SparkMore

n my opinion it was a great movie with some interesting elements, even though having some plot holes and the ending probably was just too messy and crammed together, but still fun to watch and not your casual movie that is similar to all other ones.

Ketrivie

It isn't all that great, actually. Really cheesy and very predicable of how certain scenes are gonna turn play out. However, I guess that's the charm of it all, because I would consider this one of my guilty pleasures.

AnhartLinkin

This story has more twists and turns than a second-rate soap opera.

Kodie Bird

True to its essence, the characters remain on the same line and manage to entertain the viewer, each highlighting their own distinctive qualities or touches.

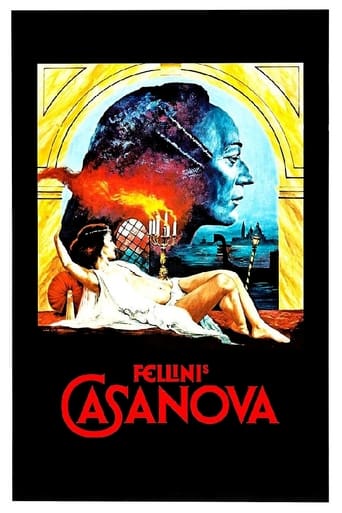

ElMaruecan82

What happens when an extravagant filmmaker makes a movie about an extravagant individual? Well, you obviously reach the height of extravaganza… but is there anything obvious with Fellini? It starts with the title: why this juxtaposition of the two men's names? "Fellini Roma" made sense as it was the vision of a city from one of his sons, Fellini, not Visconti, De Sica or Risi. But Giacomo Casanova is a historical figure, a literate adventurer who wrote exhaustive memoirs (of undisputed authenticity) that became remarkable accounts of the 18th century customs whether in court or… intercourse, why should Casanova then be linked to Fellini as if he was belonging to him? The reason is actually startling, Fellini didn't like Casanova, he took him as a self-centered pompous aristocrat who disguised his crass appetites under an efficient mask of sophistication… so the Casanova we see is the Casanova according to Fellini's vision and Fellini is such a larger-than-life figure that he's entitled to portray whoever he wants however he likes. But this argument doesn't hold up very well because 'Casanova' isn't just a name, it became an adjective defining a womanizer, so when the director who expressed to the fullest his lust for women and life's pleasures, makes a film about Casanova, maybe it's because there's something of Casanova in il Maestro, if he doesn't mind.Indeed, for all his nobility, Casanova is a sex-addict, with a constant craving for the weirdest and most grotesquely unusual performances. Donald Sutherland, with his high stature, his shaven forehead, his false nose and chin and fancy clothes looks like a giant turkey, but within this weird appearance, he stands above his peers, as if his aura elevated him despite himself. He's a complex and paradoxical figure. There's a sort of running-gag where he keeps praising his intellectual and scientific merits, and he was a versatile fellow indeed, but no one ever cares for this aspect. His reputation always precedes him. Am I going too far by thinking that Fellini would share a similar frustration, being constantly associated with his baroque universe made of parties and voluptuousness? A way to show that even the brightest minds embraced sex, as a form of expression? Now, how about women? The film is as full of sexuality as you would expect from a "Casanova" biopic, but there is something deliberately mechanical and playful in the treatment (one of the most passionate encounters is with a doll actually) as if Casanova's sexual appetites were more driven by a disinterested quest for prowess and games than one of the ideal woman. The visit of the belly of the whale could be seen as Freudian symbolism, but I don't think Casanova had such oedipal impulses as he's not even tempted to join the tourists. We all have one mother, but we can have as many women as we want; they can have motherly roles, but that doesn't seem like what Casanova is looking forward to discovering, diversity is the key.And as to illustrate this diversity, the film is built on the picaresque episodic structure where Casanova makes many encounters with every kind of women: young, sensual, depraved, weak, fainting, chanting, pretty, freakish, ugly, the film is very repulsive but appealing in an appalling way. And maybe the greatest trick Fellini ever pulled was to confront men with the hypocrisy of monogamy, as Casanova, the Fellinian, is proved right through one simple thing: pornography. The lust for sex has reached such maturity that men aren't aroused by pretty faces and perfect bodies anymore, the uglier, the older, the dirtier sometimes, the better. Fellini and Casanove reconcile men with their polygamist nature.And this is why I recommend not only the film, but the DVD Bonus Features. In a little documentary made before the shooting, many Italian actors were interviewed about Casanova. Ugo Tognazzi said that in the pre-Revolution period, some dishes were left deliberately rotten in order to have an extra taste or smell, appealing to gourmet tastes. A classic beauty is revered and praised, but that's not what men are looking for. The documentary is followed by a visit to a nightclub and many 'Casanovas' explain their tricks: feigning indifference, being genuinely shy, showing that they care for women, they might not all act like Casanova but they have one thing in common, they know how to create desire, and more than anything, to satisfy it. You just don't earn a womanizing reputation by being impotent. The secret is to be aroused and excited by everything, it's a discipline.The score of Nino Rota has something mechanical about it, or experimental, but it fits the tone because Casanova took sex seriously, like an accomplished athlete looking for self-improvement, so a sensual music couldn't have worked. But I less enjoyed the sex, a bit outdated even if the treatment was deliberate, than the enigma of Casanova, a man who was ahead of his time because he understood, before everyone, one of the main drivers of society, sex and desire, and he expressed it to the fullest, and we somewhat envy him, although the word 'Casanova' has something pejorative about it, but in Italy, the perception is different, it's a part of the Italian psyche, and like Mastroianni said in the documentary, a psyche symbolized in the film's opening with a giant Venus' statue emerging its head in Venice before plunging again, as if it was all a dream.The Venus metaphor seems to indicate some guilt behind the 'Casanova' heritage, there's a little of Casanova in every Italian man, in every men, but maybe that's nothing to be proud of. Anyway, like Macchiavelli, the man became an adjective, something our mind can relate to with more or less shame, it's only fitting that the director who made a movie about him, also inspired an adjective. Indeed, there was something Fellinian about Casanova... so the title sounds a bit like a pleonasm.

