Andrew Boone

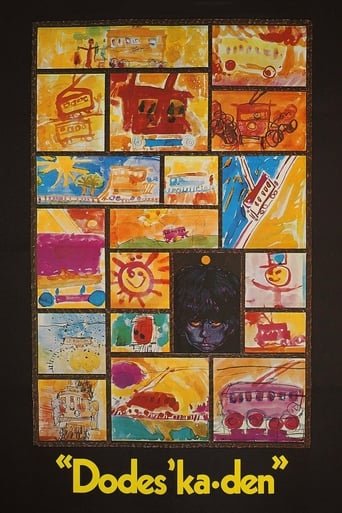

Kurosawa's best films often had a combination of warmth, which is present in essentially every film he ever made, and bleakness, which seems to pop up only every two or three films, as if Kurosawa were prone to depressive spells. This unique blend of moods can be found in "The Idiot", "Drunken Angel", "The Lower Depths", and again here, in "Dodes'ka-den", a heartfelt examination of human misery, which, like all Kurosawa films, lacks the intellectual and artistic mastery of many of his contemporaries, but also possesses a warm humanism that very few filmmakers have ever been able to achieve.Released in 1970, "Dodes'ka-den" (the quirky title is explained in the film's first sequence) saw Kurosawa at a critical juncture in his career. Entering Japanese cinema later than his classical Japanese contemporaries (i.e. Ozu, Mizoguchi, Naruse), but before the Japanese New Wave crowd that would follow (i.e. Suzuki, Imamura, Teshigahara, Ôshima), Kurosawa occupied a unique place in Japanese cinema. His films were very western in both style and content, and they broke from the more traditional values of Japanese filmmaking.Prior to "Dodes'ka-den", Kurosawa was able to get by with a profoundly felt film once every four years or so, while filling out the in-between years with exercises in shallower classicism usually based in the chanbara (samurai) genre of Japanese cinema. Strangely, these latter films — "Seven Samurai", "The Hidden Fortess", "Yojimbo", "Sanjuro" — were often championed the same as the others. Granted, they were effective, sometimes wonderful exercises in entertainment, but they tended to lack both the vision and the thematic depth that marked his best films.For that reason, I was delighted to see "Dodes'ka-den" be the type of film it was: simultaneously despairing and humanistic, since I didn't really know what to expect from this one. Kurosawa himself had remarked, after his last film, "Red Beard" (1965), that he felt he had reached the end of a certain creative cycle, and that whatever happen from that point forward, it would be different. It certainly was. Television had become an increasingly dominant aspect of Japanese culture, diluting the devotion of Kurosawa's previously loyal fan base, and Kurosawa himself seemed to be entering a kind of artistic down-cycle. The rise in popularity of television meant Japanese producers were making less and less money, and were therefore less and less willing to take risks on artistically innovative films. In 1966, Kurosawa's long-term contract with Toho expired, and a troublesome detour through Hollywood ensued. Kurosawa and David Lean were set to direct the Japanese and American sequences, respectively, of the 1970 film "Tora! Tora! Tora!", but neither man ended up directing a single shot for the film. Ultimately, this failed undertaking, along with a series of other issues in Kurosawa's professional life (his broken relationship with longtime collaborator and screenwriter Ryûzô Kikushima; exposed corruption within Kurosawa's production company), sent Kurosawa's career into a downward spiral from which it appeared he might never recover. Indeed, the next decade was a dark one for Kurosawa. He was desperate to make another film, but was struggling. Then something happened that has become one of my favorite off-screen moments in cinematic history. Three of Japan's most famous filmmakers — Masaki Kobayashi, Keisuke Kinoshita, and Kon Ichikawa — came to Kurosawa's rescue, and the four of them formed a production company called the Club of the Four Knights, to whom the concept for "Dodes'ka- den" is credited during the opening titles of the film. The idea was for each of the four filmmakers to direct one film each, but this never happened, and it has been said that true motivation for the formation of the company was to support Kurosawa and help a titan of Japanese cinema to get back on his feet again. It was a beautiful gesture, one too uncommon in the often dog-eat-dog world that is the film industry.Unfortunately, it didn't pan out. "Dodes'ka-den" had a small degree of critical success, but was a box office failure. The film lost money, and in 1971 Kurosawa attempted suicide by cutting his wrists and throat. Fortunately, he survived, and a few years later he was approached by the famous Soviet film studio, Mosfilm, to make a Russian film. That film, "Dersu Uzala", which I've not yet seen, was moderately successful both financially and critically, beginning Kurosawa's recovery as a filmmaker. Still unable to find financing for a new project in Japan, though, he was assisted by none other than George Lucas, a massive Kurosawa fan, in making his next film, "Kagemusha" (1980), for which both Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola were producers. It was the first of Kurosawa's final five films, a period during which he regained his status as a master filmmaker. As for "Dodes'ka-den", Kurosawa's despair is palpable throughout, but so is his warmth and compassion for humanity. It was Kurosawa's first color film, and the color palette is quite beautiful. The film isn't successful at every turn, but it is on the whole. It has very little plot, meandering back and forth between the various inhabitants of what is closer to a trash heap than a town (maybe a small step up from the setting of "The Lower Depths", which is the film I'd say "Dodes'ka-den" has the most in common with). Some viewers, hopelessly addicted to plot and story, might find fault in this, but I wouldn't share that criticism. I felt that the film's drifting plot line gave "Dodes'ka-den" its greatest strength: a narrative that, like its characters, wanders from place to place in search of meaning and happiness, and, like its characters, having not found it, settles down here, in this den of hardship and human suffering, where goodness and sorrow exist side-by-side, unconcealed by the pretensions of a "regular" society that may be less impoverished, but is also less honest, and, for Kurosawa, ultimately less human.RATING: 8.00 out of 10 stars

