Inadvands

Boring, over-political, tech fuzed mess

Matrixiole

Simple and well acted, it has tension enough to knot the stomach.

Hadrina

The movie's neither hopeful in contrived ways, nor hopeless in different contrived ways. Somehow it manages to be wonderful

Teddie Blake

The movie turns out to be a little better than the average. Starting from a romantic formula often seen in the cinema, it ends in the most predictable (and somewhat bland) way.

tedg

Sometimes you just find a gem. You're more likely to by following talent, and there's really not much of it. My following of Harold Pinter (as a writer, not as political observer) has never failed to reward. In a few years, we would have the amazingly layered "French Lieutenant's Woman." Pinter's interest is in multiple worlds creating — writing — each other and what it means to have art and life in such a context. An artful life.What we have here is richly inexplicable. It can be obviously threaded several different ways. One way is that Imogen Langrishe, one of three spinster sisters, has an affair with a visiting, "dirty scholar." It ends. If that's the most you can see, you might want to think about how your life is put together and what you are missing.Another, equally articulated thread is that we have three middle aged sisters. They are in a great house, once rich, but now near total loss. They are what remain of four daughters of a wealthy couple, one of which has apparently been elevated into a life imagined as bliss.Of the remaining three, Helen has created an imaginary lover. He is a German who is writing a thesis on notations in the Irish world (with reference to Goethe and the Brothers Grimm). She — in this story — keeps him in their cottage, splitting time between the house and his bed and table. Eventually, she writes herself out of this. It ends badly in some way and she retreats to bed, sulks and eventually dies of a broken heart.Helen creates this story and keeps it alive by literally writing it in the form of letters to her lover, never sent of course.Imogen (Imagine), another sister, is jealous. While Helen is out, Imogen reads these letters and decides to steal the man. So she creates her own imagined version of this man in the same cottage. Only he is dirtier, more vacuously pedantic, stiff, rude. She also ruts and strokes, takes possession. She does this under her sister's nose, with no attempt to hide.The sister watches in despair. We don't know why Helen's man left, but Imogen's version of him leaves because he gets better sex from the whore in the village. In effect, we are seeing Imogen's mind. She also spins and maintains this world and its affair by writing letters-never-sent, which — predictably — Helens finds, causing her death.In between these two threads is a rich melange of alternative threads and components vying for their own agency: the man writes the situation which places Imogen in her world, thinking she is writing it. What we have is an elaborate form of the Goethe "apprentice novel" where the hero encounters self as created in many worlds. Gothe claimed precedence in the Grimm parables.And inserted squarely in the adventure is Pinter himself, in a sequence involving a play which is about two characters on stage who we don't see, the two we do (Irons and Dench) and the two presented by Pinter and his one-eyed trollop. The four get drunk in a painter's flat (the artist outside the story — one of Pinter's devices), discuss the play devolving into four completely unconnected threads.Its rich stuff that doesn't advertise itself so, except in the title which only carries meaning when the play is seen as this multithreaded tapestry. And in a few otherwise inexplicable things planted so that the straightforward "interpretation" cannot be carried.Elsewhere I've been very critical of Dench, Dame Judi as she demands to be called. It seems to me that no matter what the requirements of the work she is in, no matter what she should do to fit in and support the artist intent, she blithely ignores its shape and does what she wants. Increasingly, these characters are all in the service of increasing the legacy of defining the woman Judy. Its the Kate Hepburn effect adopted by Angela Landsbury. If Dench were an artist, she'd let her art be her legacy instead of a managed personality.I just can't stand her any more. Perhaps the turning point for me was "Iris." But here — much earlier — she seems to take her responsibilities seriously. She knows what the thing is about and bends accordingly. Good for her. Irons does too. Good for us.Ted's Evaluation -- 3 of 3: Worth watching.

ayn5242

Yes, the acting was fine with every cast member turning in an honest and convincing performance. And there was plenty of atmosphere--the genteel poverty of the sisters, the rustic cottage of the scholar, the Dublin scene. But even Judy Dench and Jeremy Irons couldn't make it matter. The screenplay was so understated as to be incomprehensible. I never did figure out the business with the letters or the problem with the older sister. Dame Judy was quite a sexy number back in the day,and the young Jeremy was--as ever--terrifically appealing and gifted (although his nose looked a lot different than it did a few years later in Brideshead Revisited!). But as hard as they work to draw us in, we keep thinking, "Why?" Why are these characters doing what they're doing, and, most of all, why are we spending two hours of our lives watching a drama that is giving us back absolutely nothing?"

Rogue-32

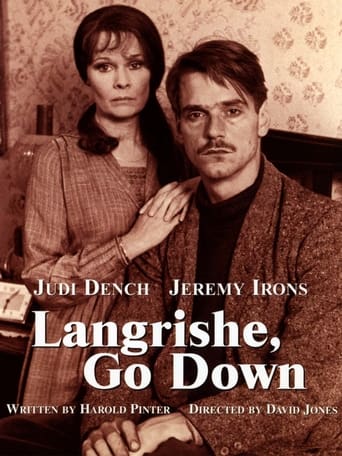

Pinter's "Langrishe, Go Down" is an exceptional piece of work, a beautifully written and multi-layered story as well as a masterful tour de force for its two leads, Jeremy Irons (brilliantly seedy as the 35-year-old leech of a 'scholar', Otto Beck) and Judi Dench, who brings the agonizingly conflicted Imogen Langrishe to life with superb subtlety. We realize their relationship is doomed from the start - partly because it's based on their two very different kinds of desperation - but in this piece, once the two of them have fully realized that the proverbial honeymoon is quite over, it's the WAY in which Imogen responds to Otto's casually-delivered, soul-crushing insults that gives the movie its ultimate power. If you get a chance to see this 16mm version of the BBC Play of The Week, do not miss it.

monabe

This telemovie from the 1970's deserves to be better known. Based on a novel by Aidan Higgins, it has a masterly script by Harold Pinter (who himself plays a small but significant acting role). If you enjoyed movies based on literature (such as James Joyce's wonderful story from "Dubliners" : "The Dead" directed by Huston) you should find this film well worth watching. A melancholy tale of frustrated love set in the 1930's features top acting performances from all. A young Jeremy Irons plays the German student of philosophy writing his precious thesis with excruciating preciousness and cynicism. (Irons slow pedantic accent is reminiscent of Marlon Brando's choice of accent for his "Burn".)He embarks on a relationship with a woman who is trapped by a family of sisters who - fallen on hard times since the death of the father- seem destined to live lives of slow desperation in their old house in the country. There are many wonderful scenes in this slow but engrossing production.