Matrixston

Wow! Such a good movie.

Softwing

Most undeservingly overhyped movie of all time??

Dirtylogy

It's funny, it's tense, it features two great performances from two actors and the director expertly creates a web of odd tension where you actually don't know what is happening for the majority of the run time.

Bergorks

If you like to be scared, if you like to laugh, and if you like to learn a thing or two at the movies, this absolutely cannot be missed.

De_Sam

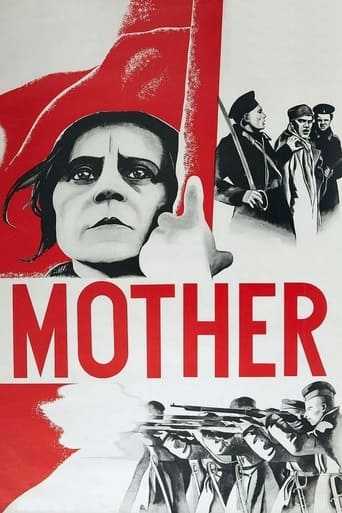

Максим Горький (Maxim Gorky), the novel author, has a direct link with the origin of cinema, as he was one of the first to write about it; on the 22th of June in 1896 Gorky witnessed one of the earliest film productions of the Lumière brothers, an experience that would be the basis for 'in the realm of shadows'.Gorky was impressed by film's potential to be an universal language, the ability which Мать (Mother) illustrates by adapting his written work to the screen so even the illiterate Russian people could understand his story.Всеволод Пудовкин (Vsevolod Pudovkin)'s style is more akin to the social realism (although this is influenced by the fact that the novel can be categorised as social realism) that Stalin would prefer, in contrast to the more abstract and jarring montage of Сергей Эйзенштейн (Sergei Eisenstein). A particular form of montage that he used in this film is worth mentioning, namely the fragmentation of action. Pudovkin 'cuts' the action into several different shots that only show a part or fragment of the action, when assembled in a montage the viewer's mind fills in the blanks (cf. Gestalt psychology) to create the illusion of a complete action. The most known example of this technique in Film is probably the shower scene from Psycho. This in itself proves the impact the Russian film school has had on film practices in general.To conclude, Мать (Mother) is historically important and on some parts technologically innovative. However, if it seen on itself and in comparison to other works of the time, for me it does not hold up as well as most film theorists and critics would have you believe.

Phobon Nika

What is it, where is it, how will it affect me? The following of one woman's struggle against Tsarist rule during the Russian Revolution of 1905. Мать, the pristine and devastating silent early work of the bustling mid-1920s Soviet Propaganda film industry, is a triumph on many levels. The ethos surrounding films like it of that certain age and origin: Eisenstein and his similar other Godly directors, is heavily scholarly, intellectual and time-dedicated, so to analyse Мать inside out really is well and truly beyond the amateur's concern to be a condescending writer. But, to be realistic, it's a naïve disgrace to formality if a list doesn't feature one of them on it. Vsevolod Pudovkin, a less known director of the decade's masterminds yet still heralded as a legend by his cult following for his innovative and often deeply personal practice, directs my personal, instinctive pick. Voted by an international panel of critics at the Brussel's World Fair as the 6th greatest film made up until the fateful judging day in 1958, it often loses limelight to the likes of Eisenstein's courageous, raw, untamed Battleship Potemkin and Dovzhenko's calmer, traditionally beautiful social study Earth. Мать, of course in its silent wisdom, force-feeds a supremely strong and vivid depiction of an individual struggle in a time of social instability. Whereas most works of the 1920s Soviet silent era focus on crowd mentality: whereby the struggle is depicted more of a Bayeux Tapestry of confusion and oppression, Pudovkin's take is lovely to see, and from the first few bold moments of Мать, we are introduced to our refreshingly small circle of main characters: a father, a mother, and a son. Few members of the audience will fail to identify with one person in such a configuration, as the aged camera-work of Мать still, after the prestigious test of time, provides a frame, a view to look in at each of the unique yet interconnected struggles of each family member. Мать evolves as clear as crystal before the eyes of any human of any outlook, a living and breathing piece of powerful, political art into a devastating slow riot for a new zero nation. As the realistic violence and suppression of the down-trodden progresses, a timeless and formulaic asset of the kind of film Мать must somewhat conform to be, there's something that smells a bit different in the air. We're always reminded of the maternal bond, its strength and power to drive a soul to unbearable torment, and how such a regime that these films fabricate propaganda against can directly sever it. This link that Мать explores is so volatile and hard-hitting to the blissful maximum extent that the limited medium of the silent, the black and white and that, again, time- honoured formula of the day can allow it to. Pudovkin's abilities with his 1926 sublime masterpiece generate an overwhelming empathy, giving the audience the completely, totally exclusive opportunity to visualise a fresh revolution through the eyes of those who are the most fragile and at risk emotionally from it.

