Stometer

Save your money for something good and enjoyable

Hadrina

The movie's neither hopeful in contrived ways, nor hopeless in different contrived ways. Somehow it manages to be wonderful

Patience Watson

One of those movie experiences that is so good it makes you realize you've been grading everything else on a curve.

Winifred

The movie is made so realistic it has a lot of that WoW feeling at the right moments and never tooo over the top. the suspense is done so well and the emotion is felt. Very well put together with the music and all.

dbborroughs

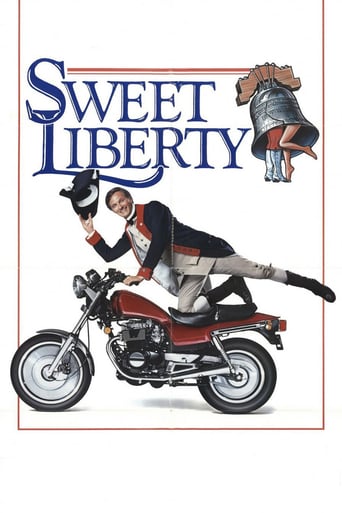

I like this very silly movie about the making of a movie set during the Revolutionary War. History takes a back seat to the backstage madness as film crew invades a small town in the American South... ...except that this film was filmed on Long Island. Living on the Island I get great joy watching all the technical gaffes in the film, only the lead characters cars have non-New York license plates, a Long Island Railway Train goes by in the background and on it goes. You don't have to have sharp eyes to see the errors, they are glaring if you know that they are there. They don't take away from the fun, they add to it since as Alan Alda's character quickly finds out, there is nothing real about making movies.The cast is great across the board, with everyone seeming to have such a good time its infectious. See this movie, its just a lot of fun.

£ynette

Alan Alda plays an historian who has written about an historical character. When his book is made into a film, the character he feels he knows so well is brought to life by an actress. The history he knows so well is translated into an "historical" film, with the fact gradually draining away. The film gently, lyrically plays on the interface between reality and fantasy.An irony is that in "Sweet Liberty" Michael Caine plays an actor who plays a character based on Banastre Tarleton, a British commander of Tory troops in America during the Revolution. In 2000, the German director Roland Emmerich made a film called Patriot in which Jason Isaacs plays a character based on Banastre Tarleton. In the Emmerich film, the fact has drained away and the British commit atrocities more appropriate to Germans in the Second World War.

drosse67

The "making of a Big Hollywood Movie" is certainly not a new idea for a comedy. Over the years there have been many movies like this--most recently David Mamet's "State and Main." What Alan Alda did for this movie is playfully comment on the state of the blockbuster (six years before Robert Altman's "The Player"). In 1986, the "blockbuster movie" was in its early stages. This film originally came out around the same time as Top Gun--case in point. Saul Rubinek plays the obnoxious Hollywood director (what? An obnoxious director?) who turns Alda's historical, and serious, book about the American Revolution into a romantic comedy, complete with big stars who take their clothes off. What makes this movie different from Alda's other films is that there are no serious undertones. Everyone is having a great time, and it shows. Michelle Pfeiffer, in one of her first starring roles, has rarely been funnier. Michael Caine struts his best comic stuff. And Bob Hoskins--how can you go wrong? The film has an obvious mid '80s feel (the music is terrible), and Alda's direction seems more suited for television, but this is still an enjoyable movie, less successful and acidic in its approach to Hollywood and its stars and blockbusters (compared to Sunset Blvd., The StuntMan, and of course The Player) but still worth watching.

stryker-5

Michael, a history teacher in a small East Coast town, has written a scholarly book about the American Revolution. Hollywood has decided to turn it into a movie, and cast and crew are descending on Michael's hometown to shoot the location scenes. The author gets a shock when he sees how is work is being revamped for the big screen. Alan Alda wrote, directed and stars in this good-natured romantic comedy. We are in classic Alda terrain here, the unspectacular small-detail world of domestic discord and couples who feel compelled to analyse their love lives. "You buy dishes together," ventures Michael, "and you invite people over. Then you talk about them in the bathroom while you're brushing your teeth." This is the microsmic universe that Alda loves to explore. Michael has three problems, all linked, which are currently exasperating him. Firstly, his aged mother (Lillian Gish) is very dotty and in need of care, something she steadfastly refuses to accept. Secondly, his lover Gretchen (Lise Hilboldt) won't cohabit unless he marries her. Thirdly, the Hollywood company which has come out east to make the film has desecrated his work by turning it into a lightweight (and historically worthless) love story. "I just wrote the book from which the movie has NOT been taken," fumes Michael. Faith Healey (Michelle Pfeiffer) is a method actress and a very big star. When in costume she is in character, even to the point of talking in 'colonial' English offscreen. Michael and Faith become romantically entangled, until Michael realises his mistake. There is no person at the core of the actress - just a creature voracious for the period detail that only Michael can supply. She was playing the part of a lover in order to draw from him what she needed. Elliott James is selfish and shallow, but incredibly charming and enormous fun to be around. A leading man who cares nothing for films, or even other people, he lives his life as one long party. Michael Caine parodies himself, and in the process turns in a commendable performance as the eternal matinee idol. Alda can certainly write. His dialogue always flows beautifully, and his understated characters are utterly believable. When Michael's 'authentic' 18th-century dialogue is spoken, the venerable cadences are gorgeous. Essentially, the film is about the artifice of movie-making. "Who really knows what happened a coupla hundred years ago?" asks the director (Saul Rubinek). The issue is, how far should film-makers go in disregarding historical truth in order to obtain audience approval? Films are, of necessity, separate and distinct from their source material - but in the trade-off between authenticity and popularity, where is the balance to be struck? A New England community such as this one is fiercely proud of its heritage, and indeed very knowledgeable about it. The guys who stage War of Independence re-enactments know in minute detail about the manoeuvres, skirmishes, equipment and ammunition which constituted real events and which form their living culture. It is an affront to these people for ignorant West Coasters to play fast and loose with their sacred lore. In a film about the artifice of film, Alda makes intelligent use of cinema tricks and conventions. Elliott insists on doing his own stunt work - and yet for his triumphant fall into the pond, Michael Caine is doubled by a stunt man. The blizzard scene is shot in glorious New England sunshine. The steadycam revolve shot which marks the romantic climax of the 'film' film is repeated at the romantic climax of 'our' film. With delicious malice, Alda satirises the internal dynamics of cast and crew. Bob Hoskins is the writer with no brains and no class who helps Michael understand the power struggles within the movie's little community, and how best to exploit these envies and vanities in order to get what he wants. Sword fencing is a subtle metaphorical strain running through the film. When we see Michael and Gretchen fencing in the opening scene, the play-fight represents the involvement and the conflict inherent in their relationship. The 'audience' of fencing masks on the wall stands for the public attention to which they will shortly be exposed. Newly-arrived film crew members unload Scottish broadswords, showing from the outset that there will be brash disregard for authenticity. Elliott and Michael sublimate their clash of wills in a protracted sword duel. We are told (and shown) that teenage cinema audiences expect three things in a movie: defiance of authority, destruction of property, and nudity. Alda's film complies with the formula, but also intelligently undermines it. Gretchen's quiet jealousy is excellent, as is Michael's stiff back, expressing vehement disapproval without moving a muscle. A film can stimulate eye, ear and intellect: it doesn't have to follow shallow formulae. If the action climax is a little too smug and convenient, Alda can be forgiven. He is making smart, literate films for grown-ups. Long may he continue.