Interesteg

What makes it different from others?

Mjeteconer

Just perfect...

Fairaher

The film makes a home in your brain and the only cure is to see it again.

Cody

One of the best movies of the year! Incredible from the beginning to the end.

elizabethveldon

this film is a deeply moving, profound film discussing music, the choice between nationalist and religious collectivism, the power of forgiveness and the choices faced by japan in the post war period but it is far from unproblematic. that this film champions devotional over nationalistic collectivism in the main character and individualism over collectivism in the form of the soldiers themselves (as well as openly criticising the fascism which gripped japan with the fate of the troop on triangle mountain) is a great thing and aided the cause of pacifism in post-war japan.the use of music is likewise, as a musician, deeply moving and almost unique in film but i can not walk away from this film without feeling it is somehow problematic.the history of Japanese war crimes is well documented (the use of rape as a weapon of war, indiscriminate torture and murder) and this is side-stepped in the film. perhaps it is simply that this was too painful for japan to face up to at this period (indeed revisionist histories only began to occupy the Japanese mainstream in the 1970s) but it leaves a bad aftertaste for a contemporary viewer.i would however, even with these problems, recommend this film highly.

CountZero313

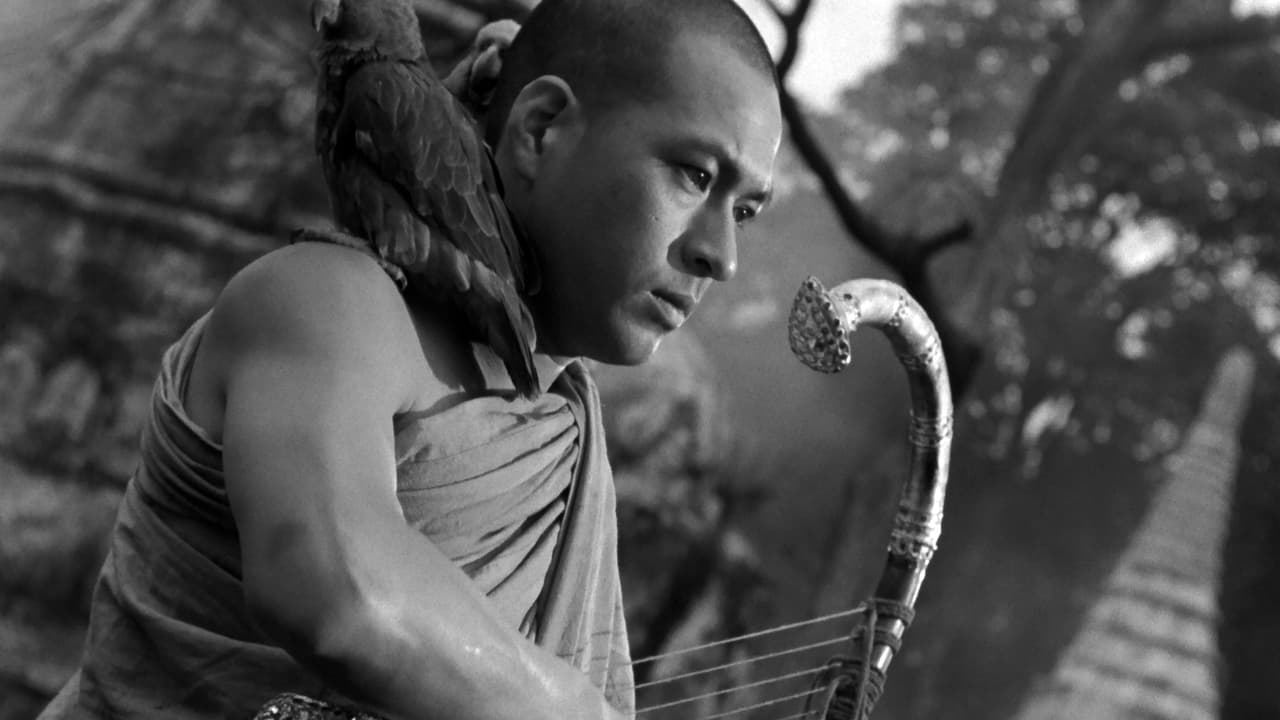

Towards the end of WWII, a group of Japanese soldiers struggle through the chaos of national disintegration, trying to reach the border through the Burmese jungle. Their Captain is musically trained and forms them into an ad hoc male choir in order to maintain morale. Foot soldier Mizushima plays the titular instrument and as such become a talismanic figure in the group. When he later disappears and suffers an existential crisis, his fate comes to obsess the group as a whole.Ichikawa's iconic piece contains a strong anti-war theme that survives beyond its 1945 setting. Mizushima's troop are timeless, soldiers dreaming of homes, wives, town festivals; clinging to nostalgia to guide them home and fighting on for each other rather than any greater cause inspired by the imagined national community. Much more identifiable with the period are the troop holding out against the British even after national surrender, fanatics looking to die for an Emperor who has forsaken them rather than return to their families and rebuilding of the community. Among these men, there are no songs.Mizushima's conversion from soldier-musician to selfless monk symbolises a state of reflection that follows all armed conflict. The film has been criticised for failing to confront the barbarism of the Imperial army, but this lack of identification with specific national failings is what gives the film a theme that transgresses to other cultures, conflicts and evils - the coming to terms with a life to be lived in the aftermath of horror. The flaws on the Yamato spirit may not be interrogated, but the atrocities of war are present, most visibly in Mizushima's encounter with the rotting flesh of fallen comrades being picked over by scavenger birds. The framing is impeccable, and those looking for a quintessential Japanese aesthetic will be surprised by the extensive use of closeups. The music is spare and suitably evocative of military camaraderie and frightened young men coping far from home. Mizushima's journey is both symbolic and highly plausible, as is the reaction of his brothers-in-arms. Great cinema in its own right, and at the very top of the tree in anti-war movies.

chaos-rampant

