Matcollis

This Movie Can Only Be Described With One Word.

Kaydan Christian

A terrific literary drama and character piece that shows how the process of creating art can be seen differently by those doing it and those looking at it from the outside.

Ezmae Chang

This is a small, humorous movie in some ways, but it has a huge heart. What a nice experience.

Cassandra

Story: It's very simple but honestly that is fine.

tieman64

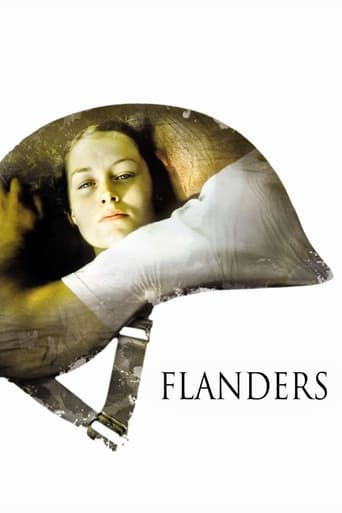

"Perhaps when we were raping her we looked at her as a woman. But when we killed her, we just thought of her as a pig." - Unknown SoldierBruno Dumont preaches to the converted with "Flanders", a film which merges Brian De Palma's "Casualties of War" with Stanley Kubrick's "Full Metal Jacket".The film's first act takes place in a monotonous world of rural villages and lifeless arable land. Using static shots, Dumont spotlights various listless, expressionless characters. Significantly, when energy is expended, it is only to have sex. Dumont's cast resemble livestock as they copulate in the mud.Like Kubrick and De Palma, conflict stems first from the phallus. Here, a Belgian farmhand called Andre has sex with a local girl called Barbe. It's a pathetic act, a moment where animal drives and emotions confusingly conflate. Afterwards, they're left unfulfilled, the social and biochemical allure of sex giving way to something more banal. It is only when Barbe sleeps with another man in her village that Andre reassess his relationship with her. We don't yet realise it, but revenge fantasies and feelings of psycho-sexual humiliation are bubbling in Andre's head. Now aware that Barbe is desired by others, and that he has no claim over her, Andre acquires a newfound desire to conquer, dominate and spread his seed. The film cuts to an unnamed Middle Eastern country, the playground of Andre's psyche. Here he witnesses men killing children and soldier's forcing themselves upon a young woman, a scene which echoes not only De Palma's "war as rape" narratives, but Kubrick's symbolic snipers and hookers. Andre then witnesses the raped woman's vengeful response. Back home, Barbe is aborting a baby.The film's final act is where it breaks free of most war movie conventions. Andre returns from war not traumatised, but with a newfound sense of "humanity". Realizing the dark contours of his desires, his own libidinal drives, Andre sees Barbe for the first time in a new light. Whilst throughout the film everyone views Barbe as a whore, he sees her now as something else. Film's first words: "s**t" and "f**k". Film's last words: "I love you." Like Dumont's "Humanity", "Flanders" paints an exodus away from the corporeal, the bestial, the crude wants of the flesh, and toward what at first seemed like a spiritual impossibility. The film's title alludes to the killing fields of World War 1, but its imagery conjures up modern images of Iraq, Afghanistan and various American Crusades across Latin America and the Middle East. Scenes in which soldiers travel on horseback evoke the legacies of Western expansion.Typical of Dumont, the film is a work of extreme minimalism. Every action, gesture, shot, movement and line of dialogue is stripped down to an almost Bressonian essence. Only the "essential" remains. Viewers unwilling to read the film's whispers will find nothing to hold their interest. Some have said that the film is contemptuous and disgusted by humanity. This is not true. One can argue, however, that Dumont, like most New French Extremists, hates his medium. That he holds the belief that cinema can convey truths only by first rejecting the medium's aesthetic possibilities and gifts for enchantment. The film's distancing effects thus feel smug and self-congratulatory.Sexual drives and issues of war-rape tend to be left out of most war films, despite sex being at the core of most violence (as I write this, it has been learnt that hundreds of Sri Lankan women were raped by soldiers during the 2009 Civil War, a fact which the local government subsequently covered up- similar things continue in Iraq). Rape is a form of trans-generational revenge and punishment. It is an extension of misogyny, the genocide mentality, the wish to extinguish the enemy and feelings of nationalistic superiority. The undermining of the enemy's familial, social and national bonds by humiliating females, by creating life-time scars in women's bodies and minds and by socially stigmatising the enemy, does not only comprise psychological warfare, but is a direct extension of the gun and the phallus. In a patriarchal society each rape symbolises, not only abject defeat, but the impotence of the Other (male or female), now rendered submissive. The term rape is also used to denote the occupation of a territory or a town (e.g. the rape of Nanjing) and has even leaked into the computer gaming vocabulary of children ("raping" opponents). Feminist explanations of sexual torture stress that men abuse power and engage in games of sexual dominance (humiliating and subjugating women etc) as a means of reinforcing their masculine identities. Under such assumptions, men stripped of civilisational inhibitions reveal their "inner desires" with and during war-raping. This view is supported by the fact that the vast majority of rapists in war are not mentally disturbed. They are 'normal' men, drafted or volunteers. But while it is true that male sexuality is potentially more aggressive than female sexuality, also in times of peace, one must realise that this aggressiveness is cultivated and intensified through the institutional misogyny of the military establishment (and exploited during racist wars). Under such circumstances, many more men rape, even those who would never consider raping a woman during "normal" times. Here, the responsibility for atrocities lies with leaders, who engender or outright sanction such acts. "Flanders" is far too esoteric and will alienate those most requiring its message. Dumont fails to capture the sparse spirituality of a Tarkovsky, Bresson or Antonioni, despite channelling such a tone well with "L' Humanité". The film is somewhat derivative of "Full Metal Jacket", a film which better conveys the sheer misogyny of bootcamp (and after), and which better points to the future landscape of wars: a world of humane, clean kills, sexism, murder and racism rationalised away by brainwashed men and women as ethics administered via trigger.7.9/10 - Worth two viewings.