Churlie_Chitlin

If you have ever found yourself watching a movie like Emmanuelle and thinking: "This would be great if it were an 18th century costume drama with less nudity and enough nightmarish surrealism to make even David Lynch weep for mercy," then this is the movie for you.Donald Sutherland plays the infamous Count Fucula, a man who tries to have sex with everything he sees that resembles a female, and whose sexual technique generally consists of laying on top of a woman and bouncing up and down on her like he's humping a trampoline - and all without ever even taking off his pants!Short girls, tall girls, blonde girls, brunettes, girls with hunchbacks, female robots.. you name it, he tries to screw it. At one point, I thought he was going to try to make it with a giant turtle. A missed opportunity, if you ask me.Until now, I thought Satyricon was the weirdest Fellini ever got, but this one makes it look square in comparison.

zolaaar

It's certainly important to note that Fellini thought that the historical Casanova was a scumbag, a crook even a fascist. In his film, the character appears as a scatterbrained, melancholic, mechanical tragic figure: like a marionette, a Pinocchio who never turned into a human. The story starts in Venice, Casanova's home town, with a Fellinesque carnival scene, where a statue of Venus is pulled out of the canal. This effigy with its protuberant, blue eyes is an equally powerful initial motif like the Christ figure in La dolce vita. And there we have the comparison: both films show similar dreary worlds of vices. Like Marcello, Casanova strays from one orgy to the next, screws around randomly. Donald Sutherland is remarkable, and it is intriguing to look at his unimpressed, incurious, lost soul wandering between the splendid masks and suits of the high society which makes Casanova basically another picaresque tale and like La dolce vita and Satyricon totally excessive in every aspect. And this shows Fellini's strength and weakness. The principal fault is probably the main protagonist himself. Casanova was not only a woman 'eater', but also a literarily educated man, mathematician and politician with knowledge in economy, science and occultism. Just like the French ambassador who watches the screen Casanova copulating, but leaves before he is about to say something, Fellini refuses the opportunity for the historical character to defend itself. The direction on the other hand is, as usual, masterful. What remains is a clinical, highly reserved character study, spectacular, but cheerless.

