Rijndri

Load of rubbish!!

Bob

This is one of the best movies I’ve seen in a very long time. You have to go and see this on the big screen.

Billy Ollie

Through painfully honest and emotional moments, the movie becomes irresistibly relatable

Martin Bradley

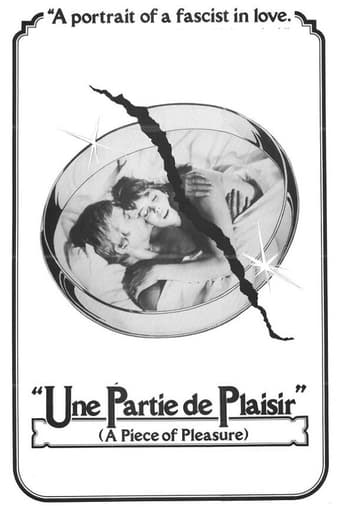

In the cinema of Claude Chabrol the bourgeoisie are distinctly lacking in charm, discreet or otherwise and none more so than Phillipe and Esther, the well-to-do couple at the centre of UNE PARTIE DE PLAISIR, who, at Phillipe's insistence, decide to have an open marriage but when Esther looks like she's falling for the first guy she sleeps with, Phillipe gets very jealous indeed.The territory is, of course, typically Chabrolian but what makes this movie interesting as well as creepy and finally very unpleasant is that it would appear to explore the disintegrating marriage of its stars Paul Gegauff and Daniele Gegauff. Paul wrote the film in what appears to be a kind of exorcism though neither 'actor' rises above the one-dimensional. Nevertheless, Chabrol definitely embraces them treating them with more respect than either of them deserves. It may fit perfectly into Chabrol's world view of things but it's still a pretty hateful movie.

Red-Barracuda

The Pleasure Party was made during Claude Chabrol's strongest period, where he made most of his best films. Unfortunately, however, this is a lesser effort from the great man even if it does share some similarities with his best work. It's a marriage drama about a couple who have a conversation one night where the husband admits past infidelities and goes on to actively encourage his faithful wife to pursue other sexual relationships, allowing for them to have an open marriage. This they do but it backfires on him as he gets increasingly jealous of his wife's affairs.The subject of infidelity is one that Chabrol covered many times in his films and here is no different. Similar to other works, the way the characters deal with news of extramarital affairs here is with not much more than a Gallic shrug, which always seems somewhat unrealistic. But then I suspect Chabrol was never purely going for realism and these infidelities were really a springboard to examine other psychological things. I think the single most differentiating factor comparing The Pleasure Party to other similarly themed Chabrol films is that the storyline and central character are very unpleasant indeed. Paul Gégauff, who also wrote this thing based on his own experiences, plays a version of himself and his unfortunate wife is also played by his real wife of the time, Danièle Gégauff. I really hope that this was not really a true representation of himself as the husband character in this one was a real low-life. Interestingly, several years later Gégauff was actually murdered by a later wife, so it does make you wonder I have to say…Offsetting the highly unsympathetic central character and unpleasant storyline is a typical Chabrol pastel colour scheme and a classical music soundtrack; both of which contrast quite noticeably with the content of the story. By the end of the film I have to admit wondering just what the message was and who we were being asked to sympathise with. An odd film but not one you would rush back to very quickly.

hasosch

I had to press the return function of the remote control when I believed to hear that Paul Gégauff, main actor and writer of the novel which is the base of Chabrols "Une partie de plaisir", says about his wife: "She sides with Korzybski who claims to refuse Aristote, but she hasn't read either one". I heard right. Although I had mentioned polycontextural logic in a couple of my comments, I would have never expected to find it actually in a film - and here we are.If you reject Aristotelian logic, you give up the whole fundamental of our thinking. With the logical categories of position and negation, also the corresponding ethical categories good and bad are abolished. In such a world everything has to be defined newly, and most things are not anymore either good or bad, but both good and bad or neither one for which a term has still to be invented. I have no idea how Gégauff came to the idea to introduce the founder of General Semantics, Alfred Korzybski, in this movie. However, one could imagine that Korzybski's most important mathematical feature, the "multi-ordinality", is seen here as the metaphysical principle of the open marriage structure of the couple which finally leads into one of the most brutal catastrophes ever seen in a movie. The concept of multi-ordinality replaces unambiguous mappings through ambiguous ones - yet, not in a chaotic, but exactly restricted sense. Possibly, in the eyes of Gégauff's character, his wife breaks out of this restricted area when she goes into a sexual relationship with Habib. Gégauff's character says clearly: "Earlier, she preferred sublime culture, and now she is wallowing in the mud of human scum". (By the way: Also the highly sophisticated language which Gégauff's character uses in order to damn every lower level of human existence into hell, shows a philosophical background which is hard to find anymore.) Thus, his wife crossed the border restricted by the Korzybski-functions and is to be condemned because of that. Up to this moment, Gégauff's character still appears as the guardian of a consistently valid metaphysics; e.g., to his future new wife he underlines many times that he feels freed and relaxed. So, the real breaking-point in the story of this movie is there, where Gégauff himself abandons his own metaphysical principles. From his unreachable position, he comes so-to-say down and turns into a vulgar stalker and beggar who is ashamed about himself. However, the story seems to trespass another border, too, namely the border between Gégauff's character and Gégauff, the writer, himself. In the movie he (almost?) kills his wife on a cemetery, in his real live (just a few years after the movie) he was stabbed to death by his second wife, on Christmas' Eve. Therefore, the final question arises: Does the reflexivity which arises when somebody plays himself still belong to Korzybski's principle or does it violate this principle, because self-reflexivity is excluded in a multi-ordinal world?'- It is.

christopher-underwood

Phew! Well, this is certainly no bundle of fun. What an ugly film, was my first thought as I stared at the closing credits. As a seasoned film fan, one is always put on guard when a male lead tells his partner that she should experiment with sleeping with other people. He would not be jealous - oh yea! But here things go from bad to really awful and as someone else has noted it is almost inconceivable that one would be likely to choose to revisit this little number. Having said all that, to discover than long time Chabrol script writer, Paul Gegauff, not only wrote this nasty piece but plays the male lead in question. Not only that but his real life wife plays the appallingly treated partner AND that their actual daughter, plays their screen daughter, just about the only light relief this movie has. Hard to recommend to non Chabrol fans but certainly a powerful piece of cinema.