Will E

Pudovkin's Mother is a strong film that refused to be bound by the limitations of its time and should remain interesting to contemporary audiences. The plot of the film is simply outstanding. While some would say it was to be expected since the film is based off of a novel by Maxim Gorky, it should be noted that good source material does not guarantee cinematic success. The film follows a mother and her revolutionist son, Pavel, as they navigate a series of difficulties resulting from her son's allegiance.With no speech, a major challenge for silent films is the creation of multidimensional characters. Pudovkin overcomes this challenge by being able to capture the emotions of the characters. I thought the mother, was exceptionally interesting. Her struggle did not only represent that of a loving mother, but also that of a movement. Pudovkin make great use of the camera, whether it was a side profile emphasizing the pensiveness of the character or a well-timed frontal close-up, he facilitates our ride on this emotional roller-coaster.For the most part, I really enjoyed the pacing of the film. While the pacing did vary in tempo, it was always well within its own "groove." Even in the extremely exciting conclusion, one did not get to feel the extremely fast-paced tempo of a Battleship Potemkin, which I believe speaks to the differences between the directors. On that note, it was interesting to see how Pudovkin's use of montage differed. His cuts were far more gradual and subtle when compared to Eisenstein's in Battleship which contributed to the stability of the film.All in all, Mother was a good watch and one of the stronger films that we have seen.

chaos-rampant

Structures shaping into motion, motions reshaping into structure, against each other, so that the whole thing is like a snowstorm rolling down a hill; gathering itself to itself. Which is to say the people to the people, in an effort at once to reshape and portray the reshaped world.Look here. The first third ends with a murder, so the entire part is about wild kinetic energy building to it; disenchanted workers plotting a strike – the metaphor for revolution, as so often in these films – factory cronies plotting to break them, pitting rugged father against idealist son. Meanwhile the factory owners, disinterested, arrogant, oversee the bloody drama from their lofty window.The second third ends with injustice, and so the entire second part is about the mockery of justice; a colonel promising the hapless mother her son – the instigator of events - will be okay if she surrenders a hidden stash of guns, then arresting him, followed by a mock trial where each of the judges presiding is a parody of human values.The final part is about revolution, so the entire thing is about the preparations of the final stand. Again the revolutionary metaphor, so poignant in these films; a prison filled entirely with workers, farmers, the oppressed with a dream languishing somewhere. And so, everything becomes imbued with meaning; the prison walls as walls at large, the doors slammed open with conflict, the bridge where passage is presaged by a rite of violence.The strikers scattered by mounted police into a mob, it's the mother who picks up the banner of revolution. Down by the bridge, floating ice is shattered on the concrete pillars; ice dissolves, floating away, but the bridge stands.And so the suffering and sacrifice of the nameless heroes is transformed into structures that will stand the test of time; bridges, factories, where the banner of revolution unfurls at the top, enduring symbols of a thriving industry, a healthy, self-sufficient nation. We may think what we want about the equation in terms of politics, but how it's equated through cinema? It comes with the natural ease that only a filmmaking tradition so deeply centered in its worldview could afford; the individual is transmuted, engulfed into a collective structure - the Soviet god in place of a god - , in a way that reveals the individual struggle to have been redolent with purpose all along. It's a spiritual vision, make no mistake; about communion with the life-destroying, life-renewing source; about harmony of structure from the chaos of forms.