GamerTab

That was an excellent one.

CrawlerChunky

In truth, there is barely enough story here to make a film.

Cheryl

A clunky actioner with a handful of cool moments.

Allissa

.Like the great film, it's made with a great deal of visible affection both in front of and behind the camera.

overdarklord

The movie is a great example of japanese war dramas and definitly worth watching.However, I think this movie could have been a bit better and I will use this movie to talk about 2 things it and many other movies do wrong in my opinion.

For one, the movie uses extensive crying scenes to convey to the audience that the characters are sad and that we should feel bad about them. The funny thing is that the movie has great drama. I mean its war time, people are being cencored, people are dying and everything has this very depressing tone already. Seeing your characters burst out in tears during normal conversations is in my opinion cheesy and nothing else.

It is basically the idea between showing the audience sadness directly and implying it and only making the audience feel sadness through the tone. The latter one being hard to achieve but when it hits, it hits hard. The first one feeling more easy and forced in my opinion and therefore can not convey the same emotion. Of course there are some great drama scenes with people screaming and crying heavily but everything has its place and time to make it believable and subtle.This movie has this great moment, when after the war the teacher was on a boat with her son and told him one of her former students wanted to row the boat for her as well and then she mentioned that he died. It was a great moment because it implies that not only that one boy but many of her students died during the war and since the audience knows them cares about their deaths, even if we dont know every of her student by name, the lose of the war is implied... but then a few minutes after that they show her infront of the graves of EVERY single lost student of hers, crying while showing their name. One of those 2 drama scenes is done right and the other is forced and cheesy.The second idea i want to talk about is when to end your movies. Its a compromise between delivering a finished package, framed with perfect edges, or having it a bit raw and unformed open for the imagination or even interpretation. You know making an ending that is open but not too open is very hard, but so is having it complete but not too drawn out. I myself like it more when things are unfinished and I have the longing for more, because I know if I had gotten more I would have wished it had been shorter.

Often times films dont know when to stop and miss the perfect opportunity, which I find very frustrating.

In "twenty-four eyes" you have this perfect scene at the end where the teacher is in her classroom again, seeing faces that look very similair to the children she tought 18 years ago (for one because they were to same actors, but storywise they were the children of her former students)

This was right after the drama scenes that hammered in the loss this war created. Now we have this scene that conveys this message of hope and familiarity. The idea that there is a future and not everything is lost. Basically the perfect way to end. ....Execpt it went on for like 15 minutes with a reuniting scenes with all the former students and the teacher. It felt to me like the movie really wanted to hammer home the anti-war message more and show the audience how much the characters lost, even though we know that already. As if I was a child who has to be told that for like half an hour in order to understand it. You know this anti-war message is nice and all but dragging on your movie because of it and ruining the perfect ending for it really doesnt seem like a good idea.It must seem like I hated the movie, but I really dont. I dont give 7 stars out to every movie I see, you can see that by my scoring system. But i get really frustated when a very, very good movie get torn down by such small things.

