Joanna Mccarty

Amazing worth wacthing. So good. Biased but well made with many good points.

Sameer Callahan

It really made me laugh, but for some moments I was tearing up because I could relate so much.

Jenna Walter

The film may be flawed, but its message is not.

Calum Hutton

It's a good bad... and worth a popcorn matinée. While it's easy to lament what could have been...

CanadianCinephile

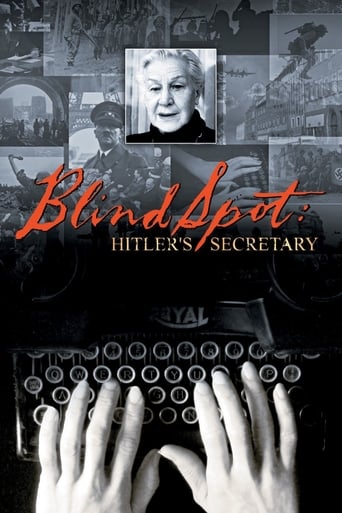

Some documentaries are overcooked showcases of sleek editing techniques and computer graphics, while others are rather slim in stature. Blind Spot: Hitler's Secretary is an unfussy motion picture that consists entirely of about 90 minutes of interviews with Traudl Junge. To overlook the barebones testimony of Junge, Adolf Hitler's youngest personal secretary, would be a mistake.There are some who may find the hour and a half to be lacking in bells and whistles, but there's much more going on here than meets the immediate eye. In our day and age of attention deficits, real or imagined, it is often hard to convince people that they really ought to listen to what Junge has to say when she's not saying it over an explosive musical score or in 3D.In any event, directors André Heller and Othmar Schmiderer present Junge sitting in a chair in her home and only cut away a few times. The cuts are used for different reasons. One particular cut shows Junge watching the main feed of the interview. She offers a little extra commentary over what we've just heard.Junge's memoir, Until the Final Hour, was used as a basis for one of my favourite motion pictures of the last few years, 2004's dazzling Downfall. In Blind Spot, we learn more about what it was like during those final years of Hitler's power and life. Perhaps more importantly, we learn about Traudl Junge and how she was swept up into such profound evil without knowing the details. Spellbound by Hitler's charisma and by, at least in part, her daily routines, she held reality in her blind spot.There are some who will mumble over what they feel is a mere news interview, but they tragically miss the depths of Blind Spot. Here is a motion picture that should be a motion picture. The depths of Junge''s consciousness are raw and torn apart. Her facial expressions, her tears and her agony are spread across these 90 minutes and present an emotional cavern that few other movies would have dared to explore.It is the unflinching, unadorned nature of Blind Spot that grants it the power it needs to carry on. It is the silent moments, too, and the space between words that speak volumes. It is the small moments, described in almost endearing detail, that display what happened in the bunker and during Hitler's final hours in bright, vibrant colours. We don't need a score, we don't need graphic assistance. We carry it, I think, in our mind's eye.The trouble with an unscripted masterwork like Blind Spot is that we can't see the bottom. There's no direction for Junge to follow, other than to sit in a chair and talk about her experiences. When she wanders off on tangents, we go along and the purpose engrosses us. As she begins to talk about Hitler's affection for Blondie, his dog, we marvel at the detail. Later, when Junge explains how Hitler poisoned his dog during his final maddening moments, the circle closes.With most moviegoers, even those brave enough to chart the waters of documentary films, used to a line-up of talking heads and a barrage of information, Blind Spot proves deeper than most with just one individual voice carrying on. As a true sign of fascination, I was left with more questions. Just as I wanted more out of hearing my grandmother talk about her life experiences, I wanted more out of Traudl Junge. Perhaps this was all she had to give, though, as she passed away in February of 2002 at the age of 81 (the same day the film premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival).Before she died, Junge apparently said "Now that I've let go of my story, I can let go of my life."

