Dorathen

Better Late Then Never

Senteur

As somebody who had not heard any of this before, it became a curious phenomenon to sit and watch a film and slowly have the realities begin to click into place.

Catangro

After playing with our expectations, this turns out to be a very different sort of film.

Edwin

The storyline feels a little thin and moth-eaten in parts but this sequel is plenty of fun.

gavin6942

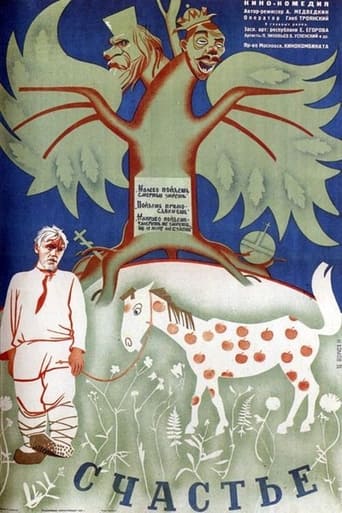

A hapless loser (with the surname of Loser) undergoes misadventures with avaricious clergy, a tired horse, and a walking granary (among other things) on his road to collectivized happiness.Unnoticed on its release, "Happiness" became well-known in the 1960s among film scholars. It was especially championed by Chris Marker who included some excerpts from "Happiness" in his 1992 documentary "The Last Bolshevik". I wish it had been noticed sooner and was better known today.Soviet film, at least in the early years, tends to be serious and quite political. Here it may be political, but it is anything but serious. There are some humorous moments mixed with some unusual camera tricks (watching food fly into the old man's mouth is a surreal experience).

chaos-rampant

Happiness as labor, sure enough. A farmer sent by his wife to find it, finds instead a wholly absurd Tsarist Russia where a saint in name would sooner drown than let go a bundle of rubles to the bottom of a river. But does he find it, you would think at long last, when a more subtly absurd Revolution sweeps the countryside? What a strange, uplifting joy to be able to see this silent Soviet comedy about a hapless schmuck caught in the wheels of a callous world. The filmmaker could have gone for a harmless Chaplin effect, assuming for a moment Stalin's censors stayed their hand, benevolent fates setting up pratfalls all the while taking care of life. The schmuck triumphs because he's pure inside, or a natural performer. But Chaplin was not honest with us. He was a hard worker, a staunch Marxist, but hard work is never a value in his films; no, he made his fortunes by selling people the Dream.The inspiration here is Buster Keaton, the stone face mute in the face of unfathomable mishap. Dogged effort.Let's unpack this a little. The wife is strong and resolute to the end, a hard worker, and it pays off for her. But this is not one of those amazingly farcical works dubbed socialist realist at the time and favored by Stalin, celebrating the flipside of that Dream as robust heroes of labor triumph in the fields in the name of the people. These fields are barren, dusty, crops are nowhere. Members of the commune are not all of them content worker bees, they are also cruel, weak, suspicious, human. Filthy brigands stalk the perimeters, the first true revolutionaries for Bakhunin let's not forget. The workers attack them with watermelons, the fruits of labor wasted on a squabble.But this is not simple criticism or direct confrontation with the regime, which sure enough would have earned Medvedkin a swift execution. Our gain is that this man was forced to find ways to dream further than the state-sponsored Dream had imagination to apprehend him.So what does he do? He envisions images with enough weight and shadow so that we fill the shape. He sketches dreamlike edges only. Anxious air. The man whipping his wife as she plows the field, otherwise they starve. A shaggy horse towing on its back a wooden cabin as it staggers to grab a meagre bite of hay. A grain storage room absconding on human feet. The man tasked to guard it mystified by the over-sized rifle he's given to guard it with. The same man later hidden in a chest and discovered by authorities by his sicle protruding from the chest.Make no mistake, the film is speaking about Soviet life in the fields. Its realism is the restless dream, the artifice, the world a size it doesn't fit the people.Curiously enough, it got past the censors but was mostly panned by the press. His next film didn't, a major loss for us. Soon after, he was rebuked by Party sycophants for daring to speak in favor of Eisenstein's Bezhin Meadow, then in production and soon to be likewise axed and destroyed. By then, the late 30's, it was all over for everyone, the film trains permanently derailed. On the other side, Buster Keaton had missed his own place in a revolution and was on his way to become a weary, beaten old man like the protagonist here. See if you can find Chris Marker's Last Bolshevik, a documentary where Medvedkin in his old age reminisces on all this.