Graham Greene

It is a common misconception that Fellini became worthless after his grand-masterpiece 8 ½, with most critics dismissing all but Amarcord as lightweight, over-blown odes to pretension, not fit to hold a candle to the low-key delights of La Strada, Nights of Cabiria, etc. Though it's true to say that Fellini's interest in "straight" cinema post-8 ½ did wane slightly, with films like Juliet of the Spirits, Roma, Satyricon and The City of Women all substituting character depth and clear storytelling for grand gestures and theatrical stylisation, there were at least a few of his later films that have aged surprisingly well and can, in some respects, be viewed in hindsight as being as interesting and artistically relevant as those earlier, more acclaimed works.Casanova is one such film, as far as I'm concerned. Certainly, the film can be seen as excessive in the most self-indulgent way possible, what with the stylised set-design, reliance on theatricality, over-the-top performances, and all manner of outrageously comedic, wildly frivolous, fornication. Fellini carefully mixes the highbrow (discussions of art, philosophy and the notions of freewill) with the lowbrow (clowns, carnivals, sex contests and the kind of innuendos usually reserved for Benny Hill), structuring his film in a highly episodic fashion so that it (at times) feels more like a collection of scenes as opposed to one long cohesive films (though, having said that, pretty much all of Fellini's later films were defined by their episodic structures). It certainly won't be a film that every one will appreciate. The middle-part of the film (in which Casanova falls in with the carnival set and the seductive giantess) drags a little, whilst younger audiences might find some of the more earnest scenes laughable (the ending is particularly touching).Like all of Fellini's films from La Dolce Vita on, the cinematic design is absolutely impeccable, with the director creating his usual (or should that be unusual?) fantasia of abstract architecture, theatrical lighting and seas made of shimmering sheets of plastics, in which he drops characters chosen more for their physical look and presence, rather than their acting ability. This adds to the overall dreamlike (or nightmarish) atmosphere that the film seems to play on, with the only real anchor to the story found in the humanistic performance of Donald Sutherland as the titular anti-hero. Now, before anyone starts to question the casting of Sutherland - instead visualising a Heath Ledger type of blonde locks and rippling muscles - it is important to note Fellini's obsessions with the grotesque; in both the physical and the mental. His image of Casanova is of a lanky, gaunt, balding buffoon, who peers down his jagged roman nose at the intellectual cretins who are supposedly his equals. He's strangely reminiscent of Mr. Burns from the Simpsons, what with the whole look and attitude, but... instead of letting him becoming yet another Fellini-esquire caricature, Sutherland allows shades of depth and humanity to permeate the arrogant and pompous exterior.So, on the one hand, we have Casanova as a pompous, strutting, impotent grotesque, but on the other hand, we also have a man capable of intellectual discussion, poetic thought and moments of intense loneliness. After two hours of epic spectacle, painterly visuals and more slapstick sex than you can shake a 'Confessions Of...' at, we begin to see what Fellini intended with his depiction of Casanova, with the underlining concept of unrequited love and the notion of sex and death, sex as loneliness (etc) and the ultimate downfall of a man who'd built his entire reputation on lust and virility slowly brought down by the ravages of old age and the scorn of a younger generation. The most touching scene in the film for me - and the entire reason as to why I view Casanova as a minor-masterpiece - comes towards the final act of the film, when the aging Casanova breaks off from a rowdy dinner engagement and finds himself alone with a mechanical ballerina. Consumed by a deep desire for the marionette, which reminds him of a lost love from the past, Casanova watches the doll dance and twirl and states that something so beautiful should be spared the indignity of seduction... however, he later sleeps with the doll, ultimately beginning the downward spiral that will bring us to the end of the film.The final scenes of Casanova are very vague, and I'm certainly not going to pretend that understood everything that Fellini was trying to say. Ultimately, the film worked for me because I understood what the director was trying to say in regards to unrequited love and I felt that Sutherland's performance (certainly one of the most neglected performances he gave in the 70's) managed to undercut the more over-bearing elements of Fellini's direction, and gave us a real character filled with pain, fear and emotional contradiction. The pace and structure of the film and the idea of a central character as a writer telling the story as it unfolds is reminiscent of La Dolce Vita, something that other viewers and critics have pointed out elsewhere, with the idea that the two films are merely different variations on the same story.The film is flawed, without question, but at the same time I find it absolutely fascinating and beautifully put together. It's appeal will no doubt be limited by the theatricality of the design and the stark, caricatured performances, though I feel the film will, regardless, appeal to those viewers who appreciated the director's other key-works from the same era, particularly that nightmarish cornucopia of excess, Satyricon, the free-form reminisces of the picaresque Amarcord, and the grand-allegory of ...And the Ship Sails On. It's also worth a look for Sutherland's central performance as the libidinous wretch, and for anyone who appreciates difficult, highly-visual, European cinema.