Kailansorac

Clever, believable, and super fun to watch. It totally has replay value.

SanEat

A film with more than the usual spoiler issues. Talking about it in any detail feels akin to handing you a gift-wrapped present and saying, "I hope you like it -- It's a thriller about a diabolical secret experiment."

Micah Lloyd

Excellent characters with emotional depth. My wife, daughter and granddaughter all enjoyed it...and me, too! Very good movie! You won't be disappointed.

Griff Lees

Very good movie overall, highly recommended. Most of the negative reviews don't have any merit and are all pollitically based. Give this movie a chance at least, and it might give you a different perspective.

JohnHowardReid

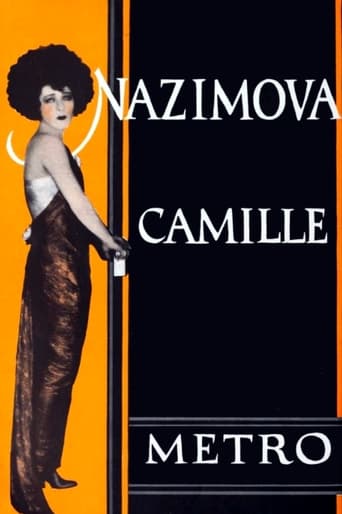

I never thought of Rudolph Valentino as a dull actor, but that's just what he is in this dreary account of Camille. As if to make up for Valentino's stodgy performance and his amazing lack of charisma, Alla Nazimova has gone to the opposite extreme, indulgently over- acting and sporting the most bizarre hair style I've ever seen – either in a motion picture or even in real life. The movie is directed by the none-too-talented Ray C. Smallwood (who actually left movie directing behind him in 1922, but then returned to Hollywood 22 years later as a special effects man!). Smallwood was obviously under the complete control of producer/actor Nazimova who hogs the camera like mad from start to finish. She really revels in what seems like a continuous, never-ending series of really bizarre close-ups. I certainly hope that Nazimova's other movies are considerably less dreary. I have seen the Kodascope cutdown of Salomé in which she plays the title role quite ably. But Camille, I feel, is a movie she would rather forget. Even her own performance is remarkably inept. And as for that high-hat hair style!

secondtake

Camille (1921)I stumbled on a great clean copy of this packaged with the more famous Garbo talkie version from 1936, and it was interesting mostly as a comparison. Here for the first time I got to study the famous Rudolph Valentino (the "matinee idol" of the period). And in the leading role as the modernized Camille was Alla Nazimova, a Russian actress with serious aspirations and some success in the era.The film is a stubborn one to like, however. While not badly made, it has the stiff and sometimes plodding editing, scene to scene, that implies an audience that might not keep up with a more sophisticated treatment. (And more complex editing was common by 1921, for sure.) The acting, silent as it is, is false enough often enough to push a modern viewer off. Nazimova has this fabulous and distracting giant hairpiece on, for some reason, as if to show she's truly wild, but her acting is almost too serious for the fun she is meant to inspire.The set design is a wonder in many ways, having a modern flair that precedes Art Deco and might interest fans of that mid-20s style. The camera, however, is often satisfied to center the scene and sit and watch the events. Bitzer (with Griffith) knew the dangers of this years earlier, and little known director Ray Smallwood is clearly not making the most of some very dramatic moments.The story, in brief, is about a spirited young woman who is at the age where she must marry to survive, and she falls between a rich, dull count and a handsome, adorable common person (Valentino). What plays out is something very unfamiliar to Western women in our era, because the main woman (who is called Marguerite) is trapped by really needing a man to support her, period. True love with a relatively poor chap just won't do, and yet of course true love is true love, and Valentino promises to support her one way or another. But his (of all people) father interferes and and basically dashes true love on the rocks.The end is unremittingly tragic, the camera again centered on the final scene.See it? No, I'd so not, unless you have some deep interest in either the story or one of the main actors. The plot is based on a Dumas classic from 1848, and is most famous for having inspired the great opera, La Traviata. If you want a quite good movie on these events, see the Garbo version.

rdjeffers

The Dark SwanSaturday, July 14, 5:45 p. m., The Castro, San FranciscoForbidden love, betrayal and tragic self-sacrifice resonate throughout Alexandre Dumas' popular novel La Dame aux camélias, published in 1848. The story of a young aristocrat, who falls in love with a courtesan, the "Daughter of Chance," has appeared in a multitude of adaptations on the dramatic stage, in film and opera. Notable versions include Verdi's La Traviata and a popular English stage adaptation Camille, the subject of many films, first in 1907 and most recently in 1980.Exotic Russian actress Alla Nazimova developed and starred in this 1921 Metro Pictures production with Rudolph Valentino. A student of the great Stanislavsky, Nazimova first appeared on Broadway in 1906, introducing Ibsen and Chekhov to the American theater while starring in The Cherry Orchard, Hedda Gabler, A Doll's House and many others. Her immense popularity led to a film career, beginning with War Brides (1916) for Selznick Corporation, followed by a succession of financially lucrative films at Metro. During this period Nazimova became an influential figure within the developing 'Café Society' of actors, producers, writers and technicians who lived and socialized in the rolling hills above Hollywood.Nazimova's Camille showcased the talents of brilliant young scenarist June Mathis and production designer Natacha Rambova, who created unique, unconventional art deco sets and costumes for the film. Handsome young Italian Rudolph Valentino was cast as Armand, Camille's lover, following his work in Rex Ingram's The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse and The Conquering Power, both scripted by Mathis. The wave of intense popularity that followed Valentino for the rest of his abbreviated life began in 1921. Nazimova brought a dark elegance and restrained intensity to a character previously identified as cheerfully compliant.While Nazimova came to film late, forty-two when Camille was released, and the appreciation of her talent was never fully realized on film, she did exert a planetary influence on many younger performers. Her smoldering, feline sexuality is visible in the thin veneer of sophistication and moody avoidance masking Mae Murray's utter panic in The Merry Widow (1925), and Carole Lombard's haughty, posturing, indifference in Howard Hawk's Twentieth Century (1934).

