tieman64

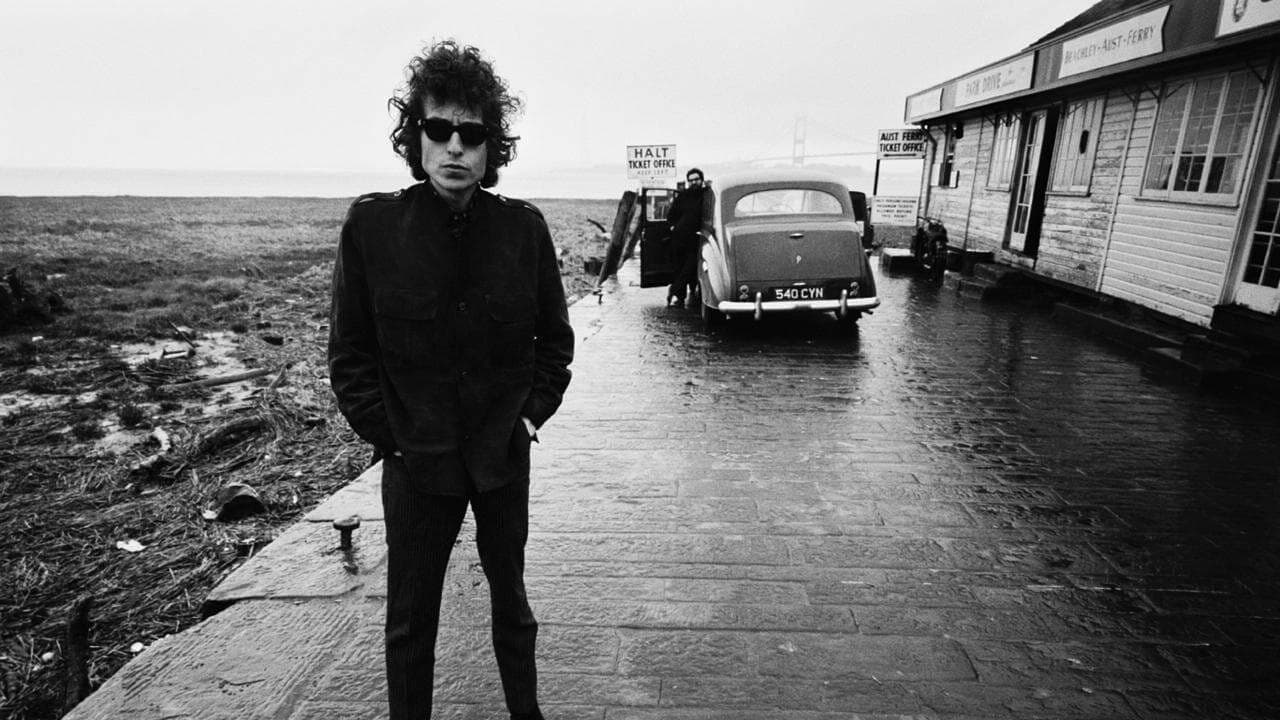

In the 1920s, right through to the 1950s, the FBI began suppressing both the history of politically engaged early 20th century writing, and radical artists themselves. Only art which managed to evade repression tended to squeeze through. Historian Claire Cullen says that this resulted in a "version of modernism that was apolitical and stylistically abstruse". During this period, countless famous artists (Hemingway, Brecht, Richard Wright, Joyce, Jean Renoir, John Galbraith, Norman Mailer, Ginsberg, Faulkner, Steinbeck, Sandburg, Dreiser, Pearl Buck, Dorothy Parker, Thomas Wolfe, Georgia O'Keeffe, Tennessee Williams etc) were also monitored, as well as radical singers like Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie.In the 1960s, the FBI's Counterintelligence Program began focusing on musicians and artists whom they dubbed, quote, "domestic enemies", "advocates of new lifestyles" and "apostles of non-violence and racial harmony". These supposedly dangerous artists (the Rolling Stones, Hendrix, Elvis, Charlie Chaplin, John Lennon, Bob Marley etc) were, in the eyes of the state, "subversive", "anti-American", "members of the New Left", "pacifists", "communists", "dangerous intellectuals" and "progenitors of cultural revolution". Other declassified papers would refer to them as "highly political and unfavourable to the administration". Between 1968 and 77, most had died.One who survived, and one of the last active connections to that era, is singer/song-writer Bob Dylan, the subject of "No Direction Home", a documentary by Martin Scorsese. Scorsese's film is divided into two parts. In the first, we move from the mid 1950s to 1963. Here we watch as Dylan grows up in a Minnesotan mining town and begins to get hooked on music. Dylan's many influences (Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, Tommy Makem, Huddie Ledbetter, Chuck Berry, Little Richard etc) are touched upon, but only superficially. This is understandable. Part high modernist and part postmodernist, Dylan's influences are almost too boundless to map, his songs (he's written over five hundred) drawing extensively from poetry, literature, religion, cinema, history, early blues, rock, folk, country, gospel and jazz.The film's second half focuses on a roughly six year period, starting in 1960. Here we watch as Dylan becomes a popular political/folk singer and becomes swept up in various civil rights movements. During this period, some of Dylan's best political material was written, most notably "Masters of War", "When The Ships Come In", "Blowing in the Wind", "Chimes of Freedom", "The Times They are Changing", "Hard Rain's Gonna Fall", "With God on Your Side", "Maggie's Farm" and "Talking WW3 Blues". Meanwhile, songs like "Oxford Town", "Only a Pawn in Their Game", "Death of Emmett Till" and "The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll" focused on the plights of African Americans, whilst others ("Motorpsycho Nightmare", "John Birch Paranoid Blues") poked fun at anti-communist hysteria. Funny, apocalyptic, ambitious and angry, all these songs were perceived as new sounds. Dylan himself, though, began to