Christopher Reid

Kagemusha is really gorgeous to look at, like most Kurosawa films. The costumes and sets are impressive and the locations are nice. The imagery is primarily made up of the aftermath of battles and seated discussions. He seems very patient - he will not compromise his artistry to try to keep an audience's attention. Thus, parts of this movie can feel slow. But by the end, once you understand what it's about, I feel it was all very enjoyable. Why should movies have to rush through their plot points? Why can't we admire the scenery and dwell on some thoughts and feelings before moving on?The main character is a thief that looks remarkably like "The Mountain", the head of the Shingen army. This group is in competition with 2 other clans. The leader becomes fatally ill and thus this man is made to be his double for some time. This avoids panic and keeps the enemies intimidated as they believe The Mountain is still alive.Both roles are played Tatsuya Nakadai. He says a lot with his eyes. Sometimes expressing confidence and jocularity, sometimes looking haunted and fearful. The thief initially remains petty and uncooperative but is eventually affected by the aura of the man he is replacing. Perhaps he does gain some real power simply through his appearance, especially if dressed up and in public. He's a bit like a scarecrow. It's quite surreal for him to sit in the position of power, quietly trying to avoid giving anything away. Those that know the secret are emotionally affected by his similarity to The Mountain. And for those that don't know, he has as much power as they grant him.By the end we feel he has been deeply affected by his experience. Maybe his life started to mean something. But that period of usefulness will not last forever. What is he meant to do after that? Kagemusha has plenty of food for thought. And it gives you the time to admire its story, characters and images. I'm not sure I yet fully appreciate the potential meaning of Kagemusha. But I'll remember the little man who unexpectedly became the centre of attention and affected history.

tieman64

"Do not fear when the earthquake comes, and the mountain falls into the sea." - Psalm 46:2On December 22nd, 1971, Akira Kurosawa slid his body into a bathtub and slit his wrists with a blade. He was hospitalised and recovered several weeks later. Biographies differ on how many times Kurosawa slashed himself, but most agree that the 1971 incident was the last of at least a half-dozen other attempts at self-harm or suicide. Why did Kurosawa want to kill himself? Biographies typically offer a cocktail of explanations: depression, existential crises, a family history of suicide (his brother committed suicide in 1933), the critical and financial failures of his recent films and so forth. Whatever the reason, one thing remains clear: the once mighty director had been dethroned, humbled and so forced to reassess his powers, position and life.Similar themes run throughout Kurosawa's "The Shadow Warrior". Released in 1980, it stars Tatsuya Nakadai as Takeda Shingen, a Japanese warlord who rules during the Sengoku period (1460s - 1600s). Nicknamed "the mountain" ("A mountain does not move," Shingen tells his generals), Shingen is feared by all rival warlords. They perceive him as being omnipotent, omniscient and omnipresent. His presence looms menacingly over all of central Japan.But Shingen's begun to confront his own mortality. Making preparations for his death, he's arranged for body-doubles to take his place should he die in combat. These doubles are designed to stave off death, to preserve Shingen, to offer him some semblance of immortality in the face of a Nature expert at dethroning arrogant humans. But will they work?Midway in "Shadow Warrior", Shingen is killed by a sniper's bullet. Kurosawa films this sequence like a police procedural, Shingen's rivals attempting to ascertain how one of their own snipers – a lowly moral – proved capable of downing a God like Shingen. Hilariously, even when all indications point to Shingen having been killed, these rival warlords refuse to believe the evidence. Afterall, mountain's do not fall!Odd for an epic about warlords, "The Shadow Warrior" thus concerns itself not with combat, but with espionage. Every warlord in Japan is busy sending out spies, each desperate for irrefutable evidence that Shingen has fallen. These warlords become increasingly uncertain when Shingen's doubles and generals begin launching attacks on rival kingdoms. Are these attacks proof that Shingen is still alive? Why would Shingen's generals attack others without a mountain on their shoulders?Before he died, Shingen provided his generals with clear instructions: should he be killed, they are to cease attacking rival kingdoms and focus instead on territorial defence. Whilst Shingen's tactical conservatism baffles his generals, they make increasing sense to Kurosawa's audience. Afterall, if the mountain has proved to be fallible, why risk further losses by attacking rivals? More importantly, if all previous certainties have revealed themselves to have rested on sheer belief, on sheer shared delusion, then what other assumptions might be toppled?These issues of "belief" become the chief theme of Kurosawa's final act. Here Shingen's men hold fast to their insane convictions; they are invincible, they are mountains, they are Shingen incarnate, they tell themselves. But of course they are not. And so frauds, impostors, doubles and soldiers die on a battlefield, hundreds slaughtered, arrogance giving way to defeat, egos giving way to death. "The fifty years of a man's life are short compared to that of this world," a character tells us. The film then ends with the corpse of Shingen's double floating down a river. Floating with him is the banner of Shingen's kingdom – the Takeda flag – which speaks of mighty rivers, winds, fires, mountains and soil. These entropic certainties ironically counterpoint the film's frail corpses. In "The Shadow Warrior", downfalls greet all kings, clans, directors, actors and men. To think otherwise is folly. And if to behave differently is fraudulent, all men are impostors."The Shadow Warrior" is the first Kurosawa film that might be termed "Brechtian". The sentimentality and more populist aspects of Kurosawa's previous works are replaced with a distant, dispassionate tone, and most sequences are filmed with stagnant medium and long-shots. Elsewhere metaphysics takes precedent over motion, Kurosawa asks us to examine and ponder the subtleties of each scene, and all characters are held at distance, such that they become faintly absurd. Kurosawa would resurrect this style for his 1985 masterpiece, "Ran", an epic to which "The Shadow Warrior" is often unfairly compared. "The Shadow Warrior" may be flawed – it becomes repetitive, its bloodbaths are oft cheesy rather than profound, and filming in modern Japan forces Kurosawa to rely on claustrophobic exterior shots which hamper the philosophical scope of his picture – but it is nevertheless peppered with many masterful moments. Famously, the film was executive produced by George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola, who convinced 20th Century Fox to make up the shortfall when the film's original produces, Toho Studios, proved unable to afford the film's completion.8/10 – Worth multiple viewings. See "Ran", "Barry Lyndon" and "The Red and the White".