MartinHafer

This is a propaganda comedy from Aleksandr Medvedkin. It is an allegory of a poor peasant named Khmyr and it's a silent film. However, the lack of sound is not what will strike you when the film begins. What you'll notice is that the film looks like a live version of a cartoon--with ridiculously cartoony action, characters and story.It all begins with Khmyr and his wife bemoaning their lot in life. They are hungry and their farm is barren and awful. You assume this is meant to be pre-Revolution Russia. Rich neighbors, the military, thieves and the church all conspire to keep Khmyr miserable. Even when Khmyr discovers a wallet stuffed with money, he STILL is miserable because once his farm is successful, these forces all arrive to take everything. And the only thing that saves him and gives him happiness at the end is the miracle of collectivization. Then, suddenly, he has nice clothes and things to eat.While some of the film (particularly the first portion) is rather funny, the overriding message is pure propaganda--so much so that it's hard to take the film seriously. The people from the church are all evil as are the rich--all tenants of Stalinist communism. And, according to the film, a collective system is the only solution--though the answer, in reality, cost millions and millions of lives during the early years of Stalin's reign. But, these losses, according to what you'd gather in the film were those who had it coming--greedy farmers who were counter-revolutionaries. And, in the film, these folks are apprehended by the good farmers and punished.To me, the film is way too preachy to be much fun to watch other than as a curio or perhaps to be used by a history class to discuss Stalinist Russia or collectivization. While reasonably well made, it's message is put across with sledgehammer symbolism--very obvious and very heavy-handed.

zetes

I really love silent cinema of all types, and some of my very favorite films are silent (Voyage to the Moon, Battleship Potemkin, The Passion of Joan of Arc, Our Hospitality, Sherlock Jr., Safety Last, City Lights, Modern Times). Battleship Potemkin (and Sergei Eisenstein in general) got me interested in Soviet silent film, so I was excited to find this particular title, Happiness, on my local video shelf (although that is not a link, this is available for purchase, if not at Amazon, check other sites. I picked it up and put it in my VCR. I had expected something heavy and powerful like Potemkin (and many other films that I had read about), but it turned out not to be exactly what I expected. Happiness is, in fact, a Russian silent comedy. No, it is quite unlike the silent comedies of Keaton, Lloyd, and Chaplin. It shares a few characteristics (especially Chaplin's famed swift-kick-in-the-butt, so prevalent in his pre-feature-length shorts), but it is a lot more socially conscious. What's more, it manages to be both socially conscious (and very much so) AND quite humorous (also very much so). The main character, actually named Loser, is just a great character. He is the archetypical lovable loser. He can't do a thing right, ends up messing things up completely in every situation. At one point he is asked to protect his farming community's storage barn, and when trying to chase a goat away from some crops, he fails to notice a bunch of people literally steal the house!Perhaps the funniest scene in the film is the one where Loser chooses to give up his life (strange in comedy: there are two different scenes with jokes about suicide, and both actually work) because thieves stole his horse, the last bit of property he owned (though it was a particularly bad horse). He builds a coffin, measuring it for himself by stretching out in it to see if it will be comfortable. There is a great set piece where Loser is smoothing the wood of his coffin on a workhorse, and when he moves back and forth, shaving the wood, the workhorse moves rhythmically back and forth like a real horse (maybe you'd have to see it to understand). The local magistrate catches him doing this (i.e., planning suicide) and he speaks a very telling line: "If the peasants start killing themselves, where will we get crops?" "Killing yourself is illegal," the magistrate informs him. He gets the local wing of the army, in which the commons soldiers are no longer individuals, but rather automatons with big, puffy, rubber masks (they very much resemble the school children in the film Pink Floyd's the Wall). The captain of this troop, when Loser says that he can no longer live, says to his soldiers: "Beat him half to death!"The only problem with this film is that I believe some scenes are missing. The story is sort of difficult to follow at times. Otherwise, it is a very good film, unfortunately forgotten as so many old films are. 8/10