Aubrey Hackett

While it is a pity that the story wasn't told with more visual finesse, this is trivial compared to our real-world problems. It takes a good movie to put that into perspective.

Adeel Hail

Unshakable, witty and deeply felt, the film will be paying emotional dividends for a long, long time.

Sienna-Rose Mclaughlin

The movie really just wants to entertain people.

Matho

The biggest problem with this movie is it’s a little better than you think it might be, which somehow makes it worse. As in, it takes itself a bit too seriously, which makes most of the movie feel kind of dull.

Steffi_P

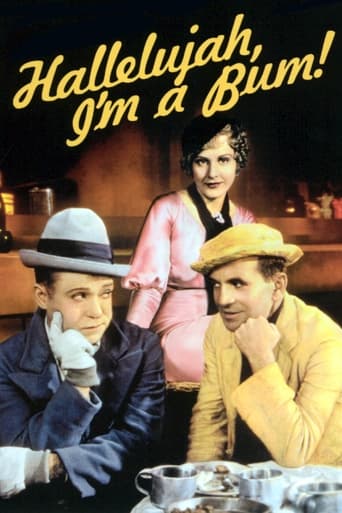

The story of the 1930s musical is very much the story of its stars. As the genre developed different stars came and went. And sometimes, established stars adapted alongside the musical itself. Al Jolson featured in some of the most successful movies of the early talkie era, in what were not really true musicals but stories about the music hall, essentially showcasing the persona Jolson had been playing for years on the stage. However by 1933 such theatrical musicals no longer cut it with audiences, and Hallelujah, I'm a Bum sees Jolson ditching his blackface and immaculate dinner suit for the battered attire of a down-and-outer in this topical depression-era musical in which the songs weave into the narrative.Hallelujah, I'm a Bum was not like those flimsily-plotted stage musicals, where the story really only existed to string the numbers together. Its screenplay is by no less a personage than S.N. Behrman, from a story by Ben Hecht. These two practically defined screen writing in classic-era Hollywood, and their list of credits is astounding. For this particular opus, they make light of the poverty-stricken times with a tale of homeless folk being cheerful about their situation. Rather disrespectful perhaps, but it's belittling poverty as much as it's ignoring the real unpleasantness of it. And all this jocularity builds into a very tender and poignant love story, giving a bittersweet twist without having to wallow in the depressing business going on in the streets at that time.The music and lyrics are by that celebrated duo Rodgers and Hart. Richard Rodgers is now of course better-known as having been one half of Rodgers and Hammerstein. His melodies are still just as beautiful, if a little less grand than they would be with Oscar Hammerstein, but Lorenz Hart was very much a writer of unique style, one that was crucial in the development of the genre. As oppose to the strictly stand-alone nature of most songs in musicals, Hart often leads in or out of a number with rhyming dialogue. He also has multiple singers take part in a song, often changing singer halfway through a line, making the song more a conversation than a performance. This all chimes in with the fact that the songs actually move the plot forward rather than commenting upon it.Director Lewis Milestone didn't too many musicals, but he was a great stylist as a filmmaker, using technique to build rhythms and tones on the screen. And this was ideal, because just as musicals were becoming less about stage performances, so too did they become more fluid in their stylisation. Milestone is great at making a choreography out of normal actions, such as Bumper and Acorn hitching a ride on the back of a cart on their way to New York. He makes every frame compliment the dynamics of the music at the time. In the first version of the title song, he switches quickly from a thronging crowd to a shot of Jolson on his own beside a tree, a couple of people walking leisurely in the background. It's a sublime moment.As for Jolson himself, he may have changed his clothes and surroundings, but he still has all the charm and appeal that made him the most popular entertainer of his day. At times his movements are so hammy they would look ridiculous from any lesser performer, but Jolson has such a genuine earnestness he makes us overlook that. When he makes his defence in the "trial" scene and does the little routine with two imaginary fleas, it harks right back to the music hall, but he makes it fit to this more contemporary character, pleading in a way that is comical but also endearing. A brief mention should also go to Jolson's co-star Harry Langdon, an old silent-era comic who made some truly appalling feature films in the previous decade. But as a supporting player with some kind of structure about him, he is not too bad, creating a jolly little character with some carefully-timed mannerisms. Even if Langdon wasn't a rival to Chaplin or Keaton, he was certainly a good comedy actor.The early sound era had been a testing time for the musical. The genre had been thrust to the forefront of the new medium, having had no time to develop (there were of course no silent-era musicals!). But Hallelujah, I'm a Bum is really everything a great screen musical should be, showing a dramatic shift in structure and tone but with a consistency of heart that a player like Al Jolson could bring – even if the demands upon him are slightly different. It demonstrates that, by this stage, the genre had well and truly arrived.

zetes

Delightful, offbeat musical starring Al Jolson. He plays the King of Central Park (basically king of the bums). He likes his carefree life, and is actually good friends with the real mayor of New York (Frank Morgan). One day, Morgan suspects his girlfriend (Madge Evans) of theft and basically kicks her to the curb. After a suicide attempt, Evans develops amnesia and becomes Jolson's girlfriend. Silent film star Harry Langdon appears as Jolson's communist friend. The Depression era politics are odd and interesting. I wonder if the film's weirdness is the reason it kind of flopped in 1933, and why it's so little known today. I can't say it's a great film - the story's not strong and it definitely fizzles in the end. And the Rodgers and Hart score isn't especially memorable (and the sound is so tinny the lyrics are pretty difficult to understand). But it's a must-see.