dee.reid

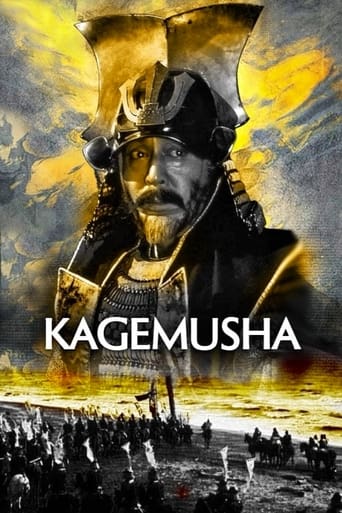

Akira Kurosawa's 180-minute, 1980 "comeback" film "Kagemusha" is one of the director's most ambitious films. Like I already stated, it clocks in at 180 minutes, but the film is never once boring. Having watched his later "Ran" (1985) yesterday and then having watched this movie today, "Kagemusha" is very much a "dress rehearsal" for "Ran" since it can be seen that many ideas/themes from this film were later used on "Ran." (Having watched both movies, however, I can conclude that "Ran" is the better movie.) "Kagemusha" (which means "shadow warrior") and is set over the course of a two-year period between 1573 and 1575 in Japan, concerns a petty, unkempt thief (Tatsuya Nakadai) who is plucked from imminent execution to be the double for the 16th-century warlord Shingen Takeda (also played by Nakadai), due to his striking resemblance to him. When Shingen unexpectedly expires, the thief is forced to take his position as leader of the Takeda Clan. This could have been an amusing comedy, but Kurosawa was too smart for that, and his scope of the material went way beyond what would typically be silly Hollywood comedic theatrics, like a comedy about role-/body-swapping (even though Kurosawa sought financial backing from American filmmakers George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola - two well-known admirers of his from the United States who are also well-known admirers of his impressive body of work over the decades). The main theme of "Kagemusha" is the battle between illusion and reality: The Double effectively deceives a great many people with the illusion that he is the real Shingen (including his grandson, mistresses, and sworn arch-rivals), and the real Shingen's generals (including his brother Nobukado - played by Tsutomu Yamazaki - who also bears an uncanny resemblance to his late brother) must keep up the elaborate charade - while also somehow managing to keep The Double out of trouble and keep away anyone from discovering their ruse. The film ends with an epic, large-scale massacre marking the downfall of the Takeda Clan, but the magic there is that we never actually see any real combat. Instead, we rely on the horrified reactions of the characters as they witness the unrelenting bloodshed of battle. It's a truly powerful moment in a film that never ceases to cause wonder and stir up strong emotions about the enormous "responsibilities" that come with such elaborate deception and the swift fall from power.10/10