the production code notwithstanding SCARLET STREET is still the bleaker of the two and remains one of the hallmarks of classic film-noir, while LA CHIENNE benefits from its consistent tragicomedy tone.Michel Simon is outstanding as the frustrated, love-struck painter who's almost destined to lose: he's domineered by his miserable wife when he's not being cuckolded and scammed by his deceitful mistress (and her scheming pimp boyfriend) and remains oblivious of the fact that he's merely a part-time lover but a full-time benefactor. EGR's rendition however was on a completely different level and had more psychological heft to it.LA CHIENNE's visual aesthetic is loaded with quadrangular, window-framed, canvas-like compositions that not only resonate with the film's theatrical opening but also with the art produced by our protagonist. I also feel that it's too beautifully realised (or at least the restoration made it so) to be categorised as "noir" in the traditional sense and is devoid of conventional noir flourishes, rugged edges or pulpy vibes. Having said that it was undoubtedly instrumental in the proliferation of films that would come to be known as noir.As an interesting aside, SCARLET STREET was not the only Lang venture that shared a literary source with a Renoir film; HUMAN DESIRE and the classic LA BÊTE HUMAINE also originate from the same Émile Zola novel.

timmy_501

By 1931, Renoir had completely abandoned the innovative superimpositions and wild set designs that characterized his silent films. In La Chienne, he favored a stripped down, almost austere form of realism; nearly every shot in the film is taken from a medium distance and the camera movement is utilitarian. Even the compositions offer few surprises, though one shot neatly emphasizes a character's reaction to his lover's betrayal by detaching the perspective and filtering it through various obstructions. The stripped down style Renoir employs in the film brings the focus to the plot of the film, which involves an old fashioned, wholesome man who is mocked and taken advantage of by everyone he encounters. Eventually, this influence corrupts him totally and he joins the dregs of society. This happens gradually enough to make his transformation believable and genuinely shocking. It also suggests that society is rotten to the core, an idea that it has in common with the Naturalism movement, of which earlier Renoir efforts Whirlpool of Fate and Nana are obviously a part. Although it's tempting to read the film as a misogynist work, especially given that the title translates to The Bitch and that both of the major female characters are absolutely detestable, it's important to note that most of the minor male characters and especially the pimp are equally as reprehensible as either of the two women. In fact, the only character who is treated with much sympathy is the protagonist Legrand and even he ultimately falls from grace. Although Renoir would later gain a reputation for his humanism, this film's portrayal of humanity is as dark as they come.