ChanFamous

I wanted to like it more than I actually did... But much of the humor totally escaped me and I walked out only mildly impressed.

Myron Clemons

A film of deceptively outspoken contemporary relevance, this is cinema at its most alert, alarming and alive.

Ella-May O'Brien

Each character in this movie — down to the smallest one — is an individual rather than a type, prone to spontaneous changes of mood and sometimes amusing outbursts of pettiness or ill humor.

Yazmin

Close shines in drama with strong language, adult themes.

TheLittleSongbird

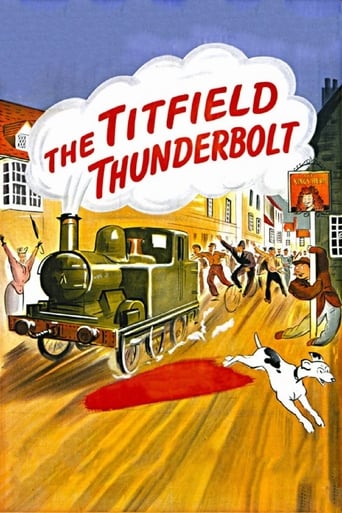

The Titfield Thunderbolt is not Ealing Studios' best work, nor does it try to be. It is essentially a charming and entertaining film that does let off a warm glow. Yes, even if the tone is patronising occasionally and some of the characterisations a tad sketchy, the story while on the slight side is always entertaining with enough charm to suffice. The cinematography, scenery, costumes and especially the trains are a delight to look at as well, and Georges Auric's score is jaunty and memorable. The satire in general entertains, the script has its quotable parts, the film is very well directed and the film moves along briskly. The performances are also polished with Stanley Holloway especially shining in the lead. Overall, even if the studio were starting to run out of steam, The Titfield Thunderbolt still makes for pleasurable viewing. 8/10 Bethany Cox

Terrell-4

Of the great British comedies that came out in the late Forties and early Fifties, one of my favorites is The Titfield Thunderbolt. There's no hero, no heroine, no romantic shenanigans and not even dominant players. After two generations of dumbing-down humor where the height of hilarity now usually centers on bedtime performance anxiety and flatulence, The Titfield Thunderbolt seems ever more clever, funny, and above all else, charming. Passion there is aplenty...all directed at old steam engines. When British Rail announces that it's shutting down the Titfield-Mallington branch rail line, the Titfield villagers aren't having it. They organize, (politely, of course) to make the case that they can run the line even if British Rail won't. They get their chance, but have only a month to prove they can turn a profit and be on time. Waiting in the wings are two scheming bus line operators who are planning to make sure the villagers fail. The problems are daunting. They have the engine and the passenger cars, but they must raise ten thousand quid. Vicar Sam Weech, who loves God, his parishioners and steam engines, not necessarily in that order, suggests a raffle, a bake sale and a charity performance of The Mikado. By now we've met many of the villagers, and we love them all. There's the Vicar (George Relph), aging and determined; the young squire, Gordon Chesterford (John Gregson); the wealthy and happy quaffer of spirits, wine and ale, Walter Valentine (Stanley Holloway); the drunk old former railroad man, Dan Taylor (Hugh Griffith), who lives in a crumbling, ancient passenger car; Harry Hawkins (Sid James), who operates a road roller and likes few people; and on we go. It looks like the villagers might prevail...but the bus company strikes back. The duel on the tracks between the steamroller operated by the tough Hawkins and the steam engine with the elderly vicar at the throttle is, as Jack Black fans so often say, awesome. Even so, with their engine sent down a gully it looks finally that disaster has struck...and then the villagers remember the Titfield Thunderbolt. This old steam engine is so out of date it's been in the Titfield museum for years. It must be watered, fueled and run across country to the tracks if there is a hope of success. Well, there'll be more than a hope. Charles Crichton keeps this movie moving with such briskness we might forget how skillful he is. Within five minutes he's given us the set-up. Within ten minutes he's introduced most of the characters. He places time-delay second takes in the movie so that we find one situation amusing and charming, then 20 minutes later it comes into play again in a different way that makes us smile even more broadly. If you want to see skillful comedy planning, keep an eye on Dan Taylor's hovel of a home. Crichton let's us know these people much more by what they do than by what they say. The Titfield Thunderbolt is so good, so charming and so gentle because we see just how indomitable these people are going to be. They are faced with problem after problem. With ingenuity, perseverance, good cheer and astonishing improvisation, they overcome. When Crichton sends the people of Titfield and other nearby villages running across fields and dales to give the Thunderbolt a push up hill, it's grand. It takes a village to raise a steam engine. (And while the village of Titfield is fictitious, the movie was shot near the village of Limpley Stoke, an equally fine name, which is not.) Crichton was a maker of gems. You'll be rewarded if you track down and watch Hue and Cry (1947), The Lavender Hill Mob (1951), and The Battle of the Sexes (1959). Against the Wind (1948) is a fine behind-the-lines adventure set in WWII. He fell out of fashion and spent years in television. John Cleese rescued him for a last, victorious hurrah when he was 78 to co- write and direct A Fish Called Wanda.

JoeytheBrit

One of the lesser Ealing Studios comedies of the 50s that are fondly looked upon today as the quaint legacy of a bygone age, The Titfield Thunderbolt shares many of the characteristics of its more celebrated peers (Passport to Pimlico, etc) – especially in its story of everyday folk rallying against a dictatorial bureaucracy (in this case, British Rail, who close down the village's railway line) – without quite attaining their sublime heights. The reason is probably down to T.E.B. Clarke's script, which, relying as it does on comedy stereotypes that date all the way back to silent days, is disappointingly sketchy. We have the saintly vicar, the rascally poacher, the booze-loving lord, etc none of whom have any real back story to speak of. John Gregson is the notional male lead, but has very little to do, and is given no love interest, and so can't help but come across as bland.And yet, despite all this, the film has charms that make spending an hour in its company not unpleasant. It has that aura of a gentler time now lost to us – and which, in all likelihood, never really existed – and seeing the familiar faces of Gregson, Sid James, Hugh Griffiths, Stanley Holloway and Naunton Wayne is always a pleasure. Funniest moments for me have to be the drunken joyride in a stolen train enjoyed by Holloway and Griffith through the streets of the sleeping village, and the site of dear old Edie Martin trying to get a train's furnace going by covering its hatch with a tea towel.

pjm-16

The working class stereotypes, written in by middle class script writers, are lazy, dishonest and untrustworthy( ala Hue Griffiths) or simply stupid (Syd James). The vicar and other village bigwigs have much more admirable qualities as have the other middle-class characters.It all takes place in a kind of idealized world that never really existed, yet still manages to make many present day people feel nostalgic for a past that never was.This kind of class racism is alive an well on BBC Radio 4, if you care to listen to their so called (middleclass) dramas and has been a common feature of many British films in the past.