distance himself from politics. Though he went to the southern states with Pete Seeger in support of black voter rights, and sang next to Martin Luther King during the March on Washington, he only rarely got involved in public political action.Scorsese, though, doesn't care about politics at all. He ignores Dyan's political roots, ignores Dylan's life in the bohemian Greenwich Village and ignores Dylan's relationship with 19 year old Suze Rotolo, a communist and daughter to prominent communist/activist parents. During this period, Dylan filtered many of his songs through Suze. Scorsese's film then watches as Dylan rejects his fan-base and moves from political-folk to electric, rock and country ballads. Why Dylan rejects them is made clear: they're looking for a leader, a voice, a messiah, an Answer. But Dylan refuses to comply. His 1964 masterpiece, "My Back Pages", would mark the point at which he openly breaks ties with civil rights movements. Scorsese, though, offers Dylan's May 1965 Newport Folk Festival appearance, where he "went electric", as the precise moment in which Dylan turned Judas. Betrayer. Regardless, to folk fans and even artists like Seeger, Dylan's switch to electric was an admittance that he now refused to pen protest songs. To them, Dylan was now a reactionary. A sell out (though he'd occasionally still release protest songs, from the 1970s onwards Dylan primarily offered a mix of esoteric folk, country and blues). Ironically, even Guthrie was accused of similar things, co-opted by the Roosevelt government to promote the New Deal, and paid by the state to sing in towns and villages which were about to be destroyed to make way for hydro-electric schemes.Elsewhere Scorsese attempts to chronicle Dylan's impact on 20th century American popular music - Dylan politicised pop and brought both folk and complex/ambiguous lyrics and song structures into the mainstream - but the results are again superficial. Scorsese's suggestion that Dylan needed to move away from topical songwriting to be able to reach the heights of "Bringing It All Back Home" and "Highway 61 Revisted" is likewise dubious, and the director seems uninterested in examining the relationship of art and artists to questions of social liberation."No Direction Home" is at its best when it offers us glimpses of concert footage. Later Scorsese clumsily attempts to convey a simple theme. In Scorsese's hands, Dylan is just a guy who "refuses to be pinned down". Like the chorus of his 1965 classic, "Like a Rolling Stone", Scorsese's Dylan is a constantly shifting stone without direction (also the thesis of Todd Haynes' "Im Not There"). None of these statements are true. Dylan may be nasally, his words may be vague, he may have constantly changing, weird inflections, and no two live performances of his songs are ever the same, but the idea that he has been a cryptic chameleon has never been true. If anything, Dylan's a one man archive of a very specific type of American mythology. He represents a kind of shared nostalgia, an interactive museum whose malleable lyrics allow listeners to tap into a vanishing America.7.5/10 – See "Don't Look Back" (1967) and "Bound for Glory" (1976).