Alex Deleon

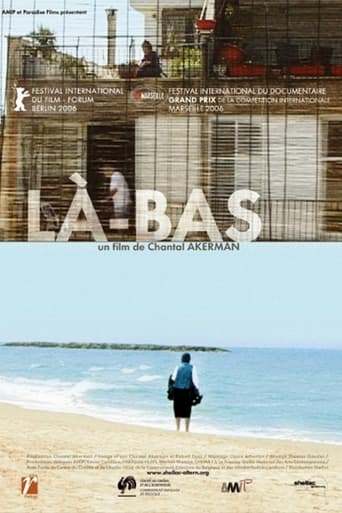

Belgian director Chantal Ackerman was given a tribute an at the 18th Montreal International Documentary Festival. ... La-bàs is a series of long stationary shots out the windows, often showing figures of old people on balconies on the roof or buildings opposite. ... Ackerman in voice-over says she thinks he's watching the plants grow ..."Là-Bas", Chantal Ackerman's Israel Experiment in minimalism is maybe more restful than boring Viewed at the Rouen Nordic film festival, late March 2007. I spent most of my time at the Nordic Panorama -- recent films from 2005 and 2006 -- for me the richest section of the festival. Among the ten films in this section three at least are worthy of special comment, the latest offerings from Chantal Ackerman of Belgium, Aki Kaurismaki of Finland, and Paul Verhoeven, working back in Holland again after a 20 year "leave of absence" in Hollywood.Ackerman's Belgian entry "LA-BAS" ("There" or "In that place") can only be described as experimental -- with a captital X. Being of Jewish origin she was offered funds to make a film in Israel but could think of no appropriate theme or story. So, in the absence of a story, she set her camera up in a dark Tel aviv apartment and just let it run observing some people on the balcony of a building across the way in still life through half-drawn venetian blinds Some motionless sequences devoid of sound except for barely heard street noises run for as much as ten minutes -- an eternity on screen. An unseen narrator (the director herself?) occasionally answers the phone in French, and on one occasion in Hebrew -- apologizing for her deficiencies in the local lingo. We finally get out of the huis- clos for a few minutes on the beach toward the end. I would call this 78 minute film 'restful' rather than boring -- at any rate it isn't as boring as Andy Warhol's infamous eight hour motionless study of the Empire state Building. If not exactly one for the multiplexes it should at least offer great riches to Film Quarterly semioticians.

Chris Knipp

The Belgian filmmaker spent a period of time, unspecified, a week or two, in an apartment in Tel Aviv that was lent to her. She lived there alone, in virtually complete isolation, indirectly filming and narrating the experience, sustained only by "provisions" found in the kitchen, especially rice and carrots, having had stomach trouble from an Israeli salad; didn't go to cafes or supermarkets, and rarely even went out, except for a couple of forays to the sea; the apartment was a block or so from the beach.La-bàs is a series of long stationary shots out the windows, often showing figures of old people on balconies on the roof or buildings opposite. A woman, immobile, is tended to by her husband. One man sits for long periods motionless. Ackerman in voice-over says she thinks he's watching his plants grow. "But I don't think plants grow any faster in Israel," she says.Is this any better than the proverbial watching paint dry? Two aspects, visual and auditory, save this thin, dry, austere documentary from being a sterile art piece and make it both thought-provoking and haunting, for those who have the patience to sit through it; many will not.To begin with, screens filter the light of the windows in a beautiful way: the shots are often handsome, not unworthy of something by Hou Hsiau-hsien or Tsai Ming-liang, if without their human figures moving about.Further, Ackerman's voice overs, spoken off-camera during the shots, though skimpy, provide fleetingly penetrating, brutally frank self-revelations and contexts that range from the personal to the universal. Her father was once going to emigrate to Israal just after WWII and was waiting in Marseille to go, but he was warned that the Palestine environment was too harsh. The family settled in Belgium instead. She speaks of an aunt who committed suicide. Is she herself depressed? She speaks of passivity and laziness. She may be agoraphobic. She clearly is going through an agoraphobic period. She may also be afraid of bombs. A parent calls and expresses concern about her going out to dangerous places; she promises she won't. She speaks of prisons, external and self-imposed: this is one of the latter kind.People call and invite her out. She says she can't because she's working. This devotion to the enterprise makes something positive and substantial, even noble, about this otherwise evanescent, uncertain project. This is an act of painfully heightened self-consciousness, a self-examination, a journal both Zen-like and intensive. She also speaks of reading; making extensive notes; having "complex" thoughts. A certain ambivalence toward her Jewishness is also involved. Finally, with minimal means, Ackerman has forged something unique.A telling image: a Chasidic family leaving the beach. The man, in his quaint outfit, symbolizes the oddity of the Israeli enterprise. Ackerman doesn't comment on the oppression of Palestinians or Israeli dependence on the US. Her seclusion in the middle of Israel's largest city may be comment enough. This is something she apparently can't be a part of. But in her alienation, she couldn't be more Jewish.(Paris, November 2006.)