Cleveronix

A different way of telling a story

Tobias Burrows

It's easily one of the freshest, sharpest and most enjoyable films of this year.

Quiet Muffin

This movie tries so hard to be funny, yet it falls flat every time. Just another example of recycled ideas repackaged with women in an attempt to appeal to a certain audience.

Jakoba

True to its essence, the characters remain on the same line and manage to entertain the viewer, each highlighting their own distinctive qualities or touches.

Jackson Booth-Millard

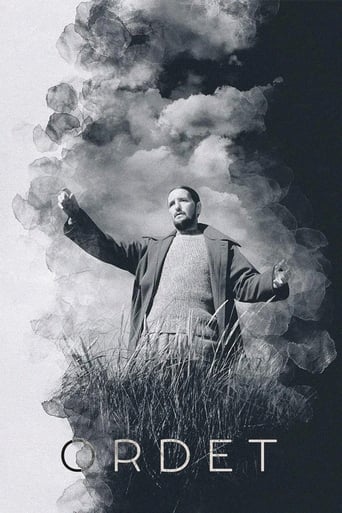

From director Carl Theodor Dreyer (The Passion of Joan of Arc, Vampyr), this Danish film featured in the 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die book, and besides knowing the director that was good enough reason for me to see it. Basically this film is a good representation of questions we ask about faith, such as what we believe, whether or not to believe, the reasons and needs for prayers, and our ideas of what miracles are. It is August 1925 in Denmark, where on a farm Patriarch Morten Borgen (Henrik Malberg) has three sons in different situations, good-hearted agnostic Mikkel (Emil Hass Christensen) whose wife Inger, Mikkel's Wife (Birgitte Federspiel) is pregnant, Johannes (Preben Lerdorff Rye) who is crazy or having a breakdown where he believes he is Jesus Christ, and young Anders (Cay Kristiansen) who is in love with and wants to marry Kirstin (Sylvia Eckhausen), the daughter of tailor Peter Petersen (Ejner Federspiel). Petersen objects to the idea of his daughter marrying a man who believes in Lutheranism, i.e. the freedom of black people as protested by Martin Luther King, but Borgen is demanding it because of his pride taking over. Inger has problems during the pregnancy, and a Doctor (Henry Skjær) is brought in to help her and ease the pain, and the night sees all four different views of faith come in to play, including Johannes who claims, as Jesus, that he can heal her, or that when she dies she will resurrect, like the true Holy son did. Of course tragedy does strike when Inger does indeed die from the pain during the labour, and there is a funeral with an open coffin, and it is there that Johannes does ask God to raise her from the dead, and the miracle does occur, with Morten and Petersen rejoicing that she alive, Mikkel regaining his faith and understanding the stillborn son is with the Lord. Also starring Ann Elisabeth Groth as Maren Borgen - Mikkel's Daughter and Susanne Rud as Lilleinger Borgen - Mikkel's Daughter. The acting by many of the players is very good, I personally and particularly liked Lerdorff Rye as the son believing he is Jesus, the story has some very interesting scenes questioning sanity, and it really establishes that religion plays a big part of lives in the world for all sorts of reasons, it is a terrific religious drama. It won the Golden Globe for Best Foreign Film. Very good!

jacksflicks

***I see a couple of idiots don't like the review. Maybe it's because I misspelled Kierkergaard (corrected). Or maybe they just don't like what they can't comprehend.***I love Pauline Kael. As a film critic, she was the greatest. About Ordet, she said:"Some of us may find it difficult to accept the holy-madman protagonist (driven insane by too close study of Kierkegaard!), and even more difficult to accept Dreyer's use of the protagonist's home as a stage for numerous entrances and exits, and altogether impossible to get involved in the factionalist strife between bright, happy Christianity and dark, gloomy Christianity -- represented as they are by people sitting around drinking vast quantities of coffee."Yes, you could read it that way, if you were a cynic. But that begs the question of the film. (Anyway, they weren't drinking that much coffee.)The question for the current audience was the same for the audience of Kaj Munk's time: Are you going to "face reality" -- the reality of the New Order of the Nazis, or in Dreyer's 1955, the reality of materialism -- or are you going to reach beyond yourself, despite all the evidence, embracing even folly? (Erasmus was asking this centuries ago.)The lesson of Dreyer was the lesson of Kierkegaard. Whether your world view is bright or gloomy, stuff happens anyway. What matters is how you confront it, with faith or despair. I think Munk's and Dreyer's challenge still confronts us in the 21st century.As for Dreyer's success in getting the message across, at first I braced myself for a dour lecture. But I was surprised to find uplifting characters and even humor. Like all Dreyer's films, Ordet is mannered and stylized. But think of Eisenstein. Think of Bergman.Speaking of Bergman, I rather compare Ordet to The Virgin Spring. Both confront grief and end with a miracle.

