AniInterview

Sorry, this movie sucks

Konterr

Brilliant and touching

HomeyTao

For having a relatively low budget, the film's style and overall art direction are immensely impressive.

Kinley

This movie feels like it was made purely to piss off people who want good shows

maurice yacowar

Joseph Cedar's Footnote (2011) is a very different film than his Beaufort (2007). It's an intimate family drama, often comic, without explicit political reference. Yet both warn audiences against the dangers of the bunker mentality. In the second, set on the home front, the leading characters suffer from the destructive intransigence of their wills. The central figures, the famous Talmudic scholars Eliezer Shkolnik and his son Uriel, and their archenemy Grossman are so firmly set in their righteousness that they cannot countenance the compromises that could lead to justice and to peace of mind.Indeed the film's key word is "fortress." Uriel publicly thanks his father for having made their home a cultural fortress. When Uriel secretly writes the jury's supposed citation for his father's mistaken award, he slips that term in again. That word prompts Eliezer to doubt the validity of his award — and enables him to remember that the cell-phone call informing him of the prize named his son, not him. Eliezer's hunger for the award deafened him to his son's name.The settings support that term. The offices, the library, and especially both scholars' homes are veritable fortresses of books and papers in their case dedicated to the abstruse minutiae of Talmudic studies. They live in a fortress against the realities and obligations outside. In this sense the film may allude to the problematic isolation of Israel's burgeoning Haredim community from the responsibilities of Israeli citizenship. But Uriel is an academic star. On Shavuot eve he pops up all over the city delivering six lectures. Where Eliezer wears yellow headphones to drown out the outside world — i.e., his family — Uriel has become a public intellectual, a celebrity, to his father's disdain. Although Eliezer's parents moved to Israel in 1932, and he was born there, he seems to personify the Old Jew, Uriel the New. Eliezer is a couch cartoffle, while Uriel plays a mean, very mean, game of squash. Eliezer is resigned to being the Victim, having lost the Israel Prize 20 years running. When Uriel is victimized — the theft of his clothing in the gym — he responds with bravado, exiting in a fencer's uniform, assuming the aristocratic bearing of the German/Austrian enemy. In contrast, Eliezer bristles when the security guard asks him to bare his wrists — he reads the blue entry bracelets as if they were tattooed numbers. As in Beaufort, the Israeli security guard's German shepherd evokes the concentration camps. As Eliezer approaches his own award ceremony at the end, he seems completely dissociated from the surreal business around him — costumed dancers, drummers, the paraphernalia of a televised awards show — especially the puffs of gas-like vapour as the winners approach the stage. Though he was spared the Nazi nightmare this Old Jew assumes its psychological scars and its indelible memories — and responds to every slight with aggressive belligerence. In Eliezer's survey the definitions of "fortress" range down from security and shield to trap. Both men are trapped by their shields against each other. But where Uriel annually nominates his father for the Israel Prize and fights to let him keep it after the mistaken announcement, Eliezer uses the newspaper interview to attack his more famous son's academic standing. The family visit to Fiddler on the Roof leaves Eliezer complacently humming "Tradition," while his son seethes in anger and his wife is pained by knowing of her husband's delusion. Eliezer obviously missed the play's thrust, which is the fiddler's delicate balance on the rooftop trying to modulate his Tradition to deal with the changing world. For Eliezer tradition remains an indomitable fortress.Uriel's meeting with the awards committee is the film's most resonant scene. It begins with telling comedy: the room is so small, so crammed with chairs and people, that any movement is a problem. The image of people jammed together in too small a space clearly indicates that whatever other themes and issues the film may examine, it is crucially about Israel — the sliver of land surrounded by the sea and the massive nations of antagonists bent upon driving the Jews into it. In a space so small there is no room for such heated and profoundly protracted differences. Yet in that small space the conflicts persist. The space filled with chairs is also filled with egos, with fortresses, the characters determined to defend their principles to the end. Uriel properly challenges Grossman on the amount of anger and violence caused by his intransigent defence of his Truth. In that jam no compromise is possible. But in the freer confines of Grossman's office/fortress, Uriel manages to draw out a painful and expensive resolution. The space theme spreads beyond that room. Eliezer and Uriel are academically jammed into a minuscule area of scholarship. Eliezer constantly makes himself an outsider, getting trapped outside his son's award ceremony, walking beside the family car, standing apart in family photos. Grossman is ramming together his garbage cans when he calls to Eliezer his unwelcome Mazel tov on Uriel's success. The film closes on the TV host's instruction to rise for Hatikvah, Israel's national anthem. That confirms that the film's family drama and the academic politics are but metaphors for the nation's predicament. We don't learn Eliezer's decision on accepting the award because we don't know which way Israel's vehemently divided patriotisms will go. We don't hear the anthem but we know its powerful sway. Perhaps the clash of too rigid and righteous fortresses, each with its own ardent truth, risks reducing the national project to a footnote. For more see www.yacowar.blogspot.com.