pdee-1

I gather French movie makers receive subsidies to produce French language movies - is this true ?It would help to explain the number of tedious pot boiling French movies. There is little commercial incentive - just put something together and collect the check from the government ?I am always suspicious of movies where and when people just aimlessly wander around or indulge in desultory conversation (if it could be called conversation) They tried to insert some action into the film - not very convincing. A military expert would come down hard on troops herding together in a gaggle under fire instead of dispersing. And a helicopter landing directly into an area under small arms and grenade/mortar fire ?(and getting away without coming under fire! Lucky guys! )

dromasca

What is surprising in this film is the way the director uses a very simple minimalistic style of telling a story to cope with one of the most important themes of the contemporary world - the involvement of the young people in Western countries in wars that happen in the third world. This is the story of two young men from some rural place in Northern France or French speaking Belgium who are sexually involved with the same girl before being sent to fight a war in a remote Islamic country. The girl has her own mental problems and has an abortion while the young men face all possible horrors of war, face death, commit and are subjected to unimaginable violence. All is told in very simple, well filmed and clear images, and this creates a strong emotional impact. With simple cinematographic tools the director sends a message of distress and pain about the conflicts human beings are subjected to in the world today. Worth watching.

matt-szy

Bruno Dumont does not like expressions on people faces. The characters in his films do not act with facial expressions. Instead they move and talk and look around like any real live person might do except with no emotion. This is called minimalism. Dumont directs his actors to portray as minimal emotion, reaction, sensation as possible. This does not mean he does not take the face into consideration. No, no. It is in the face that we can see the person, what they have been through, how much they might have suffered, experienced, etc. In fact, Dumont chooses faces well. And what Dumont does better than choose the faces of his actors is he creates a sense of emotions, internal confusion, and unguided motivation in a world that exists solely between the boundaries of our vision and the outermost layer of our eyes. We see this in Flandres.What could and usually is, in cinema, a way to convey emotions is by framing facial expressions which usually follow or/and precede dialogue. Dumont simplifies this process and leaves any emotional identification more up to interpretation, and consequently having us rely on our own feelings as viewers to understand the characters depth rather than understanding the characters feelings – for as it seems, for Dumont, feelings are a rather difficult thing to express.Dumont does this by montage. The main character, Demester, a weird but thoughtful looking guy, is with the girl he does not call his girlfriend, Barbe, on the day before he leaves to war. They are sitting before a bonfire in the French country side during winter. They are met by the guy who the Barbe recently met at a bar, Blondel, a pretty looking boy. Barbe and Blondel have sex right away in the parking lot. Demester watches this happen but does not react. Both Blondel and Demester are going to war and will be in the same brigade. Barbe is sitting between them. They simultaneously lay back in the grass. Barbe takes turns kissing them, leaning from one side to Demester then to Blondel, telling them how much she will miss them both. Demester sits up. He stares off in the distance, detached from the situation. After seeing his blank face for a while we cut to a silhouette of a tree in the distance with the flat and frozen winter country in the background. The tree has no leaves, it's branches reach out wildly in all directions. A few moments pass. And cut.Sex in Dumont's films is often brutal and sad, and is always short. The girls never appear to get pleasure out of sex and the guy is always mechanical and numb. Demester and Barbe walk silently for some time to an isolated grassy area where they do not kiss, Barbe only pulls down her pants and says, "do you want me?" at which point Demester gets on top of Barbe. It is as though the characters in Dumont's films are simplified to their basic animal needs and that sex is the only means to some deeper connection. In "The Life of Jesus" the main boy and his girl are often in the background of a scene kissing at a slugs pace with no elevation of excitement, receiving no reaction from friends nearby, frozen in a suction like mouth to mouth. Likewise, in a scene in "Humanity" sex is shot from a wide angle in a long take revealing the banality of the act.Shots of repetitive motions often last for awkwardly moments. As Demester is plowing though a field – he is a farmhand – with a tractor a close up of the blades slicing through mud and dirt underline the mere ugliness and mechanical repetitive nature of things. Shots and repetition like this persist in all Dumont's films. In "The Life of Jesus" it is the sight and sounds of the Scooters, the monotone kissing of the young couple, and in "Humanity," it is the legs of a man riding a bike, among others, which the viewer is forced to watch obsessively.Above all Dumont is a moralist, however subtle. He shows us the thoughtlessness of our actions. Flandres is, in short, about a guy who does not know if he loves a girl. He leaves to war, and there he rapes, kills, witnesses killing, leaves behind a fellow soldier in order to save himself, gets lost, and is himself nearly killed in a few situations. His life is spared not by any of his good deeds, for there are few, instead his life is spared by none other than blind luck. He is not special. He is just lucky. And after having returned home to his little simple life in the French countryside, unable to verbalize this experiences to Barbe, the only words he is able to conjure up, after some difficulty, is I love you.