A lesson on how NOT to make a picture by one of the most celebrated Japanese directors of all time. I have no other way of explaining the ignominious debacle that is THE BURMESE HARP. This must be Ichikawa's 110 minute masterclass on how NOT to create a story. And it's genius for that.The basis of HARP's story is another return on the widely traveled path of the Hero's Journey. The mentor, the death and resurrection of the hero, the gift he returns with from the other world to bestow upon the world, everything the respectable Joseph Campbell taught can be found here.Where the movie falters is in substituting true dramaturgy and character motivation for saccharine sentimentality. Ichikawa goes straight for the jugular, his intentions to force the drama upon the viewer's emotions instead of letting it derive naturally from the premise and the character orchestration. Conflict, the most surefooted and ancient root in the heart of all storytelling, is forced via jumps in logic or simply produced on demand when the movie requires it.After a decent first 40 minutes and an almost excellent following 30 minutes, the movie proceeds to foreshadow its calamitous conclusion by turning the protagonist, a Japanese soldier turned Buddhist monk, into a sulking child. On his way back from a mission from which he barely survived he has the opportunity to witness the ravages of war firsthand. He returns to the previously appointed gathering point for the surrendered Japanese troops a changed man. Instead of rejoining his platoon to wait for their shipping back to Japan, he runs off and hides from them. His platoon spends the rest of the movie looking out for him, cajoling him and singing when the opportunity provides. Which is pretty darn often.Why did the private run off? Something to do with the harrowing images of unburied Japanese soldiers he saw on his way we understand. Let us make a small jump in logic and assume this is the first time a soldier engaged in war comes across such horrors. What is the specific character motivation that turns him into a sulking child? We never know. Ichikawa probably doesn't either as he has the platoon break out in song every 10 minutes until the final 5 minutes of the movie where he remembers he somehow needs to explain the protagonist's irrational behaviour. At which point the sergeant produces a very convenient letter written by the private, where in, what essentially amounts to little more than a voice-over narration, we are "told" a bunch of utterly vapid and bland clichés regarding "peace", "courage" and "easing the suffering of others".All great ideas to be sure but for the love of god man!! You can't tell us these things, we know already. You have to show, invoke the images and character actions that will enable us to arrive at those selfsame conclusions. Something Ichikawa himself did with the harrowing and soul-destroying FIRES ON THE PLAIN a couple of years later. Stacked against that monumental war drama, The Burmese Harp is feeble and puny, an elegiac ode on humanism that lacks the power of conviction.The black and white cinematography is great, it is after all a visual master of Ichikawa's calibre we're talking about. Is it surprising then that the most gripping sequence of the film is almost entirely silent? Ichikawa delivered his masterpiece with Fires on the Plain and with The Burmese Harp he shows how NOT to make a movie. What else could be expected of any director?

gelman@attglobal.net

This movie did not move me nearly as much as it seems to have moved others, perhaps because it resembles in certain respects other stories about World War II survivors. I can't help wondering how I would have reacted if I'd seen it when it was originally released. I suspect I would have found it much more affecting then than I do today. To be sure, the locale is more exotic than many other war survivor movies (though one suspects it was not actually shot in Burma). The gritty black-and-white film gives it a bit of a newsreel quality. But despite the left-over bones on the landscape, it does not make for a particularly powerful antiwar statement. All it really tells us is that Japanese soldiers were people too and one of them felt a pull to a more spiritual calling which he obeyed rather than return home with his wartime comrades.