gradyharp

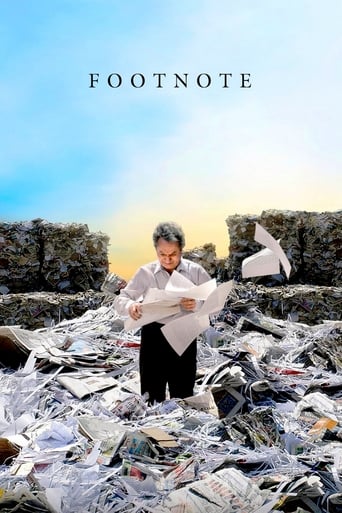

FOOTNOTE is an appropriately titled sparklingly intelligent and entertaining film written and directed by Joseph Cedar. With a small cast and a focused story this little film form Israel is not only a pleasure to watch as a story performed as shared by brilliant actors, but it is also one of the most visually artistic and creative venture of cinematography to be on the small screen in a long time: the genius cinematographer is Yaron Scharf. Add to this a musical score that enhances every moment of the story - courtesy of composer Amit Poznansky - and the film simply succeeds on every level.In a most ingenious way we are introduced to the two main characters - father and son, both professors in the Talmud department of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. The film opens on the confused and somewhat unattached facial expression of the seated father Eliezer Shkolnik (Shlomo Bar Aba) as he listens to his ebullient son Uriel Shkolnik (Lior Ashkenazi) being inducted into the prestigious Israeli academic union. Uriel's acceptance speech reflects his childhood when his father informed him upon questioning that he was a 'teacher' - an occupation the young Uriel found embarrassing at the time, but now honors his father for this guidance. After the ceremony we slowly discover that there is a long-standing rivalry between father and son. Uriel has an addictive dependency on the embrace and accolades that the establishment provides, while Eliezer is a stubborn purist with a fear and profound revulsion for what the establishment stands for, yet beneath his contempt lies a desperate thirst for some kind of recognition: his only clam to fame after long years of intensive research is that the man who published his findings mentions Eliezer in a footnote. When it comes times for the Israel Prize, Israel's most prestigious national award, to be awarded, a clerical error results in a telephone call informing Eliezer that he has won, while in reality the award was meant for his son Uriel. How this error is resolved open all manner of windows for examining family relationships, fame, pure academia, and forgiveness.The film is an unqualified success. Lior Ashkenazi (so well remembered from 'Walk on Water' and 'Late Marriage' among others) gives a bravura performance and that of Shlomo Ben Aba balances it in quality. The supporting cast is strong. Joseph Cedar has produced a fine film very much enhanced by the brilliance of the cinematography that tells the story as much as the dialogue. Grady Harp

