kckidjoseph-1

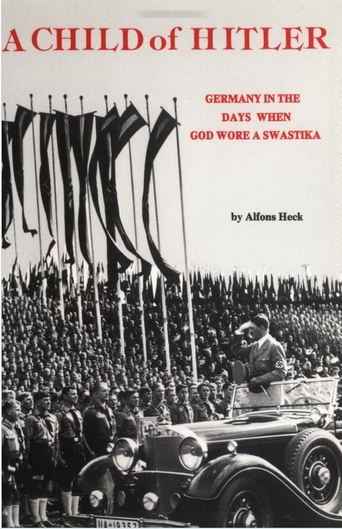

Alfons Heck, a small man with a shock of black hair, thick spectacles and a quiet, wispy voice, was not what one would expect an ex-Nazi to be. But then, what would a Nazi be? In retrospect, the Nazis' ranks were heavy with quiet little people who became inflated and intoxicated with power and went on to do bad things, the very worst, in fact, that humanity had to offer. When I met Heck in the late 1980s, he billed himself as the highest-ranking ex- Hitler Youth living in the United States. He had a bad heart, which had forced him years earlier to retire as a long-distance driver for Greyhound. He now went around the country with Helen Waterford, a survivor of Auschwitz, giving lectures on the dangers of Nazism and how such a thing might again happen, including in America. "Absolutely," he replied with uncharacteristic firmness when I asked if he thought Nazism or something like it could resurface in the U.S. Heck, who was born on Nov. 3, 1929, in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, wrote two books, "A Child of Hitler: Germany in the Days when God Wore a Swastika," and "The Burden of Hitler's Legacy." A 1991 HBO documentary based on his books, "Heil Hitler! Confessions of a Hitler Youth," used news footage and Heck's narration to explain how millions of youngsters were swept into what many regard as the most fanatic of Hitler's followers. Heck, who died in 2005 at age 76 of heart failure, freely admitted he was among the worst of the worst. He recently turned up on one cable documentary about the famous failed bomb attempt on Hitler's life, recalling that as a youngster "I was incensed. I felt that hanging was too good for the perpetrators." He uttered those words as he sat in Nuremberg, an especially meaningful place to Heck. By the time I met him, he claimed to have recanted, and I believed him, and still do. Yet it was sobering to listen to the path that he had followed. Raised by his grandparents in Wittlich, Germany, a small town on the border with Luxembourg, he was picked at age 10 to represent his school's Hitler Youth at the Nuremberg Party Congress. He rose quickly through the Hitler Youth ranks from 1939 to 1945, and became the youngest boy to reach the top ranking as a glider pilot in the organization's air wing. His goal was to join the feared German air force, the Luftwaffe, as a fighter pilot. At 16, with Germany's fortunes falling, he was put in charge of a small town on the Luxembourg border. At one point, he threatened to have an elderly teacher shot if he refused to let some Hitler Youth stay at a schoolhouse (the teacher relented and the order was rescinded). That year, Hitler gave Heck the Iron Cross for excellence of service. At war's end, Heck was captured by American troops, put on trial by the French occupying forces and sentenced to a month hard labor and restricted to his hometown for two years. He asked for and received permission to attend the war crimes trial in Nuremberg _ something that changed his views on the Nazis completely. After living in Canada for several years, where he met his wife and held a series of jobs, the couple moved to the U.S in 1963, settling in San Diego in 1970, where he worked driving a Greyhound bus. He had to retire in 1972 because of heart trouble. A period of depression followed, and his wife suggested he study writing and tell his experiences in a book. "A Child of Hitler" was published in 1985. He also wrote articles for San Diego newspapers, one of which was read by Holocaust survivor Waterford, who suggested they give joint lectures on Nazism. When I met Heck, it was a few short years since my mother and grandfather's death and learning that some of my own distant relatives had perished in the Holocaust. It was with mixed feelings that I accepted the assignment to meet with and profile him. I was prepared to hate him. That I liked him and believed what he had to say surprised me. A few weeks later, as I drove home one night and listened to him on a radio show hosted by a mutual friend, my name came up. "A very fine writer," he said in his wispy voice. It gave me chills. Had I fallen prey to the same Nazi charm and dictum that had drawn in Heck himself and so many others to disastrous effect? I believed not. I like to think human beings can change, even after making the most heinous of mistakes.