filippaberry84

I think this is a new genre that they're all sort of working their way through it and haven't got all the kinks worked out yet but it's a genre that works for me.

Joanna Mccarty

Amazing worth wacthing. So good. Biased but well made with many good points.

Bob

This is one of the best movies I’ve seen in a very long time. You have to go and see this on the big screen.

Darin

One of the film's great tricks is that, for a time, you think it will go down a rabbit hole of unrealistic glorification.

bigverybadtom

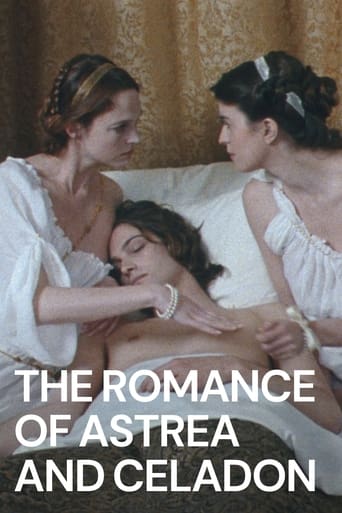

This movie is based on a 1610 French novel which takes place in fifth-century Gaul. The story is about the title lovers, children of two feuding families, and at a festival, Celadon tries to hide the romance by pretending to be in love with another girl. Though it was for show, Astrea assumes Celadon's infidelity was genuine and tells him she never wants to see him again, though he threatens to drown himself...and jumps into the river to do so.This causes distress to both the villagers, especially Astrea...but they are unaware that he had been rescued by three nymphs who take him to their castle. One nymph wants Celadon for himself, but another manages to smuggle him out and have him live in the forest, with her druid father coming to help him. But Celadon won't go home because Astrea ordered her not to see him. The rest of the movie revolves around getting Astrea and Celadon back together, which is much more time-consuming than it should be.The movie is full of elements that hardly evoke what fifth-century Gaul must have been like, including a castle and garden that must have dated from at least a millennium later, overly-refined statuary and writing and such, and the discussions of love and religion have little relevance to the overall story. Worst of all, however, is that the two lovers could have gotten back together without having had to resort to all the rigmarole-hence my review title.

oOgiandujaOo_and_Eddy_Merckx

I had a bad time with the last medieval-set film from Eric Rohmer, Perceval le Gallois, generally because it was shot on sets and I found Fabrice Luchini as Perceval incredibly annoying. Having an interest in the literature of the time I was uncomfortable with the portrayal.So I came to this one with misgivings, but fortunately it allowed some of the source material to breathe. The film is based on a 17th century novel called L'Astrée by Honoré d'Urfé. It is set in 5th Century France and is a romantic fantasy of the times. It seems that all characters are either shepherds, shepherdesses, nymphs or druids. I feel that Rohmer's style is quite inflexible, he shot this movie in squarish 4:3, as usual, whereas I felt the languor of the material, the playful Arcadian tone, the respect for the landscape (that Rohmer professes at the start of the film) required a more horizontal treatment of 2.35:1. Full-screen is what Rohmer typically uses and is good for his conversational films, or portraiture if you will. Here the material begs for something different, think for example of the British romantic painters William Etty and Lord Leighton, of Leighton's The Daphnephoria, Etty's The World Before The Flood, long sensual paintings. Rohmer does however try his best to find scenes that look best under 4:3, for example when Astrea takes her flock to high pasture up a steep meadow, there's no other way the scene should be filmed, it's more a case of Rohmer fitting the world to his aspect ratio though. I think that what works best for Rohmer in nearly all of his other films was a weakness here, the spartan conversational style.Celadon is a prince who has decided to live as a shepherd, having presciently followed Voltaire's advice that working the land is the key to happiness. He is loved by Astrea, a shepherdess. A tragic miscommunication between the two leads to their separation and peregrinations. Along the way we are treated to the usual Rohmerian banter about how love can't be forced, elective affinities, and the rationalisations and sophistries of love that each of the characters own. The main chat is between Hylas and Lycidas. Hylas is the equivalent of the bumble bee, he believes that men are meant to flit like bees from flower to flower, he is a joyful larger-than-life character. Lycidas on the other hand believes in monogamous love (with his beloved Phillis), a fusion of souls and both openly scorn the other, though Lycidas comes off as dour. I'm not convinced the philosophical material is a move forward from his earlier movies such as Pauline a la Plage, but it certainly is presented here with enough charm.The source material is well over 5000 pages long and obviously here we have a massive condensation. You can sense this quite often, for example when Celadon contemplates a painting of Psyche dripping hot wax on the sleeping Cupid. The painting is loaded with context, it's describing a scene from Apuleius' The Golden Ass, the only fully-surviving Latin novel, the whole episode is a rich and dense allegory regarding Platonism and different types of love, it's just skipped over here.The movie definitely is a pleasure to watch for me, despite the extravagance that the tale yearns to be told with, and which is barely present here. I don't think there is any director alive, or any budget that would see full justice done to the story, I think Rohmer succeeded as much as can be expected.

