IslandGuru

Who payed the critics

Ameriatch

One of the best films i have seen

Platicsco

Good story, Not enough for a whole film

Kayden

This is a dark and sometimes deeply uncomfortable drama

GeoPierpont

Oh dear heaven, this woman can act and I never knew it even though I watched "Ninotchka"... I swear I had no idea she could convey so many emotional pauses through life like she did with this film, kudos my dear!!Of course much credit is due to Dumas but my friends this is one of a kind entertainment venue you will never find again. She is perfect in any scene and I am one to discern any and I mean ANY discrepancies in virtue, sincerity, and most importantly convincing emotional transference. What a woman!!High high high recommend for romantics, Garbo fans, she is absolutely stunning and wish I could see more of her in these roles. Amen.

secondtake

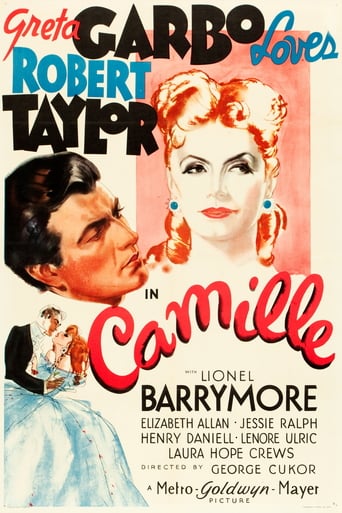

Camille (1936)This melodramatic tale of true life in the face of the strictures of social reality is tried and true. You feel for both the male lead (Robert Taylor, who is quite good) and the female (Grate Garbo, of course, who is excellent). That's the whole point. These are two people who are not quite appropriate because they come from different social levels, but there is a sense they could make it work if they wanted to.But outside forces get in the way. Chief among them is the man's father, who wants to save his son from a marriage that will ruin both husband and wife. This is a key role in the film, and a critical if brief 10 minutes or so. The father is played, importantly, by Lionel Barrymore, who does little else int he movie. But here he makes his case to the Garbo with amazing force. It's a great scene, even if you wish Garbo would leap up and say, no, no, I'm going to follow my heart.But exactly what happens is what the movie is about. The rules of the culture of the time (1800s France) prevent an honest sense of two people marrying out of simple love for one another. In a way, that's the whole point of continuing the old Dumas story, which has resonated for decades into the Hollywood era. I'm not sure it would work now, except as an historical drama. This is set in the period (around 1850) and feels legit. Unlike the curious (and not bad) 1921 silent version, which sets it in a 1920s culture, this one transports us back to the original. Fair enough! There is a contrived quality to the plot, for sure, partly because of its origins. While this doesn't ruin the whole enterprise, there is a slight feeling of being led along the whole time. Garbo and Taylor are both terrific, however, and we feel some honesty to their feelings for one another. It's on that basis that the movie works. And it really does, even through the over the top drama in the last scene. Moving and beautiful overall.

Robert J. Maxwell

What can you say about a thirty-one year-old woman who died? That she was carefree, gay, romantique? That she danced divinely? And why not -- she was played by the divine Greta Garbo? That she was invented (or refashioned) by the son of the guy who wrote "The Three Musketeers"?That she captured the attention of the meta-handsome Robert Taylor? That Robert Taylor's real name was Spangler Arlington Brugh? That she suffered from one of those diseases that are periodically romanticized? That in the 1960s it might have been schizophrenia but in 1847 Europe it was tuberculosis? That tuberculosis, like pregnancy, was supposed to transfigure a woman's beauty? That it was believed to make her thin, pale, waif-like, alluringly enervated? That Dumas fils book was so successful he dramatized it and Verdi turned it into an opera? That in Charles Jackson's 1944 novel "The Lost Weekend," the protagonist watches this movie and is moved to tears by it? That the author of that novel was bisexual? That the director of this movie was gay? That Truman Capote sneaked into Garbo's New York apartment and reported to The New Yorker that one of her abstract paintings was hanging upside down in the vestibule? That Truman Capote was gay? That Garbo's most devoted fans probably contain a disproportionate number of gay guys? That that last generalization strikes even me, its own author, as a little Olympian? That Greta Garbo always struck me as a little beefy? That here she does a good job of acting casually reckless? That these tragic love stories in which someone -- usually the woman -- dies a death that we don't see as disfiguring are getting a little tiresome? That I'm still struggling to recover from Erich Segal's "Love Story" of 1970? That the first sentence of "Love Story" is, "What can you say about a 25-year-old girl who died?" That Robert Taylor had about ten years during which he tried to act from a position other than "default," which was snarling, masculine, a little coarse? That in "Westward the Women" he even gets to use a bull whip on a dozen ladies who are pulling his Conestoga for him? The answer to these questions is obvious and clear. I don't know.