Ralph Michael Stein

Traudl Junge, one of the few young women who served as Hitler's secretaries during the war and through the cataclysmic demise of the Third Reich and its founder in a besieged Berlin bunker, died on the day this documentary was premiered. Junge was no stranger to interviews and the camera. In fact this articulate woman appeared in several documentaries long before this minimalist film in which she is the only person on screen and, in fact, is the sole speaker except for a few questions posed by an off-screen interlocutor.Because of her typing skills she was offered the position of working directly for Hitler by the fuehrer himself. This brought her into close, indeed daily, proximity with high-ranking Nazis as well as characters such as Eva Braun and the family members and hangers-on of the regime. Junge herself maintains that she was apolitical and viewed the job offer as an exciting opportunity, not a chance to serve the Party or its ideology.Junge frequently refers to Hitler as a criminal and ponders her own involvement and whether she is guilty of anything because of her association. She maintains she knew nothing about the extermination camps and remarks that Jews were rarely referred to in any context at Hitler's headquarters. Some have feared that her comments, clearly not disingenuous, will fuel revisionist Holocaust deniers in their sick quest to absolve Hitler and the Nazis. In fact, however, many other accounts have long supported Junge's statements that the fervent anti-Semitism of the Nazis wasn't on display for those visiting or working with Hitler. She recalls that one woman visitor asked Hitler about the cruel packing of Jews into trains for deportation and he angrily told her, basically, to mind her own business. She was never invited to his headquarters again.

The one-time secretary admits she initially much admired Hitler who often addressed her and the other female office workers as "my child ("mein kind"). She describes his manner as gentle and very different from the filmed rally and Reichstag harangues all today have seen. In fact Junge never attended any of the military conferences held near where she worked where Hitler's histrionic displays were always on offer and where his screaming, berating of generals was routine.Junge was present on 20 July when the attempt on Hitler's life failed and she saw him in tattered clothes shortly after the bomb explosion. Her closest association with the Third Reich's leader came during the final days when the Red Army slowly encircled and then took Berlin. Her description of life in the bunker and Hitler's slow slide into defeatism is neither new nor analytical - there are many other accounts of Hitler and his entourage in the bunker. But she speaks with a clear memory, cogently and not unemotionally.Junge is strong voiced and clear-minded and she betrays little deep emotion. The one point where she loses her composure is as she describes getting food for propaganda minister Goebbel's six little girls, the oldest only ten, while their parents prepared to murder them in the belief they would have no worthwhile life after the Nazi defeat. A microcosm of Nazi madness, the killing of these six innocent children has always disturbed me.Directors Andre Heller and Othmar Schmiderer employed a wholly minimalist approach. Their subject occupies the screen entirely during the interviews which spanned a number of sessions. They decided, correctly in my view, to let her narrative totally dominate where many documentarians would have interweaved film illustrating the events she experienced. This approach may bore some but listening to Junge for eighty-plus minutes actually is a very absorbing and intense experience.A book containing Junge's reminiscences has just been published.Students of Nazism and the war won't learn anything new here but Junge's testament as a witness to Hitler in his headquarters is a valuable insight.9/10.

Michael DeZubiria

Traudl Junge, one of Hitler's personal secretaries, finally decides to come out and tell the story of working for Hitler during one of the most catastrophic and studied times in German history. You sort of have to get past the fact that the movie is literally nothing more than a camera pointed at her while she tells these stories, it's certainly not what I had expected when I rented the film, but with subject matter like this it really doesn't matter. In a sense, if they had dramatized her story with photos, archive footage or, god forbid, reenactments, I think it would really have diluted the potency and immediacy of what she had to say. This is a woman who, at the time, was in her late teens and, like countless other people, she was intoxicated with the unnerving charm and determination and grand view for the future of the world. Yes, it's all told simply through the dialogue of this elderly woman talking to an interviewer, but this is a woman who met with Hitler face to face during his most powerful time, who watched him evolve from the dangerously charismatic leader with a master plan for the human race and into the darkly depressed visionary, fallen from power and overcome with defeat, faced with the crashing of his enormous ideals. She even tells the story literally of the last minutes of Hitler's life, during which he actually bid her farewell just before ending his own life. One of the things that really struck me was the amazing detail of Junge's memory. Here she is in her 80s, and she remembers word-for-word conversations that happened decades earlier, as well as remarkable details of situations and events. The looks on people's faces, who was where and at what time, as well as what was happening at those times, smells, emotions, sounds, etc. These are all of the things that good novelists use to convey a compelling sense of atmosphere which is, I think, one of the most important things to be created for a novel to be effective. I don't think at all that Junge's memory should be called into question, even though she remembers such striking details of things that happened so many years ago (and I don't think that her age should be a factor in deciding how accurate her memory is, either). This is a time in this woman's life that she has surely been going over and over in her head for decades, wondering how she could have been so fooled into thinking that she was working for a powerful, benevolent leader, and how she could not have seen what was really going on. She learns late in her life about a woman about her own who had been executed for opposing Hitler the same year that she herself came to work for him. It seems to me that a period in someone's life that has such a resonating effect of the rest of it is something that is remembered even more vividly than anything that happens later. The stories about Hitler himself are probably the most compelling element of the entire film. Junge tells stories about him that I would never have imagined, since like many people (to which this film is mainly aimed, I think) know little about Hitler beyond the public speeches that he made about his grand vision, where he displayed his amazing speaking abilities and his shockingly effective ability to make his vision, while always destructive to the people that he viewed as inferior, sound appealing to so many people. Obviously, a person would have to have some earth-shaking motivational speaking abilities to make people on a large scale accept and support something so murderous and destructive to humanity in general.