sandover

Raymond Radiguet concluded his novel "Count d' Orgel's Ball" in a masterly manner with the count's terrible phrase: And now, sleep, Mahaut, I want it so - mesmerizing his love into blackmail.What this has to do with Rohmer's pastoral romance? Its histrionics could not be more far than Rohmer's world. I take it as a perfect contrast to the film's end: young Astree cheerfully chirps to the exposed, from his previous cross-dressed role as a druid's sick daughter, Celadon: Vives! Vives! Je te le commande! which translates into something like: Live! Live! I order you so! This "into something like" has its own whimsical twist that makes me wonder about the extent of Rohmer's deliberate irony (and mine): Astree, or rather the actress portraying her, seems to me the more naive of the whole cast, and the more debatable on technical skills. I mean the troubadour, or rather a mockery of this, with his shrill voice, does not offend me as over-the-top in his performance, although he is a bit obvious. He is there for, in a way, us throwing darts to him. Perhaps Rohmer's mockery turned a bit harsh on him; one wonders if this was the case for Astree. It makes me think of Kubrick's sly choices of leading men in his films: the actors' public image as exemplary cases of somewhat ridiculous virility, in Kubrick's hands turned into the films' advantage.Of course this sadistic strain does not occur in Rohmer, far from it. So, why do I mention this? Here comes the punchline: because Astree's articulation is so blurred, her acting so bad and fresh, that the first time I heard the film's final sentence I thought, astonished and confused, that she was saying "Je telecommande!" that is, literally, "I TV order".Was this Rohmer's last word? For even if I cannot argue that wordplay is something he pursued in his films (although the early short "The Monceau bakery girl" features the amorous homonymy "ca me dit/samedi" in the flirting exchange "Ca vous dit?" "Oui, ca me dit." "Sortons donc Samedi." which means "It sounds okay?" "Yes, it sounds okay." "So let's go out on Saturday."), I cannot claim either that this was something he overlooked. The film in its simplicity, exemplifies an amazing level of sophistication. For to achieve such illusory simplicity, that also dares to play with our allusions of a soft-porn sensibility, or mock-philosophy (listen how the druid's discourse on trinity has the volume turned down a little, as a soft pedal occurred), well, it warrants a master's touch.I am left amused, or rather bemused, than perplexed. It is as if this doesn't actually matter, and one wouldn't want it otherwise, mesmerized away from TV, into somewhat more difficult pleasures posing as, and with pastoral simplicity; it all is spiritually uplifting.I will soon revisit - and live! - this little quick-silvery film.

Chris Knipp

Eighty-seven now, the indefatigable Rohmer still explores his obsession with young lovers. In this his declared swan song, he follows the theme via the pastoral romance of Honoré d'Urfé, penned in seventeenth-century France and set in the Forez plain in fifth-century Gaul. This is a classic star-crossed lovers tale with a happy ending that involves some cross-dressing by the pretty Celadon (Andy Gillet). He thinks his girlfriend Astrea (Stephanie Crayencour) has forbidden him to come into her sight, so he poses as the daughter of a high-born Druid priest. Though too tall, as cross-dressers often are, the striking Gillet is certainly beautiful enough to pose as a girl (Crayencour, though appealing, can hardly compete for looks—till she bares a breast, one area where Andy can't compete). When Celadon, as a "she," gets so friendly with Astrea they start kissing passionately early one morning in front of some other girls, there's some titillating gender-bending going on that gives this otherwise odd and dry piece some contemporary interest.As opening texts explain, the film was made in another region because the Forez plain is "urbanized" and otherwise ruined today. The mostly young cast wears costumes designed to evoke the seventeenth-century conception of what d'Urfe's antique (and largely mythical) shepherds and priests wore. Just as Rohmer's contemporary young lovers in his "Moral Tales" have little to distract them from their flirtations and love-debates, d'Urfé's characters are those of an ancient pastoral tradition who never get their hands dirty and spend their times in quiet, paintable pursuits like dancing, singing, or frolicking in the grass discussing the ideals of courtly love. Rohmer uses this idealized world as a more detached version of his usual emotional landscape. However, this film is more similar to the artificial and somehow un-Rohmer-esquire late efforts 'The Lady and the Duke' and 'Triple Agent' than to his really charming and characteristic work.In the beginning of the story, the lovers have apparently had a spat. Celadon allows Astrea to see him dancing and flirting with another girl at a dance. Later he insists it was only a "pretense," but Astrea jumps to the conclusion her boyfriend is a philanderer and is so angry she banishes him forever from her sight. His reaction is to throw himself into the river. While Astrea and her girlfriends go looking, he's washed up on shore at some distance, nearly drowned. He's rescued and nurtured back to waking health by an upper-class nymph (Veronique Reymond) who lives in a (presumably seventeenth-century) castle.A druid priest (Serge Renko) and his niece Leonide (Cecile Cassel) supervise Celadon after he flees from the nymph's clutches. He pouts in a kind of pastoral tepee for a while, and then is persuaded to put on women's clothes so he can be close to his beloved. One wonders if Rohmer hadn't lost control of the casting when we see the over-acting, annoying Rodolphe Pauly as Hylas, a troubadour who opposes the prevailing platonic tradition in favor of free love with multiple partners. Pauly completely breaks the heightened, elegant tone and introduces an amateurish note, which is the more dangerous since the simplicity of the outdoor shooting already risks evoking some French YouTube skit. Things liven up considerably when Celadon is in drag, but by that time Rohmer will have lost the sympathy of many viewers.Adapting seventeenth-century pastoral tales to the screen may be a far-fetched enterprise at best, but there must be better methods than this. Paradoxically, though the pastoral ideal is about purity and simplicity, recapturing it is likely to require more elaborate methods than this. The Sofia Coppola of 'Marie Antoinette' might have managed it—and that film does have a pastoral interlude, though not "pure" pastoral but aristocrats camping it up as shepherds and shepherdesses. Rohmer's bare-bones methods worked well for most of his career because the people and their conversations were interesting enough in themselves; the intensity of his own interest made them so. Such methods don't work so well here. The talk in 'The Romance of Astrea and Celadon' is too stilted and dry most of the way to hold much interest. For dyed-in-the-wool Rohmer fans, of course, this mature work is nonetheless required viewing. Newcomers as usual had best go back to 'My Night at Maude's' and 'Claire's Knee' to understand the perennial interest of this quintessentially French filmmaker.