Andres Salama

This bittersweet comedy from Israel is set in the rarefied world of academia and is a fine, interesting movie about the bitter relationship between a father and a son who both happen to be Talmudic scholars working at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and how their rivalry finally overcomes their filial obligations.Eliezer Shkolnik (a terrific performance by Shlomo Bar Aba) is the father, and he seems a personification of male old age grumpiness. He looks at the at the rest of his colleagues with an insufferable air of intellectual superiority, and believes he hasn't been recognized to the extent that he deserves, yet the movie hints he is a bit of a fraud himself, his main claim to fame is having been thanked in a footnote in a book by a famous Talmudic authority. The more successful Uriel (Lior Ashkenazi, who usually plays young macho men, but here plays a middle aged academic against type) is the son. The film lampoons Uriel for being a lightweight scholar and for being too attracted to the media spotlight, yet he seems to be the more psychologically rounded of the two. The tense relationship between father and son finally comes to a bitter confrontation when the elder Shkolnik is mistakenly awarded an important academic prize that was meant for the son (I'm not going to reveal anything else about the plot).I'm also obviously not going to reveal the ending but it seems underwhelming and unrealized, as if the director Joseph Cedar didn't knew how to end the movie. Thus, what was a fine film until then ends in a curiously unsatisfying way. Nevertheless, this is a fine movie with many great scenes. I especially liked two scenes: one is set in a small but tightly packed conference room and ends when one academic shoves another to the wall. In the second scene, a very pretty female journalist goes to the home of the elder Shkolnik to interview him and manages to get him to say very nasty things about his son.

dromasca

If 'Footnote' will win the Oscar for the Best Foreign language film it will certainly by more than a footnote in the history of Israeli cinema, it will be a big event, the first time an Israeli film gets the Oscar. It's just that I do not believe that this will happen (and of course I wish to be wrong), and I also believe that out of the four Israeli films that made it in the final selection of the category in the last five years Footnore is maybe the one that deserves less, as it is simply not as good as the previous three, including director Joseph Cedar's own Beaufort.Just to make clear, Footnote is not a bad film and it has its moments of real beauty. Many of these turn around the letters of the Hebrew alphabet, the words and their meanings, the buildings block of the language and of the Jewish wisdom, and of the sacred text of the Bible. This is probably one of the elements that fascinated the jury of the Academia and made them decide to shortlist the film and include it in the prestigious final selection for the Oscar prize. The film is before all the story of the dramatic relationship between a father and a son who are unable to communicate in and within the terms of real life, but they do communicate and understand each other in codes of words. As with the famous (or infamous) Bible codes stories, the letters and words of the Hebrew language hide a story hidden beyond the first layer of perception available to us, the other mortals. But even if we set aside the element of exoticism that is not that striking for the Israeli or Hebrew knowledgeable viewer we are still left with the exquisite acting of the two lead characters (Shlomo Bar-Aba and Lior Ashkenazi), with strong supporting roles from Aliza Rosen and Micah Lewensohn, and with a mix of styles which is sometimes daring like the description of the career of the son using techniques of 'professional' publicity juxtaposed to the restrained way of presenting the work of the father in the style of commentaries on text. It is in the conflict between the world of ideas and the material world, in the lack of acceptance and integration of the character of the father with the universe dominated by the obsession of the security, showing respect not for the essence but to the superficial ceremonies, it is here that lies much of the ideology that motivates the story in the film.Yet at the end I also felt a feeling of dis-satisfaction. Part resulted maybe not directly from the film itself but my own experience of living in Israel, where religious studies are not and exotic element but one of the key pillars at the foundation of the social and cultural life. There is much to be told about this world which is full of wonders and miracles but also of cheating and demagogy. Cedar's film left me with the feeling that while trying to approach the problematic aspects of this field of life, refused to take any position or insert a critical comment beyond the sin face. Then the openness and the life-like ambiguity which in many other films works wonderfully is taken here in my opinion one or several steps too far. We never know whether the research of the father had any real value, we are left in the dark with the roots of the conflict between the father and the head of the prize Israel jury, and a character like the wife and mother could have been better developed. The strong story of the relation between the son and the father and the son's sacrifice which here goes in different direction than usual remains suspended. 'Footnote' looks well polished but unfinished.