federovsky

Time for my annual dose of Dreyer, taken like medicine. Is it fair that Dreyer has a reputation of being turgid, slow, archaic, depressing, theatrical? Well, yes. Look at this. A large part of the time is spent watching people walk slowly from one side of the room to the other. In fact, this seems to be Dreyer's main directorial idea because the rest of the time they just stand there like hatstands. At climactic moments a door may be opened. There is no attempt to vary pace or tone; the dialogue is as stilted as silent movie cards. In fact, this looked and felt like a film made in 1915, not 1955.The film presents a Danish society so insular that subtle shades of Christianity tear them apart. That might be interesting if treated with any sort of subtlety or depth. Not here, where the plot is built with a few huge stone bricks. And we have not one but two of the most morose characters in all cinema. Old Borgen, who has the lion's share of the dialogue, always stares fixedly into the middle-distance while speaking - I presumed he was reading his lines off a card.Dreyer is a man entirely without humour. The mad son Johannes looks like Rasputin with slicked down hair and an immaculate centre-parting; he thinks he is Christ and walks in and out slowly spouting religious twaddle in a high pitched monotone with no facial movement whatsoever. Perhaps Dreyer was paying homage to Ed Wood here. Johannes' every appearance is unintentionally hilarious. If he can't see this, Dreyer really must have something missing. If you're not laughing at Johannes yourself every time he appears, I'm not sure I want to know you.And never have I been so let down by the ending of a film. A literal deus ex machina that I simply found intellectually offensive - all the more so because we can see it coming a long way back but are still led at snail's pace towards it.Painfully sincere, and good for the soul maybe, but woefully unaccomplished. To be enjoyed only by Quakers.

Cosmoeticadotcom

Denmark's Carl Theodor Dreyer was one of the great auteurs of early cinema, and such masterpieces as Vampyr and Day Of Wrath attest to that fact. Many critics, however, have hailed either his earlier silent film, The Passion Of Joan Of Arc, or his later Ordet (The Word) as his greatest work, and while I've never seen the earlier film in a full restoration, having just watched Ordet I can say, uncategorically, that it is not in a league with Vampyr nor Day Of Wrath. This is not to say that the film is a bad one, but it is nowhere near a great one…. Ordet is not even a direct allegory on evil and complicity with it, as was the earlier Day Of Wrath, made during the occupation. In fact, it is not really an allegory at all, merely a simple tale of faith, and a none too original one, at that. Its ending is telegraphed all throughout the film. Its ultimate message, about the power of faith over strict rationality, is also not a new one, and its rendering here is not in the least powerful. Compared to, say, Ingmar Bergman's Winter Light, made only a few years later, this film pales in every measure of comparison. That later film was loaded with vitality, even as it was a despairing film. Despite this film's seemingly upbeat ending (resurrection is a good thing, right?), it has none of the verve nor power Bergman's film has. Its characters never resonate with the viewer the way Bergman's tormented pastor and his scorned lover do, in their anomic faith and intellect, and their probing of it. Nor were Munk nor Dreyer the writers that Bergman is. And, compared to Day Of Wrath's ending, wherein that film's female protagonist's descent, into the insanity of feeling she has become a witch, haunts a viewer with regret, the resurrection of Inger seems too pat an ending, and not too challenging in terms of religion, nor science. To answer, though, that this is because this film is about faith and its necessity doubt, as framed by Kierkegaard, therefore one must suspend disbelief to 'get it', is to let Dreyer's own filmic and writing failures off the hook because those things he was in control of also fail, despite or because of that belief system. I'm sure that there are many critics who have been, and are, more than willing to grant the director such favor, as I read enough of them in my researching the critical reception this film got, but you'll have to look elsewhere for such poor critique. If the Internet bores you, try the books of Leonard Maltin or Roger Ebert. I'll be rewatching Vampyr in the meantime. I need its fillip after Ordet.