rad1001

Kurasawa said that this film is about the heart. IMHO, most people are unequipped to understand the film because they lack experience in thinking from a Buddhist perspective. This film begins with several minutes of chanting Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo which is the mantra of all Nichiren Buddhists. We chant Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo because that is the primary method that we use to practice Buddhism. The practice is somewhat like praying and somewhat like meditation, but it is different too, especially because it is very high-charged. Nichiren Buddhists have found that this practice helps our lives in many unexpected ways. The words literally mean "Praise to the great law of the universe" that Shakyamuni Buddha expounded in The Lotus Sutra. Nichiren urged people to chant Nam-Myo-Renge-Kyo to develop their own Buddha nature and, cooperatively, to bring about world peace.Nichiren Buddhists understand that chanting Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo is a tool which each person can use to awaken their inner Buddha nature and experience energy, purpose and a joyful life. The reference to the children throwing things at "the trolley freak" could easily be taken as a direct reference to "Bodisatva Never Disparaging," an important legendary figure in Nichiren Buddhism.I saw this film many years ago when I knew about Nichiren Buddhism but was not actively practicing. The movie haunted me for three decades. I wanted to see it again but was unable to find the title. I finally watched it again last night. I watched it with two questions in mind. My first question was about the man who ran the imaginary(?) trolley. It seems to me that he is representative of all Nichiren Buddhists in that he uses his practice of chanting to draw on a continuous supply of energy from his deepest inner resources. There were other references to Buddhism that could easily be missed. One was the parallel between the man who tricked the would-be suicide into believing he took poison and the parable of the wise potions maker from the Lotus Sutra, who tricked his children into believing that he was dead in order to shock them into their senses. The wise man's statement at the end of that scene, when he said that there is a remedy for every poison, is an obvious statement of the Buddhist principle, "Hendoku Iyaku," which means "turning poison into elixir."Commentators who should know have suggested that the trolley character represented Kurasawa. This should be no surprise. Kurasawa was demonstrating his own determination to keep going despite the near end of his film-making career after Tora Tora Tora. People who chant Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo know what it is like to vigorously chant your way through your problems. Daisaku Ikeda, Honorary President of the Soka Gakai, the worldwide lay organization of Nichiren Buddhists, says that the rhythm of chanting Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo, (which is a very physical practice), is like galloping on a horse. That is not a far stretch from the clickety clack of a train. In fact, I believe that the name of the film is actually a substitution for the phrase Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo.The other question I had on reviewing the film was whether the characters in the story are based on the psychological states of mind known in Buddhism as "ten thousand worlds in a solitary moment of existence" (Ichinen Sanzen). A simplified version of this is the ten worlds, consisting, in ascending order, of hell, hunger, anger, animality, tranquility, rapture, learning, absorption, Bodisatva (the state of caring more for the good of others than for the good of yourself) and Buddahood or enlightenment. According to Nichiren, most people in this despoiled age, known as the "latter day of the law," spend most of their time bouncing around in the lower four worlds and occasionally experiencing life in the fifth and sixth worlds. In the movie, it is obvious that several characters are living in a psychological state of hell. Many others are dominated by hunger, anger and the animalistic instinct to fear those who are more powerful and to pray on the weak. We all possess these potentialities but some learn how to cultivate states that are known as "the higher worlds." Two characters clearly exhibit this: the wise man who seemed to protect all the people in the shanty town and the Buddha-like character who loved and raised the children that his wife bore from other men. The trolley driver was enigmatic but he was also the most self-assured and perhaps the happiest person in the story.Why did he pray for his mother to become smarter? Because if she became smarter, she would not be as bothered by little things that have no consequence, such as all the stupid people who made fun of him because, to them, his trolley was invisible.This film is an allegory. It is about hidden meanings. I cannot say what was in Kurasawa's heart when he made this movie, but to me, it is a very clear affirmation of the optimistic message of Nichiren Buddhism. I would still like to know whether Kurasawa practiced Nichiren Buddhism. With such American cultural luminaries as Herbie Hancock and Tina Turner practicing Nichiren Buddhism, it would not surprise me if Kurasawa used this popular spiritual practice at some point in his life too.

Dustin Fox

Kurosawa, fresh into color, losses sight of his usual themes of truth and perception of reality and opts for a depressing take on Tokyo's slums. Kurosawa stretches for a style that was, in my opinion, his antithesis- that is to say, I feel as if Kurosawa wanted to make an Ozu picture. Poorly paced, poorly conceived, this movie is a rare dud in this auteur body of excellent work. While Ikiru, while being mundane and depressing, was still interesting and well paced, and while Stray Dog depicted the slums and social poverty of Japan without being too heavy handed or boring, do desu ka den has all the somberness that one could expect with its content, with none of the redeeming qualities of earlier Kurosawa pictures.Be warned, this is not a movie that Kurosawa should be judged by.