Steffi_P

The great literary romances of the late nineteenth century, despite perhaps being presumed today to be models of propriety and principle, were more often than not frank tales of adulteresses and prostitutes. When many of these great works were adapted for the screen in the 1930s, the most natural choice for a leading lady was often Greta Garbo, than whom there was none finer at portraying such fallen women as noble and tragic heroines.Garbo was one of the cinema's great natural performers, and in her day was probably the most genuine person to have graced the screen. She brought something to these roles not only because she was dangerously beautiful, but also because she was irresistibly human. Even when her character lied to her lover she could make us sympathise with her motives, as well as understand why the lead man was so enamoured of her to be taken in. In Camille, she brilliantly captures the conflict between Marguerite's strength of character and her physical frailty. Her occasional coughs and lapses into weariness are so neatly understated, but in a way that makes us accept that she is fighting against them rather than that they are insignificant.Whether Garbo's professionalism rubbed off on others, or whether it was the intensely personal direction of George Cukor, Camille also features some superb performances from what could have been a disappointing supporting cast. Lead man Robert Taylor (who once described acting as the easiest job in the world) was generally little more than a handsome but wooden matinée idol, and yet here the youngster pulls off his part like a pro. True, for the first hour of the picture he is simply a handsome, grinning mug, but when his character is required to display some emotional depth he steps up to the task. Henry Daniell and Lionel Barrymore were both shameless hams, but here they are at their most restrained, without losing any of their trademark qualities. When you compare Daniell in Camille to his other performances, it's like seeing the real person that a caricature is based on.While the sincerity of the cast certainly helps to give Camille its emotional intensity, it is the direction of Cukor which gives it its pace and watchability. Cukor's cinema is all about movement, and he has a hundred tricks up his sleeve, each using motion to draw our attention or set tone. Take Garbo's big scene with Barrymore. The two of them are essentially just wheeling around a small room, but Cukor keeps his camera up fairly close, emphasising their almost constant changes in position. This gives an unsettling, desperate quality to the scene, even giving the impression that Barrymore is chasing Garbo. At other times such rapid change would be distracting, especially if the scene contains a lot of important information, but Cukor still uses subtle shifts in perception to keep the narrative feeling fresh and meaningful. For example in the lengthy episode at the opera where we meet the principle characters for the first time, Cukor uses the fuzzy glow of the stage as a backdrop for the first meeting between Garbo and Taylor, and the blandness of the box for the equivalent encounter with Daniell.Both the acting and the direction here are purely cinematic, the former glamorous yet honest, the latter unobtrusively guiding the audience with the moving image. And yet it takes away none of the integrity of Alexander Dumas fils' novel. And so this final nod is to the hidden hand behind the screen - producer Irving Thalberg. Thalberg's aim was never simply to make a fast buck; he wanted to leave high quality product behind him. It seems that pictures like Camille are what he always aspired to - ones that harnessed all the faculties of the medium, yet were as prestigious and culturally significant as any classic play or novel. This was among his last productions, and he died before it was released, but it is undoubtedly a worthy asset to his legacy.