Tedfoldol

everything you have heard about this movie is true.

TrueHello

Fun premise, good actors, bad writing. This film seemed to have potential at the beginning but it quickly devolves into a trite action film. Ultimately it's very boring.

Sienna-Rose Mclaughlin

The movie really just wants to entertain people.

Philippa

All of these films share one commonality, that being a kind of emotional center that humanizes a cast of monsters.

valadas

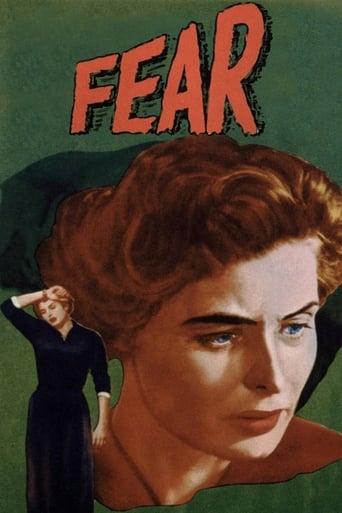

Terrible indeed and admirably performed by that beautiful woman and great actress named Ingrid Bergman, a story directed by her husband the also great film director Roberto Rossellini. A married woman whose husband is a prominent professor has an adulterous relationship with another man. Suddenly a former lover of that man appears and begins to blackmail her demanding high money sums and threatening to tell everything her husband. She is then upset by fear and begins to cede to blackmail. Later we learn that this was planned by her husband with perhaps not very clear intentions. When she knows this she is psychologically destroyed and plans to kill herself of which she is saved by her husband at the last moment and they show that afterwards they love each other. Of course it is psychologically possible that a woman loves two men simultaneously although in different ways (or a man two women). The movie is therefore authentic. Although not exactly a masterpiece this movie is worth to be seen for its intense dramatic atmosphere in what concerns Ingrid Bergman's role and the very good performance of actors and actresses.

Horst in Translation (filmreviews@web.de)

"Non credo più all'amore (La paura)" or simply "Fear" is a co-production between West Germany and Italy that resulted in a black-and-white movie from 1954, so this one is already way over 60 years old. It was co-written and directed by Roberto Rossellini and the main character is once again played by his (then still) wife Ingrid Bergman. According to IMDb, this one is slightly longer than 80 minutes, but the version I saw was even 10 minutes shorter, so it is not a long movie at all and there exist several versions. The original work this is based on is by Stefan Zweig and I suggest the recent Maria Schrader video to everybody who is curious about the author. Zweig's involvement may also have to do with the film having the main language German, but I am not too sure if this is accurate looking at the film's title and also the cast. At least the version i watched was exclusively Italian with English subtitles.This is a story about fear as the title already states and relationship struggles play a major role as well as in many other Bergman films. Moonlighting and blackmailing are crucial components in the story here, but lets be honest, all in all it is really a major Bergman showcase as well and honestly beyond her acting I think the story is not as good as it could have been. If you are a Bergman fan, you will probably enjoy this one as she has several scenes in which she can shine, but I myself have seen not too much from her yet and what I saw here does not really get me curious about her other works or Rossellini's. I myself was glad that the film was over relatively quickly as I cared little for the story or character(s) eventually. I give it a thumbs-down and like I said I only recommend it to the very biggest Bergman fans.

