Geraldine

The story, direction, characters, and writing/dialogue is akin to taking a tranquilizer shot to the neck, but everything else was so well done.

dromasca

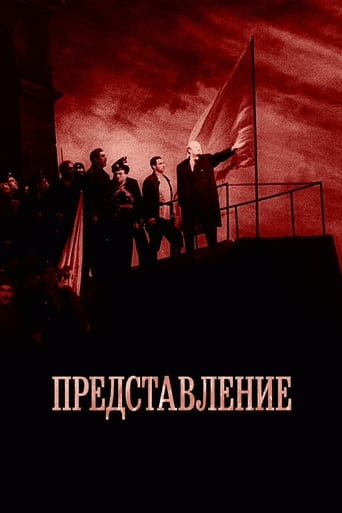

Nostalgia seems to be at fashion in Eastern Europe and maybe in Russia more than any other place. This collection of documentary clips from newsreels and documentary films of the 50s and 60s Soviet Union may be an opportunity to feed such feelings, and may be as well a window open to the reality of a time which slides back in history while continuing to influence the lives and reality of today.One just needs to pay attention because the window is almost never open to the reality as it was, but rather presents life in the perspective deformed by propaganda and painted in the rosy colors and accompanied by triumphal music and the wooden language commentary of the time. Sure, there are some glimpses to the real lives of people, and these lives were not only grim, people coped with the situations, they learned, singed, worked, loved and many of them never knew anything else but communism and believed in the system. Yet, in the perspective of history some of the tragedies of the time make their place even beyond the smoke curtain of propaganda: a public process for a pair of retired people condemned for the crime of feeding their pig with bread (like there was anything else to feed animals with during these times) or an innocent report about the valiant actions of a local policeman in a place named Katyn. You just need to pay attention.Another visible aspect is the cinematographic mastership of the makers of the epoch films. Excellent cinematography, beautiful takes, small pieces of art or poignant documentary sequences surface all the time reminding us that the Soviet cinema school was one of the best of the time, and one of the best in the history of the seventh art.The choice made by director Sergei Loznitsa of not making any commentary is excellent in my opinion. Such strong images speak by themselves. They speak when they show reality, even if this reality was deformed or prefabricated for propaganda purposes. When watching people you seldom have the feeling that they are speaking truth. If fans of nostalgia should focus on something it should be maybe the faces and language of people. Then they should ask themselves if there is really that much to be nostalgic about.

chuck-526

I watched "Revue" at my local theater's "screening room". All the black-and-white archival footage of the old USSR was fun to see. I saw firsthand seas of Young Pioneer scarves, lots of tractors and other farm equipment, flooded residential areas, large apartment blocks, reinforced concrete and modular construction techniques, huge factory chimneys belching smoke, a great emphasis on manufacturing steel, exercises in "taming" nature, and much more.You can learn more looking at these pictures in a couple of hours than you would spending hours reading lots of political and social histories; "Revue" substantiates that old trope "a picture is worth a thousand words". These clips are selected, edited, and sequenced; so you spend a short enjoyable time absorbing some history without being subject to that dusty patina of a professional historian exploring every scrap of archive footage. The hands of the original photographer and of the film composer are predictable and not ponderous, opening the possibility of gleaning a first hand view of life in the old USSR.The emphasis on manufacturing steel was reminiscent of things I've heard about Mao's China. These events were before the "age of OSHA". Efforts to tame nature didn't appear entirely successful even at the time, and were consistent with my impressions of environmental catastrophe across the USSR decades later. All that mechanized equipment must have used an awful lot of oil. And the out-sized farm equipment -which would have dwarfed anything except large collective farms- seemed to be new (almost unfamiliar) to the farmers. Given how much equipment (boats, rafts, floating walkways, etc.) was readily at hand and how the people went on with their daily routines, the flood must have recurred in most years.There's no "narrator" nor "voice over", so whatever points the filmmaker wants to make either have to be very unsubtle or have to be repeated many times. One unsubtle comparison was of "new" and "old" ways of germinating seed. The "new" method used the trappings of a scientific laboratory: notebooks, white coats, standardized glassware, measured ingredients, and so forth. The "old" method was nothing more than wrapping up the seed and burying it in the snow in the side yard. Clearly the "old" method got equal or better results for a lot less effort. Lots of sequences seemed to poke fun at "superfluous bureaucracy", but it's not clear to me whether this is symptomatic of the just the old USSR or of governments more generally in that period.The construction techniques with reinforced concrete and modular construction led to apartments with small rooms and concrete walls. To enable each module to be separately picked up by a crane, every module had to be very sturdy; each module was small, included all four walls, and had only little window openings. The result was those "heavy" and "repetetive" buildings that we denigrate as "Soviet Architecture". The style that had previously been a mystery to me suddenly not only made sense but seemed inevitable.There were bits of "inspirational" art (including what we might now call the "heroic worker"). Statues and mannequins of Lenin (and some of Marx) were ubiquitous. Those displays were so obviously "propaganda", I couldn't see them as "art" even though they may have been intended that way. Some of it seemed to me very similar to the US government's efforts to garner support for WWII, such as those "Uncle Sam Wants YOU" posters, or cartoons showing Hitler as the big bad wolf and the little pig's brick house sprouting huge cannons. And having just looked through a collection of posters, pamphlets, and photographs from the depression-era CCC (Civilian Conservation Corp) in the US, the "heroic steel worker" seemed less like the product of a warped imagination and more like a copy of the US a decade earlier.All those tractors, seed drills, ice drills, caterpillars, steel mills, refineries, earth movers, and so forth seemed to be based on technologies that sprang fully formed from something other than local roots. It was obvious they hadn't grown up from anything that was there before. These pictures supported claims that much of the USSR used technology imported from the US.Many of the performance sequences were of simple singing and dancing. Maybe I was supposed to see them as insipid and overly political, but I didn't see them that way at all. Rather, I saw them in the context of the recent Uighur unrest in the Xinjiang region of China. (China's social policies regarding ethnic minorities were simply copied from the USSR a long time ago.) I saw most of the performance sequences as attempts to base art on folk traditions, preserving and building on what was there previously. These sequences weren't a whole lot different than the photos in the old "Soviet Life" magazine. Some were pathetic and precious, but that seemed related to social policy rather than political organization. And looking closely at the faces -especially in the chorus sequences- a few stood out as being very different from the rest. These must have been children of "native" ethnic groups that had chosen to assimilate as much as possible. The old USSR policy regarding ethnic minorities was definitely more enlightened than similar policies in the West at the time. I couldn't though judge from "Revue" whether or not the policy actually worked all that well even back then, because I could only see the positive exceptions. I guessed in any case the policy wouldn't have kept working in the USSR fifty years later ...but the update was superseded by other events.