Some of the things about Hitler that I was most surprised by were things like his pet dog, Blondie, and his affection for her puppies, the way he is described as soft-spoken and polite when speaking to the young women working for him as his secretaries, the total transformation in appearance that he evidently underwent whenever he stepped before the cameras and microphones in public, the fact that he didn't ever want flowers kept in his office because he `hated dead things,' etc. Junge expresses her own shock at that last point, which surely mirrors that of anyone else watching the film. Can you imagine someone like Hitler, who engineered millions of human deaths, uncomfortable with flowers in his office because he hated dead things? It boggles the mind, and is also reflected by other revelations in the film such as his total detachment from everything that was going on in Germany as a result of his leadership. He even traveled in a train with the blinds drawn and was taxied through the streets to his destinations by drivers who would take the routes with the least amount of war damage so that he wouldn't be made uncomfortable. This is certainly not a traditional documentary, but the documentary genre is, I think, one of the most flexible genres in film. The subject matter is literally endless, and as this movie shows, even the simplest forms of the documentary can be enormously effective and moving. I think that the main purpose of a documentary is to provide information, not entertainment, and as long as it can do that I don't think that it really matters how intricate or complexly made the film itself is. Blind Spot provides plenty of information, and while the presentation is not exactly thrilling, it reminded me throughout of reading a book. One of the main reasons that I love to read (and, I think, also one of the reasons that people are so often disappointed with film adaptations of novels) is because it is always an individual experience. You create in your head the world that is described in the book, and film adaptations are someone else's vision of that world, which is pretty much invariably not the same as your own. This is why movies that are as closely faithful to the original material are so often the most critically and popularly successful ones. In Blind Spot, Junge tells her story in her own words without any kind of cinematic enhancement of them, allowing the viewer to create what it must have been like in his or her own head which, I think, makes the world and the events that she describes that much more vivid and immediate.

palmiro

Some people who have viewed and commented on this documentary have suggested that it is a sign of residual sympathy for Hitler (and maybe even for "National Socialism")if Hitler is portrayed in a human light: his "fatherly" qualities, his personal "warmth" and "charm," etc. But it is a great mistake to insist that, for Hitler to have been responsible for the monstrosities of the Nazi regime, he must have been a monster in his personal relationships as well. This leads to the facile equation: monstrous man commits monstrous deeds. And, of course, this proposition is very satisfying for most of us, because we think we can tell who's a monster and who is not in the political arena (everybody, that is, except for those dopey Germans of the 1930s). But the great lesson of the 20th century is that regimes can arise which do not require monstrous humans to do monstrous things--they do just fine with the human material available next door to all of us. Which is not to say that Hitler was not a psychopath or a sociopath, but only to say that he needn't have been one to be at the helm of a regime responsible for unspeakable atrocities. And so Frau Junge's portrait of Hitler should be seen as a reminder not to be taken in by the folksy, good-ol'-boy qualities of leaders, for whatever their personal likability may be, they can still be responsible for monstrous deeds.