st-shot

This upbeat depression era musical features Broadway sensation Al Jolson as hobo king Bumper. Living in Central Park he and his followers choose a life of leisure to wage slavery debating it in song and rhyme with among others a Red grounds keeper. Even though he's a confidant of the mayor he prefers his laid back lifestyle to patronage work. One night Bumper saves a woman who throws herself off the Bow Bridge. Stricken with amnesia she takes up with Bumper who falls hard enough for her to get a job. When Bumper's "Angel" get's her memory back things change and Bumper returns to his previous vocation.By 1933 massive unemployment stretched across the land and I can only imagine what the audience reaction of the time might be regarding a musical that extols the joy of joblessness. Jolson's popularity was on the wane having been supplanted by Bing Crosby but he still had enough draw in his voice to make Hallalueh, I'm a Bum a moneymaker and the flimsy story written with sly subversiveness by Ben Hecht does have a light satiric humor to it.Edgar Conor as sidekick Acorn and silent film clowns Harry Langdon and Chester Conklin add to the film's amiability while Madge Evans as the amnesiac retains a sinewy seductiveness in an evening gown she wears for days on end. Director Lewis Milestone adds his usual camera movements with a striking tableaux here and there but there is also some sloppy back projection and pedestrian editing that gives the finished product a rushed feel. Overall though Hallalueh, I'm a Bum is an oddly interesting take on tough times featuring a legendary talent in fine form.

theowinthrop

I see this film and love it, but I also wish to cry a little.The image of Al Jolson, to this day, is the first star of sound movies who appeared in minstrel make-up. It has damaged his historical record in a way that is hard to question. While Jolson did show up in many scenes in his films without burnt cork on his face, his show stoppers were usually his "Mammy" numbers. So people will watch him in a few films (most notably THE JAZZ SINGER, ROSE OF WASHINGTON SQUARE, and STEPHEN FOSTER) but they will not watch films like WUNDERBAR or GO INTO YOUR DANCE. You'll notice that the films ROSE OF WASHINGTON SQUARE and STEPHEN FOSTER were late in his film career, when he was supporting Tyrone Power, Alice Faye, and Don Ameche, and (in the former) the main story concentrated on Faye, and the latter was a historical film (or claimed to be) set in a period when minstrels (Jolson's "Edwin Christy") were perfectly acceptable.HALLALUJAH, I'M A BUM is a notable musical for several reasons: Jolson is able to perform in a relatively relaxed mode as a hobo - the "Mayor of Central Park". He is also shown as egalitarian, traveling around with his friend Edgar Connors (who is an African-American). The film was one of a series of musicals done in Hollywood by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart (who appear in cameo parts in this film) where the dialog changes from regular speech into a singing speech the characters all join in on. This was done with George M. Cohan, Jimmy Durante, and Claudette Colbert in THE PHANTOM PRESIDENT the year before, and would reach its fruition in the film LOVE ME TONIGHT. The score is above average, with one real standard: "YOU ARE TOO BEAUTIFUL". It has a curious view on economics and happiness, due in part to the atmosphere of the Great Depression. And there are some nice side features: Frank Morgan as the Mayor of New York, Madge Evans as his girlfriend, and Harry Langdon in an odd part as a leftist part-time hobo who is also a street cleaner. Langdon (unpopular with the other hobos in general) is not the only silent film comic in the film. Chester Conklin plays a friendly carriage driver. Another hobo is played by W.C.Fields occasional performer Tammany Young.The film follows Jolson's "Bumper" on his winter vacation in the South and notes his close friendship with Morgan's Mayor. There are hints about a current scandal in New York City there: Morgan frequents the Central Park Casino with Evans for lunch and dinner. The Casino was frequented in the late 1920s and 1930s by then New York City Mayor Jimmy Walker and his girlfriend Betty Compton. Jolson stumbles onto a purse (Evans) that contains a $1,000.00 bill. He tries to return it, but Evans (after a quarrel with Morgan) has left her apartment. Subsequently Jolson does meet Evans when he rescues her in a suicide attempt that leaves her with amnesia. He falls for her, and decides to take a job to take care of her, and eventually marry her. In the meantime Morgan is troubled by Evans vanishing so totally, and starts drinking heavily. I won't go into the film's conclusion.The film shows that being a hobo means having unlimited freedom, and a lack a pressure from the cares of the world. Most of the talk-sing songs deal with the relative happiness of the hobos. Only Langdon shows the irony of the situation. He feels the world will only be set right when everyone has a job, and supports themselves. He sees a type of Communist happiness in the future. He also sees that the hobos, by cadging and living off working people and businesses (Jolson gets leftovers from the Casino) are as parasitic as the very rich. These views make Langdon unpopular generally with the hobos. Only Jolson really tolerates him at all.It is a unique musical for its time, and a welcome addition to Jolson's work. Certainly well worth viewing. But it still saddens me: if only Jolson could have made more films like this one.