chaos-rampant

This appears to have been mysteriously lost when the history of cinema was being written. It is a hard film to place anyway. Rossellini had hit his stride and was on his way out of the public mind, it's far from the neorealism he became famous for, it's not lurid enough to pass as noir. Antonioni had not yet arrived at Cannes to reinvent the vision present here inside a modernist framework. All this is made worse by the meddling of Italian distributors, anxious for ticket sales. Subsequent generation of film-watchers would have stumbled (if at all) upon something too small, an unfulfilling, incomplete affair.But like so many of these flawed pieces, it is endlessly fascinating. Rossellini was blessed with a gift; his work is not the result of a fiery intuition bursting forth, but of a studied, assured awareness. Grasping and what is grasped become one in his films. It's hard to conceive the great Antonioni, who was so inspired by him and who really opened up what Rossellini contained within a religious language, without a film like this or Stromboli. From a distance, it's simple enough: a story of marital infidelity (which, like Stromboli, inadvertently resonates out of the film and into the illicit love Bergman and Rossellini shared), about a woman's descend into paranoid fear and delusion. An image of the fractured self, painfully learning the lesson that makes whole. Between grief and nothing, as Faulkner would have it.But such richness of appearances. How inner disturbance seeps outside; in the piano concert scene, notice how the music swells from placid to nerve-wracking crescendo. Notice the downpour that accompanies the razorblade-edge crisis of conscience. When the noose begins to be pulled tight around her neck as the husband inquires about a missing ring, faces are drowned in a sludge of shadow like out of Weimar noir.Further inside; the threatening image of the ogre-father to be appeased, with the daughter and wife one before his gaze. He holds the keys to both punishment and forgiveness. The suffering and humiliation born from delusion and desire, and how they trap the soul in chimeras.The other thing I want to stand on is what was originally intended of the compromised vision we have available. Rossellini's daughter is reportedly working to restore the original, a time-consuming affair in most cases, but until then this is all we have.A fishing scene is missing and tiresomely expositional monologue is added in two scenes; from what I could gleam, the opening and finale. Both marvelous renditions of wanderings through night streets, itself an aesthetic ahead of the times. And then the most important thing of all, that pushes the film into cinematic apotheosis. The finale, which the distributors meddled to turn into a cloying sentimentality that ensures closure and balance.Rossellini intended the film to end with a suicide attempt (we see the prelude, with Irene writing her suicide note), but then she thinks of her children and returns home. Rossellini shot footage of this. The footage comprises two shots; one is the shot filmed from inside a car crossing idyllic countryside to reach the remote cottage house, the other is Irene in her favorite armchair as her childhood nanny soothes her.Both these shots were repeated earlier in the film, when Irene and her husband first get to the cottage. To the place where Irene grew up, where her children are now. Childhood comfort is possible there, as refuge from the punishing dead-ends of adult life. We see her, as again in the finale, reclining on her armchair with her nanny by her side.So we have in th end Irene anguishing over her suicide note on her desk; then her regressive trip back into the place of comfort. Whatever end we get in the coming restoration, this is one of the most potent finales in pre-60's cinema, the suicide all there disguised as the journey back.

klauskind

Whenever I see La Paura I think of it as a companion piece to Eyes Wide Shut, or maybe it is the other way around. Adultery makes both films tick but in different ways. I think Phillip French was right on the money when he pointed out a Wizard of Oz thing in Kubrick's last work. Like Dorothy, Tom and Nicole go through fantasies and nightmares and at the end Dorothy's reassuring childish motto "there's no place like home" is ironically updated to the adult circumstantial adage "there's no sex like marital sex". Kubrick's take is intellectual, he never leaves the world of ideas to touch the ground. He taunts the audience first with an erotic movie and then with a thriller and refuses to deliver either of them. He was married to his third wife for 40 years, until he died. Rossellini was still married to Ingrid Bergman when he directed La Paura; they had been adulterous lovers and their infidelity widely criticized La Paura is a tale, a noirish one. The noir intrigue is solved and the tale has a happy ending. The city is noir; the country is tale, the territory where childhood is possible. The transition is operated in the most regular way: by car, a long-held shot taken from the front of the car as it rides into the road, as if we were entering a different dimension. Irene (Bergman) starts the movie: we just see a dark city landscape but her voice-over narration tells us of her angst and informs us that the story is a flashback, hers. Bergman's been cheating on her husband. At first guilt is just psychological torture but soon expands into economic blackmail and then grows into something else. From beginning to end the movie focuses on what Bergman feels, every other character is there to make her feel something. Only when the director gives away the plot before the main character can find out does he want us to feel something Bergman still can't. When she finds out, we have already experienced the warped mechanics of the situation and we may focus once again on the emotional impact it has on Bergman's Irene. In La Paura treasons are not imagined but real, nightmares are deliberate and the couple's venom suppurates in bitter ways. Needless to say, Ingrid has another of her rough rides in the movies but Rossellini doesn't dare put her away as he did in Europa 51, nor does he abandon her to the inscrutable impassivity of nature (Stromboli). His gift is less transcendent and fragile than the conclusion of Viaggio in Italia. He just gives his wife as much of a fairy tale ending as a real woman can have, a human landscape where she can finally feel at home. Back to the country, a half lit interior scene where shadows suggest the comfort of sleep. After all, it's the "fairy godmother" who speaks the last words in the movie.