briantaves

Alla Nazimova (1879-1945) is one of the female pioneers of the silent cinema. While her name endures, her movies are seldom seen, and indeed many of them have been lost altogether. She was a native of Russia, born of Jewish parentage as Adelaide Leventon, and studied with Stanislavsky. She came to the United States in 1905 and gained fame for her skills as a dancer, and an actress, conquering Broadway and becoming renowned as the era's greatest interpreter of the plays of Ibsen. Her stage fame brought about her first appearance on screen in 1916, and although her subsequent Hollywood starring career spanned a brief ten years and only seventeen films, her influence was profound. Nazimova also dominated the making of most of her films, often functioning without credit in all three primary capacities of producer, director, and writer. In addition to her films, Nazimova became the first of the movie queens to establish a virtual Hollywood court at her home (later known as "the Garden of Alla"), largely of emigres, who were dedicated in many different ways to the art of the cinema. Rudolph Valentino became part of this group in 1920, when Nazimova was forty and at the height of her fame and power. Through the creative community she gathered around her, she helped form the milieu that inspired what Valentino hoped to do in movies. Under the influence of Nazimova and others, Valentino came to realize the artistic potential of the cinema, and sought to ally himself with talented individuals. Valentino had spent several years moving up from a supporting player to his breakthrough role in THE FOUR HORSEMEN OF THE APOCALYPSE (1920). Before the release of THE SHEIK in 1921, with Valentino in the title role that would secure forever his star image, he had played leading roles in a number of disparate films. It was in this interregnum that Nazimova selected him to star as the true love Armand opposite her in CAMILLE, a property she had chosen to make.CAMILLE, distributed by Metro, was her last film for a studio; she selected the property, and the scenario for this modern-day version of the Alexandre Dumas fils classic was written by June Mathis (1892-1927). The third significant woman contributing to CAMILLE was the film's art director, Nazimova protege Natacha Rambova. Unlike Nazimova, despite her name Rambova was not an expatriate, but the daughter of a wealthy Utah family (born Winifred Shaughnessy) who had adopted the name Natacha Rambova before she met Nazimova. By the time of CAMILLE, Rambova and Valentino had fallen in love, having met one another through Nazimova. Part of his attraction to Rambova was his recognition of Rambova as a woman of rare intelligence and ability as well as beauty, with whom he fell deeply in love. In collaboration with Rambova, he sought to make films that were more than commercial product, but studio moguls bitterly resented Rambova's intelligence as a woman and a wife, and Rambova found herself and her marriage to Valentino smeared by gossip. Ultimately, the strains would drive Valentino and Rambova to divorce a year before his sudden death in 1926. CAMILLE richly displays the range of Nazimova's acting ability, at once varied, highly stylized, and realistic in the role of Marguerite Gauthier. Perfectly complimenting her performance is the mise-en-scene. For instance, ovals continually reappear around Nazimova in closeups, accented by the many iris-in shots, all evoking Marguerite's symbol of the camellia. Rambova's designs, both linear and ornamental, highlight the ubiquitous circular motifs through a myriad of similar background shapes, such as windows and doors. There are many typical European touches throughout the melodramatic narrative, such as the silhouettes of the dancers seen through arches in the casino. Snowfall represents Marguerite's illness, while her temporary recovery under Armand's care is matched by the similarly white, happy blossoms of spring and the sunlight. Marguerite perceives the two lovers as akin to the protagonists in Manon Lescaut, after she receives the volume as a gift from Armand, the only token she has of her relationship with the poor student. Armand's father demands that Marguerite, as a woman with a scandalous past, renounce Armand for the sake of his own future, and that of his sister. Forced to make the ultimate sacrifice of her love, a typical convention of films centered on female protagonists, Marguerite returns to her old life, hoping Armand will come to hate the memory of their time together. Marguerite's death scene extends screen time, and is presented both through her own last blurred visions, as well as how she is seen by her friends and the callous men violating her bedroom to scour it for valuables to pay her creditors. The editing captures the many changes in emotion and the frequent intercutting between the sad present and the fond memories of past idylls with Armand. CAMILLE succeeds as an example of the art film, and yet one that also retains the fundamental elements of melodrama that appeals to audiences, successfully melding both aspects in a manner that the more avant-garde Nazimova-Rambova collaborations do not achieve. CAMILLE was not their first joint effort; Rambova had previously designed Nazimova's BILLIONS (1920), and later worked in the same capacity on Nazimova's A DOLL'S HOUSE (1923) and SALOME (1923). After CAMILLE, however, Nazimova's popularity was diminishing, and she lost a fortune on SALOME, an independent production she financed which saw minimal release because studio executives believed it would be too highly stylized for audiences. Nazimova lost her prestige in an industry dominated by those who saw film in strictly commercial terms, and for whom Nazimova's talent was excessively offbeat. The remainder of her movies were made for much-needed income, without the control she had once enjoyed. She resumed acting on the stage, until returning to Hollywood in the last few years before her death in 1944. One of her first comeback films would be, ironically, the 1942 remake of Valentino's silent film BLOOD AND SAND.