lasttimeisaw

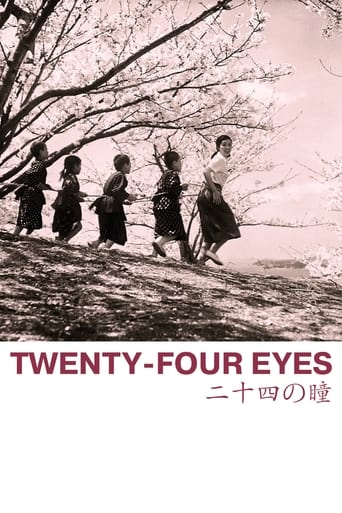

A lyrical reflection on WWII, Japanese director Keisuke Kinoshita's magnum opus TWENTY-FOUR EYES is prominently, steeped in his humanistic take on the solemn state of affairs, entrusts a good- natured school teacher Hisako Oishi (Takamine) as the cynosure, and the title is a metonymy for the 12 first-grade pupils who grow up under her auspices through the turbulent years from 1928 to 1946 in a bucolic Shodo Island. In 1928, Hisako is the new teacher of the village school and in charge of 12 first-graders (7 girls and 5 boys), she wears a suit (instead of a kimono) and commutes by a bicycle, regarded as too modern in others' provincial eyes, but in fact it is nothing but being pragmatic. Radiating a cordial devotion to each of her pupils (a roll call sequence points up their strong bond which would sustain through the shifting sands of kismet), the young Hisako consolidates the mutual affections through folk songs and Kinoshita hammers home to viewers that those kids' innocent visages can soften any impervious hearts, which will become his stock-in-trade in the subsequent jeremiad.Incapacitated by a jejune prank, Hisako's condition means she cannot ride a bicycle when one of her tendons is broken, so she accepts to be transferred to a nearby school for older students and promises that they will reunite in 6th grade, the touching farewell scene hits the mark of poignancy after a preceding snippet where the 12 tots play truant to visit Hisako in her home on foot. Then the time-line swiftly jumps to 5 years later, in 1933, a remarkable feat should be credited to the casting director, who has gathered the group of 12 six-graders possessing a stunning resemblance of their younger archetypes. Hisako gets married, while the teacher-student dyad becomes ever closer, extrinsic forces begin to assail the individuals: one girl must take on the duty of rearing up her new-born baby sister after her mother passed away, and a double whammy befalls when the said baby also dies, instead of returning her to the school, her father decides to send her away to work as a waitress in a restaurant; similarly another girl unwillingly withdraws from the class when it is her turn to assume the role as the family cook; for boys, that is another story, indoctrinated by the ultra-nationalism all the rage, they are hot to trot to volunteer as soldiers to Hisako's utter dismay, who resolutely values human lives more than any ideological fanaticism, after the school principal reprimands her for her "coward" and dangerous thoughts, a disillusioned Hisako also parts company with her lofty vocation. A fast forward to 1941, pupils grows up into adults, to whom Hisako stills holds very dear, and herself is a mother of three. The ongoing WWII conscripts all the militia, a harrowing tête-à-tête with a tuberculosis-inflicted former student tellingly conveys a pandemic hardship and dread hovering above each household. Personal tragedies will strike Hisako one after another, but those who survives must go on with their lives. Another five years go by, in 1946, after the damning war fizzles out, Hisako resumes her job and tearfully finds out among her new pupils there are offspring of her endearing first first-graders. A celebration organized by the remaining 14-eyes, including a pair of blind ones, brings them altogether, there will be tears, fond reminiscences, but also signifies a brighter future ahead, no doubt Kinoshita is a maestro of emotional manipulation but he has notch it up without betraying any trace of affectation, and the film's ultimate confluence really packs a punch to our tear gland. Also, sterling children performances are cogently elicited through Kinoshita's orchestration, sometimes to a fault of immoderation (with a combo of watery eyes and plaintive dirges), but as a whole, it is a pretty amazing achievement; in the central stage, Hideko Takamine superbly sinks her teeth into a character laden with a gaping age range, and her personable charm and sincere timber thrust an irresistible impact to our likings. Typically shot at a remove with a ritualistic respect to its characters and milieu, and forfeits any idea of employing front-line bombardments to mess with our sensorium, TWENTY-FOUR EYES is a potent tearjerker illumining with a sagacious anti-war message, but also an ode to the unflagging strength inside an ordinary woman, the very rudimentary but foremost essence that makes us a decent human being.

thomaskasaki

25 years ago I made up my mind I would move to Japan. So I wrote to people in Japan who had lived there for over thirty years, and asked them what would be the #1 movie I should watch that encapsulated the spirit of the Japanese.They all suggested "24 Eyes". Now, after having lived in a strictly Japanese environment for five years, and having seen well over thirty Japanese movies, not to mention over a thousand hours of TV shows and animae, it is still the #1 to me. By today's standards it will seem extremely "G" rated, a little too slow and a bit too long. But for those who want to really understand people, and where they are coming from, I can't think of a better movie to recommend. I wish every culture, particularly those that may be going extinct, would use this movie as a guideline to tell their story.

Howard Schumann

Considered by some Japanese critics as one of the ten best Japanese films of all time, Keisuke Kinoshita's Twenty-Four Eyes is a moving tribute to a teacher's dedication to her students and to her progressive ideals. The film spans twenty years of turbulent Japanese history beginning in 1928 and continuing through the end of World War II. Though to Western eyes it can be at times oppressively melodramatic with its overuse of such sentimental melodies like "Annie Laurie", "Auld Lang Syne", and "Bless This House", the film was extremely popular in Japan, beating out such highly regarded classics as Mizoguchi's Sansho Dayu, Kurosawa's Seven Samurai, and Naruse's Late Chrysanthemums for Best Film in Japan and Best Foreign Film at the Golden Globes.Adapted from a novel by Sakae Tsuboi and set in the rural island of Shodoshima, the title refers to the eyes of seven girls and five boys, the twelve students of first grade teacher Hisako Oishi (Hideko Takamine), endearingly called "Miss Pebble". As the film opens, a confident new teacher, Miss Oishi, rides to the school on her bicycle dressed in modern Western clothes but soon has problems being accepted by the working class villagers who think that she is a wealthy outsider. The senior teacher (Chishu Ryu) at the primary school even asks why the authorities would send such a good teacher. Miss Oishi is also criticized for calling the students by their nicknames, inquiring into each child's family life, and singing folk songs instead of the school anthems.Later, during the Japanese invasion of China, she is suspected of being a "red" because she discourages her young pupils from becoming soldiers but does not protest when the headmaster burns one of her books. Proud but traditionally passive, she refuses to intervene in a family dispute when one of her students, a gifted singer, expresses a desire to attend the conservatory rather than go to work in a café, and does not attempt to raise funds to send one of the poorest students on a school trip. Miss Oishi is able to gain a share of acceptance, however, after an injury to her leg sidelines her for several months and the children visit her without being aware of the length of the journey. It is only when she meets the crying children on their way to her home that reconciliation with the community begins to take place.Unfortunately, the length of the trip to the school forces Miss Oishi to transfer to the middle school closer to her home and she will not teach the same children for five years. Miss Oishi is a compassionate teacher who does not want to see her bright young students killed in the war but the growing conflict in China and the increasing poverty in the village force the young men to become cannon fodder for the militarists with unfortunate results. Twenty-Four Eyes to our modern view has many excesses including its almost three-hour length but the purity and radiance of Takamine as the compassionate school teacher shines through and the film allowed Japanese audiences to experience a cathartic expression of the sadness and loss caused by the war.